By Jerry Haar

Guyanese highly value education, and that bodes well as the country seeks to capitalise on its oil and gas largesse and finally build the nation that all Guyanese have hoped for since independence in 1970.

An encouraging development along these lines is the recent announcement that the government will offer 20,000 online scholarships to prepare Guyanese for the energy sector among others. The training is intended to be very practical, tied to industry, and aimed at local human capital development, since petroleum-related jobs are presently staffed by foreigners. Scholarship recipients have a choice of more than 80 programmes offered via GOAL (Guyana Online Academy of Learning), including the University of the West Indies.

This pronouncement by the vice president comes in the wake of discussions with ExxonMobil regarding the establishment of training facilities in Guyana. One should hope that other energy companies engaged with Guyana such as BP, Total, Hess, Shell, and CNOOC, also come forward and support human capital development in the country, whether it be for their specific industrial sector or others.

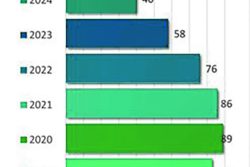

The latest projections from the World Bank indicate that the oil sector is expected to create 3,850 direct jobs and 23,100 indirect ones by 2025, employing 0.7 and 3.9 per cent of the workforce, respectively. While the government is keen on ensuring significant local content, the job-creating potential of the oil sector is limited by its capital- and skill-intensive nature; and Guyana’s small and undiversified manufacturing base is not capable of producing many of the specific inputs the sector requires.

At present the nation’s workforce skills profile and labour market structure are poorly aligned with the needs of the oil sector. As the World Bank has ascertained: “Workers with technical skills that can be employed in the oil sector are currently engaged in construction, transportation, and agro-processing, which are closely linked to agriculture.”

For Guyana, the human capital and workforce development challenge is three-fold. First, provide the local human resources – at all levels – required for a productive, efficient and high-quality oil and gas sector. Second, do the very same for non-energy sectors where Guyana has the potential to compete in global as well as regional markets. However, one should note that there is the risk of pulling away high skilled human capital from other important sectors before training can catch up. Third, provide the educational infrastructure – primary, secondary, tertiary, and vocational-technical – for the skill development required for a competitive 21st -century workforce.

The relationship between education and increased levels of economic growth in non-resource sectors of oil-based economies has been well-documented. Cullen Hendrix, a nonresident senior fellow of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and the author of one such study adds, however, that much depends on the policymaking environment.

So how might Guyana position itself in non-resource sectors to take advantage of the huge economic growth trajectory it is destined to enjoy? Obviously, the nation needs to ride the wave of higher value-added service industries such as business process outsourcing, IT and software, design, and communications/media. Hospitality and tourism, renewable energy and the commercialisation of agriculture and natural resources also have great potential; and even light manufacturing, such as wood-based home accessories, providing small producers can form a cooperative to produce the volume and scale necessary to compete effectively.

The blessing of oil also comes with a curse – namely, the invariable overreliance on that commodity for economic growth. Countries such as Algeria, Iraq, Kuwait, Libya and Venezuela, rely on fuel for 90 per cent of their exports. (Guyana’s neighbour, Venezuela – a failed state, has derived 88-92 per cent of their export revenue from oil, whether the barrel price was $35 or $135.) However, there are exceptions. The United Arab Emirates, Oman, and Qatar, lead the way in industry diversification, as Oman exports vehicle parts; the United Arab Emirates exports or reexports gold, diamonds, machinery, equipment, and electrical appliances; and Qatar with steel, fertiliser, and tourism.

Guyana’s future could be a bright one, but it will require a robust, transparent and results-oriented infrastructure development programme and a system of efficient and effective public administration and business-friendly tax and regulatory policies to spur business attraction, retention and expansion, along with a dependable and strong finance and banking sector. Unfortunately, progress to date has not been impressive. According to the latest World Bank Doing Business report, Guyana ranks 134 out of 190 countries worldwide and in the Caribbean behind Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and Barbados. So, there’s much work to be done.

The challenge of human capital and economic development in Guyana cannot be met and overcome by money alone. It will require individual, cooperative, and collaborative dedication and effort by the public and private sectors and civil society. As one Guyanese business owner and activist declared: “You have to respect what money and success give you, then have the responsibility that goes with that.” For Guyana, at this moment in history, it starts with responsibility.

Jerry Haar is a professor of international business at Florida International University and a Global Fellow of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C.