By Nigel Westmaas

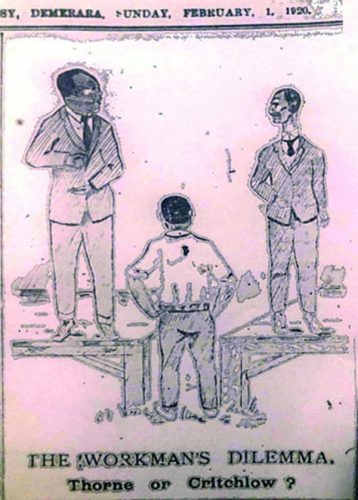

Described as the “lean man with the jerky gait”, Alfred Athiel Thorne straddled the political and social life of Guyana for more than 60 years, in a career spanning from the late 19th to mid-20th century. Yet little is known in modern times about this titanic figure in the political and social life in colonial Guyana and his significant roles in supporting and struggling on behalf of the working class and other causes. Contrast this with the reception accorded his contemporary, Hubert Critchlow, whose career and contributions are fairly well documented and recognized. This is surprising as Thorne arguably had an equally impactful career as his sometime rival Critchlow.

Thorne was born in 1871 in Barbados. He earned the island scholarship in 1890, which allowed him to go to the island’s famed Codrington College. Fortuitously, the College was affiliated to Durham University in the UK, where Thorne studied and received his BA and Masters degrees, and was accorded the unconfirmed status of “the first person of African descent globally to have earned two degrees conferred by a British University.”

A visionary educator, Thorne established Middle School (grammar school) when he arrived in Guyana in 1894 and devoted his life to the cause of education in the colony. The Middle School was an exceptional institution and its students performed very well, contradicting the notion that only the big schools like Queens could churn out students of talent. The Middle School began with 19 students and quickly rose to over 200.

Labour

Thorne was involved in the early labour struggles and trade union organisation and was an active member in Critchlow’s British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU). The initial conflict between Critchlow and Thorne was exposed in contestations of leadership in the 1920s, and the two frequently clashed over issues of corruption, power roles, money, and disagreements on union tactics. Thorne was in fact part of a committee that charged, among other things, that Critchlow had acted like an “autocrat” in his union leadership. There were also counterattacks on Thorne from Critchlow to the effect that he (Thorne), with opportunistic intent, “wanted to be sent to England at a fee to look after the registration of the Labour Union.”

Thorne later founded and became President of the British Guiana Workers League (BGWL) from 1931. The union represented sugar factory workers, municipal workers, nurses and other categories. Dr. Jung Bahadur Singh, politician and labour leader, served as senior vice Presi-dent of the union. One of the objects of the BGWL was to “promote the political, social and economic emancipation of the people and more particularly of those who depend directly upon their own exertions by hand or by brain for the means of life in British Guiana.”

When the Trades Union Council was established in 1941, Thorne was its first President and Critchlow Vice-President. Twenty years after their initial rivalry in the BGLU, Thorne and Critchlow were once again at the top of the trade union pinnacle, seemingly this time, with more amity of purpose. When the Caribbean Labour Congress was birthed in 1945, Thorne was elected vice President of the organisation.

Thorne’s journalism career lasted practically his whole life and included roles as columnist with the titles of “Junius Junior” and “Demos”, plus a brief stint as lead writer of the African Guyanese owned Echo newspaper in the late 19th century. He also published articles for the famed Timehri journal, and was a prodigious and prolix letter writer to all the major colonial newspapers.

Thorne even made international legal news with his celebrated libel case against the local Daily Argosy newspaper. The background to the libel arose from Thorne’s visit in 1904 to the US, where he penned an article for the Boston Trans-cript on British Guiana. The article’s content on the sugar industry in Guyana prompted criticism in the pages of the Argosy. This led to a libel action by Thorne for the sum of $5,000 against the newspaper and a clash in court with another political behemoth of the time, barrister at law Patrick Dargan. Dargan, a friend of Thorne, was a vigorous legal eagle in representing the interests of the newspaper and cross examined Thorne for four days, which “combined to put the case among the celebrated judicial trials” in Guyana. Thorne eventually won and was awarded $500 in damages.

Thorne, with his record of activism across so many spheres and disciplines, was bound to encounter or invite controversy. One newspaper editorial also ventilated on Thorne’s “perpetually moving tongue” and his “strikingly fierce pugilistic gestures.”

The famously blunt Thorne, who could rub his contemporaries raw, was described by some critics as self-centred. Ashton Chase records that Thorne was “nicknamed “Oi Oi” for his frequent references to his own accomplishments.” Chase did not go that far but the expression “Oi Oi” could easily be construed as a “Bajan” accent.

Politics

It was Thorne’s political career that superseded his other skills in a long duree of fifty years of activity in the country’s politics. Thorne was credited with a mastery of constitutional issues, of being an adept diagnostician of colonial issues in the Legislative Council, and as extremely knowledgeable in his grasp of labour problems, education, religion and other matters. Thorne was a strong supporter of the disestablishment movement against the institutional control of mainstream churches in the colony. He “shouldered through the Combined Court a motion for the appointment of a committee to devise schemes for the final disestablishment of the Churches and to allocate the money saved to the establishment of a University College in British Guiana.”

His indefatigable routine required encounters and negotiations with Gover-nors, contestations with colleagues and opponents, and crafting ideas. Thorne was a member of the Georgetown Town Council for an astounding 47 years and, through urban legend and public acknowledgement, was an “electrifying speaker.”

He was active in one of the colony’s highest political organs, the Combined Court, and served as Financial Represen-tative of the North West district from 1906-1911 and 6 years for New Amster-dam. This political acumen and dedication stemmed partly from his activism in the Reform Association, which he had joined on arriving in the colony in the 1890s.

In 1907, Thorne moved a motion in the Legislature targeting the Georgetown Public Hospital and addressing the “cruelty to poor patients, criminal undernourishment, pagan surgical indifference to the underprivileged, immorality of doctors and nurses, high mortality rate among patients, general incompetence of the hospital staff, and diabolical oppression of nurses unenthralled by sexual communism.” He also piloted in the Legislature a motion requesting the British Secretary of State to “elevate Guyana to the Rank of a First Class colony.”

With these feisty and weighty political representations at many levels, and especially on behalf of the poor, it was not a surprise that PH Daly considered Thorne as possessing a “natural socialist endowment” and even compared him to the Fabian socialist Sydney Webb.

But this presumed accolade has to be tempered by Thorne’s pacts with, and concessions to, various governors. Ultimately, the Colonial state would only concede so much, and Thorne and others at times had to make do with Realpolitik manouevres within the system. This political procedure, factoring in the power of the colonial state, resembles Walter Rodney’s description of “resistance and accommodation.”

While Thorne held a general reputation for working across race in the colony, he nonetheless faced moments of controversy or disagreement with Indian Guyanese representatives. One such case was the debate over the Indian Colonization scheme of 1919. In Baytoram Ramharack’s book on Jung Bahadur Singh, Thorne is described as considering the Scheme “injurious to African interests”, and voicing “fears that the introduction of labourers of any favored race at the expense of others would be undesirable and dangerous.” A letter writer in 1916 with the moniker “East Indian” attacked Thorne’s views on Indians, alleging they were “Machiavelli like” in their “attempt to impugn the loyalty of the East Indians of British Guiana”. This was a reference to Thorne’s published remark: “we have heard how loyal the East Indians are to the Crown. Let us look a little more closely into these people of India. Half a dozen or more years ago, India was a hot-bed of sedition and even anarchy.” In response, the “East Indian” asked for the relevance of Thorne’s India reference. “Now sir”, he enquired of Thorne, “in the name of all that is reasonable, what has the political state of affairs of India some six or more years ago to do with the present loyalty of the East Indians of British Guiana?”

The issue of Thorne’s relationship to Indian Guyanese returns in an extract in Clem Seecharan’s Tiger in the Stars. Seecharan highlights Thorne’s support for Governor Collett in 1921 on the issue of Indian rice farmers protesting the Governor’s policy of “cheap rice.” Thorne also succumbed to stereotypes of Indian Guyanese. Referencing their “very scant clothing”, living on “rice and dholl chiefly” while contributing “very little per head to the customs revenues of the colony.” In the same passage, Thorne also let slip stereotypes of African Guyanese, namely that they “live like British people, feed themselves well, and too often over dress.”

In spite of disagreements over issues like the Colonization Scheme and others concerns, Thorne appeared to maintain amicable relations with Indian Guyanese leaders and organisations. In the 1930s Thorne was now overtly predisposed to working unity with the Indian Guyanese community. This was reflected in a meeting held in Grove in 1933, one of his campaigns for the Demerara River constituency in the Legislative Council where Thorne displayed his long experience, ability and potential reach into ethnic and ideological enclaves. A Daily Chronicle report said attendance at the meeting in Grove “was very large and the East Indian section of the district turned out in goodly numbers.” Among his supporters was his longtime colleague Dr Jung Bahadur Singh, who invited the Grove crowd to “consider Mr Thorne capable, as they all knew the keen interest he took in the welfare of the working classes.” The doctor also addressed the gathering in Hindi and was “accorded a great ovation at the end of the address.” Hubert Critchlow, once a rival and critic, also “strongly supported” Thorne’s candidacy stating that the people deserved a voice of Labour on the Council. One of the speakers even spelt out what he said was an “interesting acrostic” of Thorne’s name by supporters of his campaign:

T – Trade

H – Husbandry

O – Opening up the country

R – Roads

N – Negroes

E – East Indians

Thorne recognised the wider dimensions of race and racism and he was very invested and concerned about the “Negro problem”, even at the international level. His article “The Negro and His Descendants in British Guiana”, published in British heiress and activist Nancy Cunard’s prominent 1934 book, Negro: An Anthology, became much sought after as a global transcript of African life in Guyana along with his call call for black unity in the colony.

After the First World War, when representatives of black organisations from the USA attended the 1919 Peace conference in Paris, Thorne lamented the absence of black representatives from the British colonial world, including Guyana. The British government had in effect refused visas or passports to its denizens to attend the conference. The African-American civil rights activist and historian WEB Du Bois had attended the peace Conference as a representative of the NAACP, but their ideas met with a chilly Eurocentric reception. However, Du Bois and other attendees labeled the concurrent 1919 Pan-African Conference a success for bringing the interests of Africa and Africans to the fore. But this was the context of Thorne’s complaint. He felt that in British Guiana there was little evidence of British justice. The British Negro, he admonished, “had never had the opportunity that the American Negro had. The American negro rubbed shoulder to shoulder with the Europeans: the leading men in the United States met with the leading men of other countries and so they knew each other’s needs.”

While his life and work were restricted to, and preoccupied with, Guyana, Thorne would still wax patriotic for his country of birth. Once, when a critic wrote disparaging remarks about Barbados, Thorne immediately pushed back, delineating the progress Barbados had made in the areas of democracy, land reform and general social relations.

He was still active politically at least up the late 1940s and was part of a delegation to London in 1949 to discuss the long-term prospects for West Indian sugar. Thorne was likewise an early proponent of the Federation for the West Indies.

Thorne passed away in 1956. He left a remarkable level of service across multiple disciplines. His contribution to Guyana’s constitutional, educational, political and civic development was immense, and attempting to fill out the narrative or biography of his overall contribution would be an enormous challenge.

Nigel Westmaas is an Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Hamilton College in the United States.