By Nigel Westmaas

“Haiti has repeatedly been punished for its original sin of racial insurgency”

-Johnhenry Gonzalez, Maroon Nation: A History of Revolutionary Haiti

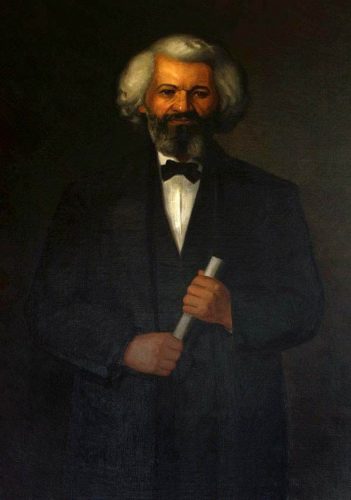

Toussaint Louverture

Haiti’s revolutionary history and the real sources of its perennial failure as a nation state in modern times has too often been denied, sanitized or ignored in general narratives about the country and society. More people are now challenging the pathology about Haiti, that is, the notion that Haiti is poor because it is poor, an impression completely unmoored from Haiti’s significant challenge to the global world system and the penalties that derived from that incipient bravery of declaring a free and independent black republic. Or as Laurent Dubois put it in his book Haiti the Aftershocks of History: “the true causes of Haiti’s poverty and instability are not mysterious, and they have nothing to do with any inherent shortcomings on the part of the Haitians themselves. Rather, Haiti’s present is the product of its history; of the nation’s founding by enslaved people who overthrew their masters and freed themselves; of the hostility that this revolution generated among the colonial powers surrounding the country; and of the intense struggle within Haiti itself to define that freedom and realise its promise.”

At the time of the French revolution of 1789, Haiti, or St Domingue as it was called at the time, was by far the richest colony in the Western hemisphere if not the world. Sugar, coffee, cotton, indigo, and cocoa were among the range of global commodities produced on over 8,000 plantations on the French “owned” island. But sugar was the gold standard of products.

There were 800 sugar plantations on the island. At the time Haiti produced a staggering one half of all the sugar and coffee that was consumed in the Americas and Europe.

There were also about 2,000 coffee plantations, 700 cotton, and 3,000 indigo plantations. To give an example of the economic significance of St Domingue, in 1789 “some 4,100 ships were registered leaving and entering the colony’s ports.”

St Domingue alone accounted for two-thirds of all French colonial revenues, a sum estimated at 400 million francs in the late 1780s. This vast wealth was undergirded by a cauldron of death sustained by the enslavement of a massive black population of 500,000 on the island alongside 40,000 whites and 30,000 coloreds (mullatoes).

It was, however, inevitable that the profound brutalities and terrible conditions on the island for the enslaved would lead to a large revolt.

REVOLUTIONARY TIDES

In 1791 Boukman Dutty, a Vodou priest and Vodou priestess Cecile Fatiman launched the Haitian revolution via vodou ceremony at a place called Boi Caiman. Not long after the wealthiest slave colony in the western world was subject to a massive uprising as now former slaves attacked and burned plantations and effectively destroyed the physical basis of their collective horror and trauma.

Within days, about 180 plantations were destroyed. Thousands of planters and their families fled St Domingue to elsewhere in the Caribbean and North America. Many bolted to New Orleans and other cities on the US East coast. As a reflection of its own slave society, white solidarity and fear, the US Congress even released funds to assist the wealthy planter refugees.

By 1793 a former enslaved and coachman Toussaint Louverture had risen to prominence in the resistance. Toussaint and others, including Dessalines, Christophe, Rigaud, Moise and Marie Jean Lamartienne, were soon involved in a complex thirteen year war defined by shifting allies and the reality of Realpolitik that eventually led to the defeat of three European armies, the Spanish, English and French.

The French was the most resilient of these European armies. In 1801-1802 Napoleon Bonaparte, in a final effort to subdue the resistant black humanity, dispatched the largest fleet ever sent abroad by France to restore slavery on the island. The head of the fleet was Napoleon’s brother-in-law, General Le Clerc. For a moment, after Toussaint had been captured and deposited in a French jail, it appeared the Haitian revolution would succumb. But the French had Dessalines, who served under Toussaint, to contend with. Jean-Jacque Dessalines, a former field slave with over 300 whip marks permanently etched on his back, was one of Toussaint’s most able commanders and also his most ruthless. Faced with a guerilla army and total war Le Clerc was defeated at the battle of Vertieres and died of yellow fever, another scourge of the French. The last remnant of the French army was gone.

100,000 French troops and 19 generals had fallen on Haitian soil and Napoleon’s “Western Design” in which he conceived of a massive continental project including New Orleans and St Domingue, was over. He packed up his remaining troops and hopes, sold Louisiana to the Americans, and opted to remain in Europe, going on to conquer that continent until his final defeat on the frightful field of Waterloo. The Haitian revolution and the army of the enslaved was his first major military defeat.

IMPACT

In 1804 after a terrible war that claimed many thousands of lives, St Domingue became Haiti, an independent country and Dessalines became its first head of state albeit with a monarchical outlook. The new constitution of 1805 emphasized Haiti’s independence as a black republic with one proviso that stated “no white man of any nation can set foot on this territory with the title of master or property owner and cannot acquire any property in the future”. Dessalines proceeded with agrarian reform while attempting to establish (or re-establish) relations with regional and European powers.

In essence, the Haitian revolution of 1791-1804 was a cataclysmic event for a world system largely defined by slavery, especially in the Caribbean and the Americas, where the effects were extremely profound.

One of the first but little acknowledged impact was of course that the French sale of Louisiana (a land mass much greater than current Louisiana) in 1803, adding almost half of the then territory of the United States. Historians have effectively traced this Louisiana concession to the defeat of Napoleon’s armies by the Haitian enslaved. Even scholars who imply there were other factors involved in the sale of Louisiana acknowledge that Napoleon’s defeat in St Domingue played a significant role in the sale to US President Thomas Jefferson that altered the balance of power in the Western world.

At the outset, the fairly young American republic was confused with how to deal with both the revolt and the Haitian state after 1804. Before the revolution of 1804, the second President of the US, John Adams, gave some tepid, strategic support for Toussaint to hold France in check. For his part, the US Treasury Secretary Alexander Hamilton generally supported Haiti on economic grounds, even pushing against Jefferson’s racist reluctance and called for trade links, which was consistent with his own influence on American foreign policy.

After 1804, Haiti was almost in complete diplomatic and geopolitical isolation from the major powers. But the US and other powerful nation states still traded unofficially with the rebel state and Haiti provided about one third of all the coffee consumed in America. Even without diplomatic recognition, Haiti was America’s fourth biggest trading partner and products traded included coffee, sugar, lumber and indigo. Northern businesses were even irritated by the diplomatic embargo as Haiti used the opportunity to impose a 10% duty on American ships entering Haitian ports.

The almost total destruction of the plantation complex in St Domingue meant that the unintended consequences of the victory of 1804 was that sugar (and other products), for example, shifted production sites by default to Cuba, Louisiana, Brazil, and Jamaica, among other locations..

The example of the Haitian revolution stimulated anti-slavery activity in the Caribbean and Americas. In the United States at least three US slave revolts and conspiracies including Gabriel Prosser 1800; the 1811 Louisiana revolt (the largest US slave revolt) and the abortive Denmark Vesey’s 1822 conspiracy were inspired by the Haitian revolution. In the case of Vesey, his plan conceived of an uprising of a staggering 9,000 slaves with an ultimate plan to destroy Charleston (South Carolina) and sail to Haiti.

The Barbados rebellion (Bussa) of the enslaved in 1816 must have been influenced in one form or the other by the events just about 10 years earlier.

In the case of Guyana, as noted by historian Winston McGowan, Haiti’s impact involved, like everywhere else, the fear of an enslaved rebellion and events in Haiti directly emboldened enslaved Africans in the two colonies. The Haitian revolution also led, by default, to a “significant increase in British capital investments in in Demerara-Essequibo and Berbice” and assisted the Guiana colonies to export more coffee to markets in the region, thereby giving the economies a boost.

Haiti also gave practical assistance to movements against Spanish colonialism – notably to Simon Bolivar. In 1816 arms were provided to Bolivar on the understanding that after victory he would outlaw slavery in the freed republics. Bolivar himself visited Haiti on at least one occasion.

In 1825, France sent an armada to Haiti to intimidate the young, isolated republic and forced then President Jean Pierre Boyer into signing an agreement for Haiti to pay an unprecedented indemnity in exchange for France’s recognition of the country’s independence. Haiti took more than a century to pay off the debt and the economy suffered severely from this gunboat diplomacy of the French. Approximately 80% of Haiti’s national revenue was set aside to pay the French debt, worsened by the US invasion and occupation of Haiti between 1915 and 1934.

Meanwhile America’s repressed black population was inspired by Haiti. Hundreds of petitions were sent to the US Congress by white and black petitioners with supportive signatures by mainly black Americans calling for the recognition of Haiti. Seventy per cent of the supporting signees were women.

Haitian President Jean Pierre Boyer from 1820 had opened up possibilities for freed and manumitted African Americans, and 13,000 emigrated to the island in that decade. The Haitian state paid the passages of refugees, who “desired to expatriate themselves from their ungrateful country”.

A later Haitian President Fabre Geffrard proclaimed that his “ancestors, in taking possession of this marvelous soil, were careful to announce in the constitution that they formed, that all negroes scattered through the West Indian Isles and North and South America belonged, of right, to the Haytien family.”

African Americans in general, and black and white abolitionists before and after the civil war, rejoiced in the presence of an independent black republic in the region. David Walker’s famous Appeal (1829) called Haiti “the glory of the black and the terror of tyrants”.

White abolitionist John Brown’s admiration for Toussaint and the Haitian revolution was also evident and he reportedly knew the revolution’s course and success by heart. He deemed his effort at Harper’s Ferry in Virginia in 1859 in which he and his followers attempted to spur the dismantling of slavery in the US as a “2nd Haitian revolution.” For their part Haitian newspapers extolled Brown’s assault on slavery, and Haitian flags flew at half-mast’ as Haiti “officially mourned his death for three days” while Haitians raised $20,000 for Brown’s family and the other rebels after he was hanged.

The United States, through the instrumentation of Lincoln, finally recognized Haiti in 1862 amid the raging civil war. Celebrated black abolitionist Frederick Douglass called the US recognition of Haiti “a most remarkable development.”

During the US civil war, some black Union army regiments even performed drills copied from Haiti’s revolutionary army. In 1861, another emigration movement from USA to Haiti began and in 1863 approximately 500 black Americans arrived in Haiti.

By the end of the century, the question of diplomatic relations tied to US interests dominated the news cycle between the two countries, with Frederick Douglass featuring prominently.

Douglass, later an emissary and US ambassador to Haiti, had a tough time as a black man negotiating on behalf of an imperial state. There were contradictions in his pursuit of relations with Haiti. On the one hand, he tried to persuade the Haitian state and people to give up their strategic territory like Mole St Nicholas, a sea port in northern Haiti that was important for the American navy and army given its location near the Windward Passage. At the same time, he resented his own government’s imperial and covetous attitude toward Haiti.

Douglass eventually came to realise that Haiti was a nation state that held a dignity of its own in the community of nations. He met frequently with famed Haitian philosopher, journalist, statesman and anti-racist activist Antenor Firmin. It was Firmin who apparently convinced Douglass that America’s imperial moves for St Mole were contrary to the self-determination of the country and to blacks in the USA. In the end, Douglass resigned as US ambassador, stating that he “could not accept imperialism ‘as a foundation upon which I could base my diplomacy.’”

There has been some progress and a plethora of new academic work on Haiti’s powerful impact in the region throwing more light on the anti-systemic and world changing nature of the epic Haitian revolution.

Haiti had its own internal demons. Very few of the governments and leaders engendered after the revolution were democratic. There were coups and authoritarian leaders and impulses right up the present, but the Haitian people have remained rebellious and resilient throughout it all.

It is therefore of critical importance to continue to link the contemporary problems of Haiti to that momentous period in the late 18th century, when the country gave history, and the struggle for human rights and self-determination, a tremendous shove in more ways than one.

Nigel Westmaas is an Associate Professor of Africana Studies at Hamilton College in the United States.