One question that was unanswered in the series of columns on the government’s overdraft at the BoG pertains to inflation. The four columns from April to May of this year did not touch the topic of inflation, even though they were discussing the issue of financing government spending with money instead of debt.

Since the government is able to “create money out of thin air” when it spends from its account at the central bank, why was there no severe inflation? It is an interesting question to ask given that we are taught that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon”. It turns out that inflation is a complicated matter and money creation is not always associated with instantaneous increase in the prices of consumer items such as rent, rice, mini bus fee, phone bill and many others. Inflation is always measured as a percentage change. Specifically, it captures the percentage rate of growth of “all” prices in the economy. The most popular measure of the level of all prices is the consumer price index.

As long as the price level is increasing or growing, inflation is always present. There are a few instances when the reverse happens and prices fall in the aggregate – an unwelcome phenomenon known as deflation. Inflation is a natural outcome in any economy. Inflation becomes a problem when it is no longer predictable. A stable and predictable rate of inflation is usually a good thing for an economy.

As long as the price level is increasing or growing, inflation is always present. There are a few instances when the reverse happens and prices fall in the aggregate – an unwelcome phenomenon known as deflation. Inflation is a natural outcome in any economy. Inflation becomes a problem when it is no longer predictable. A stable and predictable rate of inflation is usually a good thing for an economy.

In general, when some observers invoke the statement “too much money chasing too few goods” they are worried about unexpected inflation. If inflation is predictable, we can always take actions such as using price and wage contracts to control spending and budgeting. The worst form of inflation is known as hyperinflation – the type they are having over the western border in Venezuela. We don’t ever want to reach the stage of hyperinflation because it destabilizes the monetary system and makes it difficult to conduct business, not to mention the serious harm to poor people.

When the central government spends from its BoG account it injects money into the economy. This does not happen, however, when the government makes payments out of the system of accounts known as the Consolidated Fund, unless some of the sub-accounts are quarantined at the central bank. This aspect of money that is created from government spending is known as the monetary base.

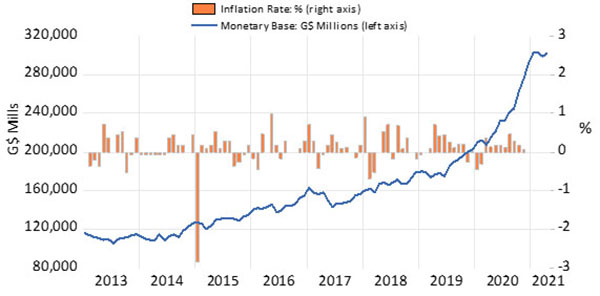

The left axis of the line graph above shows base money. The graph shows data from Jan: 2013 to April: 2021. The base money supply was at its lowest point of G$105.2 billion as at July 2013. It reached a peak of around G$303 billion in January 2021. The money supply flattened from January to April 2021.

The rate of inflation is expressed in percentage terms and is shown by the bar charts (right axis). Each bar shows a monthly rate of inflation. Unfortunately, I could not find inflation data after November 2020. However, we have enough data points to make a conclusion. It is clear that the inflation rate was quite stable from January 2013 to November 2020. By stability, I mean the percentage growth does not explode as we would see under hyperinflation. Instead, it bounces around or reverts to a number around 0.1% per month. The lowest inflation was negative 2.8% in January 2015. The highest monthly inflation rate of 1% occurred in May 2016.

The predictably stable monthly inflation occurred as the money supply was growing at a much faster rate. Therefore, we can conclude, that in the case of Guyana – just as in the United States after massive quantitative easing from 2008 – the connection between money supply and inflation is weak and statistically insignificant (I calculated the statistical significance).

Before I discuss why this relationship is insignificant in Guyana, a word on the flatlining of the monetary base from February 2021. This occurred because the government has switched from money financing to debt financing. As was reported in the press recently, the government increased the domestic debt ceiling. This means that the BoG will expand its sale of Treasury bills on behalf of the government. The monies raised will be deposited into the Consolidated Fund and some will probably balance the BoG account.

The T-bill sales will allow central government to make future payments, which the BoG mops up again by another round of T-bill sales, and so on. A few years ago, there was a lot of talk of a slush fund used by the pre-2015 PPP/C government. What is colloquially called a slush fund is really a well-established system of Treasury-central bank coordination. This is not necessarily a bad thing, but there is need for substantial reforms to streamline the monetary and Treasury accounts in order to prevent some of the excesses and possible corruption I discussed in a previous column on the overdraft. As I have noted in one of the said columns, no payment should be made from the Consolidated Fund which ought only to be the receiver of all government revenues. All government cheques should be written from the BoG account. The Treasury and the BoG will then need to coordinate the accounts to make sure they are never in overdraft. It would greatly enhance transparency and minimize the opportunity for shenanigans.

Although consumer price inflation remained stable, the monetary financing was not without negative consequences. The demand for foreign exchange increased as more money was chasing few foreign currencies. This can be evidenced by a decline in the international reserves of the BoG over the same period as the BoG overdraft. The central bank was forced to sell hard currencies to stabilize the exchange rate. There was also a time when the commercial banks found it hard to satisfy all the demand for foreign exchange.

The shortage of foreign currency is a classic textbook adjustment given excess money injections. For economies like Guyana, the first line of weakness is pressure in the foreign exchange market when there is excessive money in the system. When people have more money, they tend to purchase foreign goods, requiring more hard currencies.

The shortage in foreign exchange means the exchange rate depreciated over the time when there was the overdraft. The street rate at one point reached G$230 to one US$. Some small cambios were selling American dollars for G$220. The commercial banks went up to around G$216. Even the official statistics from the Bank of Guyana show a depreciation.

Some would argue the depreciation should have been much steeper. There are various reasons why the rate did not depreciate to around G$300. One factor has to do with the control of foreign exchange trading by the commercial banks, which now – on average – trade over 97% of all foreign currencies. This high concentration of trades allows the BoG to maintain leverage over the rate by using moral suasion over the banks. Therefore, in the end, the lower selling rate charged by the commercial banks dominated the small cambios and curb side money changers.

While Guyana dodged consumer price inflation since 2013, there are troubling signs in the global scene that it will spill over to Guyana. The BoG is also struggling to hold ample international reserves in spite of the massive investments surrounding the oil sector. The floods present a supply shock that will increase food prices in the coming months.

The next column will discuss the global supply disruptions engendering higher inflation overseas that will spill over into Guyana. The higher oil price will be a double-edged sword for Guyana. We will discuss these themes in a fortnight.

Comments can be sent to: tkhemraj@ncf.edu