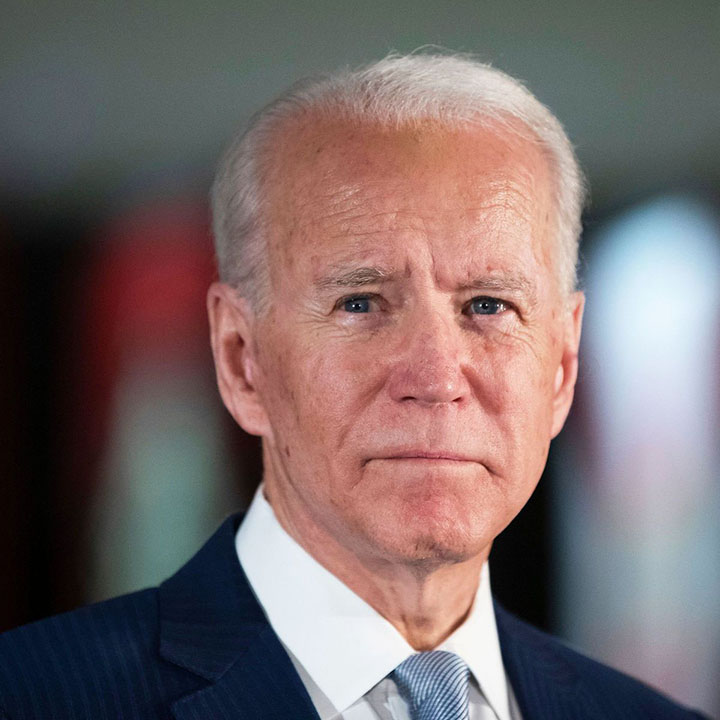

TULSA, Okla., (Reuters) – Joe Biden yesterday became the first sitting U.S. president to visit the site in Tulsa, Oklahoma, where hundreds of Black Americans were massacred by a white mob in 1921, saying the legacy of racist violence and white supremacy still resonates.

“We should know the good, the bad, everything. That’s what great nations do,” he said in a speech to the few survivors of the attack on Tulsa’s Greenwood district and their descendants. “They come to terms with their dark sides. And we’re a great nation.”

Biden said the deadly Jan. 6 attack on the U.S. Capitol and efforts by a number of states to restrict voting were echoes of the same problem.

“What happened in Greenwood was an act of hate and domestic terrorism, with a through-line that exists today,” Biden said.

White residents in Tulsa shot and killed up to 300 Black people on May 31 and June 1, 1921, and burned and looted homes and businesses, devastating a prosperous African-American community after a white woman accused a Black man of assault, an allegation that was never proven.

Insurance companies did not cover the damages and no one was charged for the violence.

Biden said one of the survivors of the attack was reminded of it on Jan. 6 when far-right supporters of then-President Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol while Congress was certifying Biden’s 2020 election win.

The White House announced a set of policy initiatives to counter racial inequality, including plans to invest tens of billions of dollars in communities like Greenwood that suffer from persistent poverty and efforts to combat housing discrimination.

Families of the affected Oklahoma residents have pushed for financial reparations, a measure Biden has only committed to studying further.

Biden said his administration would soon also unveil measures to counter hate crimes and white supremacist violence that he said the intelligence community has concluded is “the most lethal threat to the homeland.”

VOTING RIGHTS

He also entrusted Vice President Kamala Harris, the first Black American and first Asian American to hold that office, to lead his administration’s efforts to counter Republican efforts to restrict voting rights.

Multiple Republican-led states, arguing for a need to bolster election security, have passed or proposed voting restrictions, which Biden and other Democrats say are aimed at making it harder for Black voters to cast ballots.

But Biden nodded to a political reality he believes has stymied his efforts, including “a tie in the Senate, with two members of the Senate who vote more with my Republican friends,” an apparent reference to Democratic Senators Kyrsten Sinema and Joe Manchin.

Biden oversaw a moment of silence for the Tulsa victims after meeting with three people who lived in Greenwood during the massacre, Viola Fletcher, Hughes Van Ellis and Lessie Benningfield Randle.

Now between the ages of 101 and 107, the survivors asked Congress for “justice” this year and are parties to a lawsuit against state and local officials seeking remedies for the massacre, including a victims’ compensation fund.

Biden did not answer a reporter’s question about whether there should be an official U.S. presidential apology for the killings.

The president “supports a study of reparations, but believes first and foremost the task in front of us is to root out systemic racism,” spokeswoman Karine Jean-Pierre said.

RACIAL RECKONING

The visit came during a racial reckoning in the United States as the country’s white majority shrinks, threats increase from white supremacist groups and the country re-examines its treatment of African Americans after last year’s murder of George Floyd, a Black man, by a white Minneapolis police officer, sparked nationwide protests.

Biden, who won the presidency with critical support from Black voters, made fighting racial inequality a key platform of his 2020 campaign and has done the same since taking office. He met last week with members of Floyd’s family on the anniversary of his death and is pushing for passage of a police reform bill that bears Floyd’s name.

Yet Biden’s history on issues of race is complex. He came under fire during the 2020 campaign for opposition to school busing programs in the 1970s that helped integrate American schools. Biden sponsored a 1994 crime bill that civil rights experts say contributed to a rise in mass incarceration and defended his work with two Southern segregationist senators during his days in the U.S. Senate.

His trip on Tuesday offered a sharp contrast to a year ago, when Trump, a Republican who criticized Black Lives Matter and other racial justice movements, planned a political rally in Tulsa on June 19, the “Juneteenth” anniversary that celebrates the end of U.S. slavery in 1865. The rally was postponed after criticism.

Public awareness about the killings in Tulsa, which were not taught in history classes or reported by newspapers for decades, has grown in recent years.

“It is necessary that we share with each generation the past and the significant imperfection of inequality,” said Frances Jordan-Rakestraw, executive director of the Greenwood Cultural Center, a museum about the massacre visited by Biden.