Those European nations which participated in the slave trade have in recent years become more sensitised to their past. Here in Guyana we sometimes forget that the period of slavery in this country lasted for well over a century and a half under the Dutch, and just over forty years in the case of the British. This is not to say that the Dutch transported large numbers of Africans here and the British very few; quite the reverse in fact. The local plantation operations for most of the period of Dutch rule were very small-scale in comparison with colonies such as neighbouring Suriname and the English islands, and so the demand for labour was modest in consequence. In the decade before they abolished the slave trade between 1796 and 1806, the British brought in huge numbers of enslaved Africans to work on a vastly expanded plantation system.

(The slave trade here was abolished by Order in Council a year before the Act of Parliament brought it to an end in most other colonies. This was because this country, along with one or two others was a Crown Colony, after having been taken during the Napoleonic wars.)

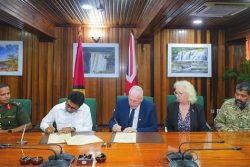

A few years ago the National Archives of the Netherlands restored and digitised the local Dutch documents in our archives, at a cost of €400,000 paid for by the Government of the Netherlands. The three-phase project also included training on the preservation of paper. Records relating to Guyana’s history under the Dutch are found not just locally, of course, but more especially in the National Archives in the Hague, as well as its British counterpart in Kew, London. Why they are in these two overseas institutions instead of just one, is not really known. It is the British in 1814 who decided to take some Guyanese documents in Holland to London, while leaving others in situ. There seemed to be no rhyme or reason as to how they split them.

Whatever the case, it is fortunate that they have been preserved, because those in Guyana have been subject to great attrition over the years. They have been stored inadequately, eaten by bookworm and cockroaches, not to mention all the other enterprising vermin who frequent these shores; burnt deliberately and accidentally; destroyed by floods; and simply left to moulder into oblivion. The Netherlands project was therefore a saviour for those which remained.

But the records in London, the Hague and Georgetown are not the sum total of what obtains in relation to the Dutch colonial period in this country. Among other places there is the Zeeland Archives in Middelburg, the Nether-lands. (Zeeland is a province of the Netherlands.) They are of interest to us because they hold the records of the Middelburg Commercial Com-pany, which was involved in slave-trading, and transported enslaved Africans to Suriname, St Eustatius and Curaçao, but where this country was concerned, to Berbice especially. In the 18th century they forcibly moved 31,000 Africans across the Atlantic. In total the Dutch transported 600,000 enslaved Africans between the 16th and the 19th centuries.

According to the Zeeland Archives, while human trafficking has been carefully recorded in the MCC documents, there is much which we are not told because it is essentially a financial record of trade. Accounting, therefore, is its main function, and the humans who endured such suffering in the process remain anonymous, with their birthplaces, ages and family connections unknown. For all of that there is a great deal of information on how they were bought and sold, and what life was like on board, including details relating to episodes of resistance.

The Zeeland Archives say that the MCC records constitute the world’s most comprehensive collection on human trafficking in the 18th century, documenting 114 slave voyages, and as such they are unique. In 2011 they were placed on UNESCO’s Memory of the World Register, which is the World Heritage Site for documentary works. In addition, the Archives has digitised the collection, and has made a website about the voyage of the ship Unity from 1761-63. Whether it came to Berbice during that period is not stated on the Zeeland Archives news site.

And now, with the greater consciousness among the slave-trading nations about their past, as mentioned above, the Archives has collaborated in a six-part TV series on the Dutch transatlantic slave trade and Zeeland’s role in it. All the episodes can also be seen online, although it will be a challenge for those who have no command of Dutch. The series on television began on May 27, but the episode which is to be shown on June 17 might be of particular interest to us, since it deals with arrival in South America. There is an extra seventh episode which can only be viewed on YouTube and which deals with resistance on board the vessel Vigilantie.

While it is important for the Dutch themselves to become acquainted with their colonial past, and discover their long sojourn in this country which the overwhelming majority of them have no knowledge of, it is also important for the new generation of Guyanese historians to explore it too. For this, however, they must acquire a mastery of the Dutch language. It is only by that route that they will get a more detailed idea of the barbaric journeys to which their forebears were subjected, and be able to access the story of the Netherlands’ around 170 years of colonial rule here. If they do not do so, a huge portion of their history will be closed to them. In the meantime Dutch historians, newly alerted by the various sensitisation campaigns, will be writing it for them.