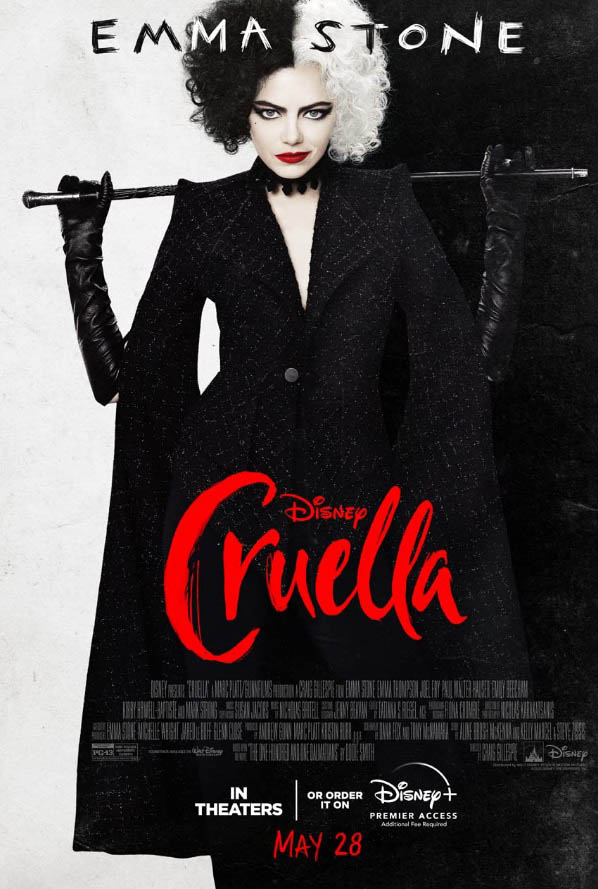

![]() “Cruella”, like many recent Disney live-action films, does not exist on its own – it’s signalling to the past and to the future in a kind of never-ending state of prolepsis. This new film is an origin story of the infamous Cruella de Vil, villainess of “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”. It is a live-action response to a pre-existing Disney animated venture, although technically we’ve already seen a live-action “Cruella” in 1996 with the live-action adaptation of the original tale.

“Cruella”, like many recent Disney live-action films, does not exist on its own – it’s signalling to the past and to the future in a kind of never-ending state of prolepsis. This new film is an origin story of the infamous Cruella de Vil, villainess of “One Hundred and One Dalmatians”. It is a live-action response to a pre-existing Disney animated venture, although technically we’ve already seen a live-action “Cruella” in 1996 with the live-action adaptation of the original tale.

Over the last decade and a half, Disney has been focused on turning their existing animated texts in live-action works – whether remakes of their original animated works, or fleshed-out backstories of existing characters. “Cruella”, like “Maleficent” before it, is of the latter kind. An origin-tale, Craig Gillespie’s new film is a tale of how Cruella came to be, affording her an interiority and informing us that our initial perceptions of her as evil – in the animated film – was wrong.

“Cruella” opens like a bildungsroman – with birth that prepares us for an eventual coming-of-age. A girl is held up for scrutiny, with a head of black and white hair. This is Estella. She is immediately a creature of unusualness. Despite a doting mother, who encourages her to abandon her cruel alter-ego (bid Cruella goodbye, she insists) Estella’s life soon turns tragic when her mother dies and she is left an orphan in London with a resentment for a specific trio of dalmatians. But that part is not quite central to the set-up of the film, not yet. The important bit, for the first half, is Disney-origin tale by way of “The Devil Wears Prada” as Estella struggles to break into the fashion world. Orphaned in London, and with two fellow orphans – Jasper and Horace – as her only friends, she struggles to make her big break in the fashion world.

A chance disaster as a cleaner finds her catching the eye of The Baroness (Emma Thompson), a condescending, but successful, designer who takes her under her wing. The tutelage is cut short when a chance moment with the Baroness becomes key to unlocking Estella’s tragic past and unleashing her stronger – more exacting Cruella alter-ego – she sets to right the wrongs of her past and embrace the cruelty necessary revenge on The Baroness. Don’t worry, though, she doesn’t get too cruel, though. Remember, this is an origin story to explain away the evil, or Disney consumerism as rehabilitation praxis.

It’s an origin-story, a notable part of fantasy work – whether superheroes, or villains – and the question of “how” is what they typically answer, except the question of Disney’s interest in digging into the past of their peripheral villainous characters has always been intriguing. What for? When the trailer for the film premiered months ago, the proto-feminist undertones felt bizarre for a famed puppy-killer – “Cruella” is perhaps less explicitly a feminist tale, but it is one that seeks to rewrite our knowledge of Cruella, explaining away her sharp edges, inviting us to sympathise, understand and root for. But why?

In the lead-up to its release, audiences, and critics have asked: ‘Who is this for?’ The PG-13 film, and recent press, insists this is for young adults and teens. A careless and irreverent take on a character we thought we knew. But who exactly is clamouring to tell this tale? The perfunctory storytelling of the filmmakers cannot quite answer us. Sure, all the trappings of investment is there – money spent on gorgeous costuming, money spent on a soundtrack of notable songs. But little in the way of earnestness or true inspiration. More than the question of whom “Cruella” is for is the question of what “Cruella” is for. Why bother to put out this story, and about this villain?

Screenwriters Dana Fox and Tony McNamara feel confined by the constant referencing and tropes that the film seems to include, not as necessities but as requirements. Dalmatians as key figure of childhood tragedy? Check. A Roger and Anita character to tie us to the original stories? Check. A Dickensian coming-of-age trope to reflect our London story? Check. And so on. It makes sense that this all feels packed to the brim – Aline Brosh McKenna, Kelly Marcel, and Steve Zissis receive additional story credit. More than the stuffiness, though, the scriptwriters seem terrified of making Cruella too evil. They keep reflexively bending backwards to explain away each moment of cruelty and pettiness. Cruella is not an anti-heroine, she is a heroine. The existence of it feels like such a random exercise in rehabilitation, as if to instruct us that if we dig far back enough even the most ostensibly evil figure has a reason for the evil and some justification.

Disney positions itself with a framework that establishes its creative output as products emanating from the Disney brand. That’s not a good, or bad, thing. It just is. The relationship between art and commerce has endured for millennia. But, it’s important to consider how the audience – or in this case the consumer – is meant to respond to this. A New York Times interview with Emma Stone reminded audiences that, for the Disney brand, smoking was a no-go. Cruella’s legendary cigarette is absent. The Disney-brand would not allow it. It seemed almost facetious. How quaint, and yet I found the revelation instructive in its way. For all the forced casualness of the storytelling, this is a work that emerges from a specific brand with a specific intention – certain things aren’t allowed, this is a curated vision of a character for our consumption. But to what end?

There’s a moment in the story that recontextualises the question in a way that fascinated me. Late in the film, Cruella escapes a potentially fateful disaster and appears in the shop of a friend. He gives her a report of an evil act she is claimed to have done. “You didn’t!” he asks aghast. She demurs. And then smiles. “I didn’t,” she admits. “But people do need a villain to believe in, so I’m happy to fit the bill.” Of course.

Evil doesn’t really exist here, at least not for Cruella. She’s just been set up that way, she is filling the role of villainess in our minds because that is expected of her. People feel good to have a villain to root against, but if we go far back enough, we’ll find that the evil was never there. It’s all a matter of perspective. Except, people don’t need villains to exist. They exist without us doing that. There is evil in the world, evil that is not reflexively explained away or justified or originating from some perfunctory story. Sometimes evil just is.

The lines are saying one thing, but the film itself is saying another. The messaging is muddled in the way the diegesis of the film itself addresses its own perfunctorily evil villainess. I wonder if in half a century Disney will reflexively look within itself to explain away that force of evil. And why? It’s an ouroboros-like obsession with itself that feels exhausting. Instead of just making the autonomous story for teens that the film’s press insists that “Cruella” is meant to be, Disney must tie it into something pre-existing. They can’t let go of their own past. And it’s within the film itself, insisting that Cruella cannot move on until she goes back to the past.

But that insistence on relitigating the past belies a startling lack of self-awareness, both for the character and the film itself. The obsession with reflexivity is a distraction because it never comes with actual reflection, not for Cruella, or “Cruella” or Disney. So, Cruella finds a truth that explains who she is like an easily solvable possible. There is no autonomy, only slavish dependence on referred aspects of the past that it expects us to pick up on. It does not need to do the work of being emotive, or feminist, or moving. It merely sets up the cards, and we can read from it what we wish.

Cruella cries from the past to explain what she’s turned into. But, it’s hard to feel empathetic about something that, by design, invites us to read whatever we want of ourselves on to it. It’s a canny sleight of hand, it reads us while we read it. But, what the flourish of the trick is obscuring is that at the centre of this reflexivity is nothing really. We’re reading all of this on to an illusion. It’s eye-catching, but it’s all so incredibly empty. Sure, Cruella is no longer a villainess. And how delightful it is to believe in the goodness of others. Cruella is now a well-intentioned villain trying to solve the puzzle of her past. And by turning her unrepentant evil into something explainable, “Cruella” becomes tiresome and hollow.