Enslaved Africans had been emancipated for less than two years when Richard Schomburgk, a Prussian scientist, arrived in hot and humid equatorial British Guiana on the evening of Friday, January 21, 1840. Upon arrival, he noted that there were “rows of merchant vessels under English and North American flags” in the busy port of Georgetown. The ships brought goods from Europe, the United States, and Canada. They were in Georgetown to load cargoes of the colony’s primary exports—sugar, molasses, and rum—to Europe and North America. Sugar defined British Guiana’s place in the political economy of the Atlantic world during the mid-19th century. The golden-brown crystals from Demerara enjoyed a special place in baking and confectionery in the United States.

Enslaved Africans had been emancipated for less than two years when Richard Schomburgk, a Prussian scientist, arrived in hot and humid equatorial British Guiana on the evening of Friday, January 21, 1840. Upon arrival, he noted that there were “rows of merchant vessels under English and North American flags” in the busy port of Georgetown. The ships brought goods from Europe, the United States, and Canada. They were in Georgetown to load cargoes of the colony’s primary exports—sugar, molasses, and rum—to Europe and North America. Sugar defined British Guiana’s place in the political economy of the Atlantic world during the mid-19th century. The golden-brown crystals from Demerara enjoyed a special place in baking and confectionery in the United States.

Schomburgk had come to British Guiana under a commission from Frederick William IV, the King of Prussia, to study the colony’s flora and fauna. His findings, along with a map of the colony drawn by his brother Sir Robert Schomburgk, were later published in two volumes in Leipzig, Germany in 1847. These volumes were later translated by Walter Roth and published in British Guiana in 1923. The books, which include descriptions of his sojourn in Georgetown while preparing for fieldwork in the hinterland, provide an invaluable snapshot of the social life and administrative practices of British Guiana’s ruling class during the early post-slavery years.

When Schomburgk disembarked from the Cleopatra on the morning of Saturday, January 22, 1840, he soon realized that the city was as busy as the port. He used phrases such as “hurry and hustle” and “hurried and scurried” to describe the pace of commercial life. He mentioned the ice hawkers. British Guiana, like other communities in the colonial tropics, had been importing ice from Canada and the United States for almost three decades at that time. Ice was an important ingredient in the refreshment culture of a hot and humid colony about 5 degrees north of the equator.

Schomburgk also noted that the shops stocked:

“everything that a European accustomed to luxury and high living can possibly wish for. From North America came flour, potatoes, salt fish, salted and smoked beef, and pork, peas, biscuits, cheese, butter, herrings, horses, pigs, ducks, … rice, onions, dried apples and pears, leather, furniture, ironware, and the chief article of import ice.”

Also featured in his list of imports was distilled water.

When Schomburgk arrived in 1840, the changes in the colony’s economic life were evident. As previously mentioned, enslaved Africans had been emancipated less than two years before, and the scheme to import indentured labor to shore up the pivotal sugar industry had already started. Capital was also seeking other opportunities in the colony. The hinterland was there to be harvested, and private investment and settlement were encouraged.

Beginning in the 1820s, interest in gold mining increased. The El Dorado lore, first told by Sir Walter Raleigh in the 17th century, was reignited. British Guiana seemed attractive to Europeans seeking opportunities away from the various crises (war, drought, famine, and a devasting economic recession) that had characterized life for more than a century. The ripples of these crises were felt across the world. Beginning in 1834, European immigration to the colony accelerated. Portuguese indentured laborers started coming to British Guiana in 1834. Schomburgk seemed to be surprised to meet recently arrived Canadian, German, Maltese, and Portuguese immigrants. They were all there to “try their luck.”

When Schomburgk arrived in British Guiana, the colony was in the middle of the 1837–1842 yellow fever epidemic caused by the Aedes aegypti, a mosquito that thrives in stagnant water. Another of the capital city’s problems was access to pure, palatable drinking water. Schomburgk reported that the government brought in “fresh drinking water from distant lying rivers.” At the time of his visit, there were 17 artesian wells in coastal Georgetown. However, because of salinity and the high iron concentration, the water was not “adapted for drinking purposes.” The preferred source for drinking water was rainwater collected in vats and other containers that were breeding grounds for the Aedes aegypti mosquito.

The heat, humidity, and questionable water quality led to the importation of water (mineral and distilled) and fermented beverages. Large quantities of beer, ale, and stout were imported from Europe. During the 19th century, water quality was also a concern across much of urban Europe. Thus, natural spring water was at a premium. Not only were these spring waters mostly palatable, but they were also effervescent. They had fizz, and they were also considered to have medicinal properties. Spring water was expensive, so European working people depended on fermented beverages, such as beer, ale, stout, and cider, to slake their thirst. They were cheaper and safer. Most of the beer, ale, and stout imported to British Guiana from Scotland was packaged in stoneware bottles. The litter from this period is still evident. It is sometimes erroneously described as “Dutch bottles.”

During the summer of 1767, English chemist Joseph Priestley perfected a method to produce “mineral” water. He demonstrated the process for adding carbonic gas to water to create the fizz normally associated with natural mineral water. This ushered in the age of the artificially carbonated beverage. By April 1790, Jean Jacob Schweppe had launched his bottling company in the United Kingdom. The company initially sold carbonated water, and the rest, as we say, is history.

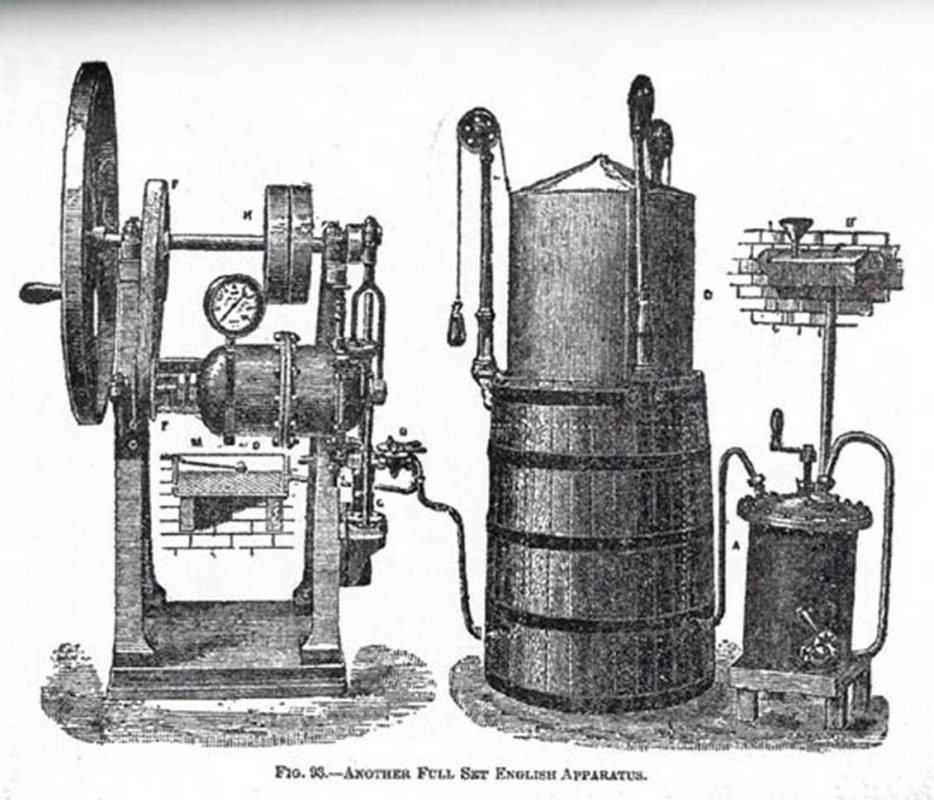

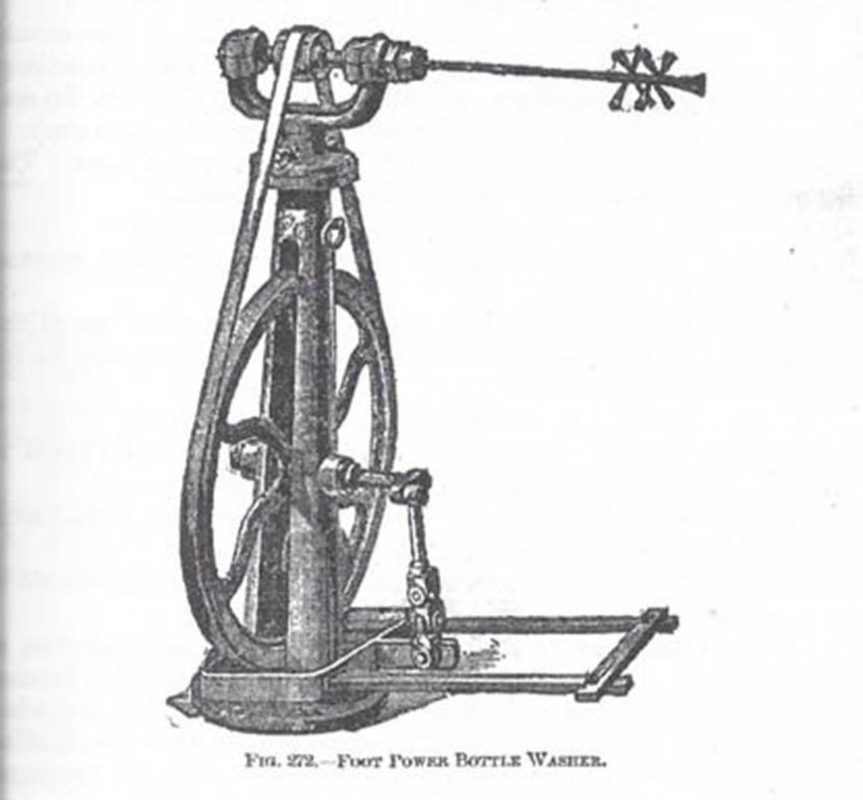

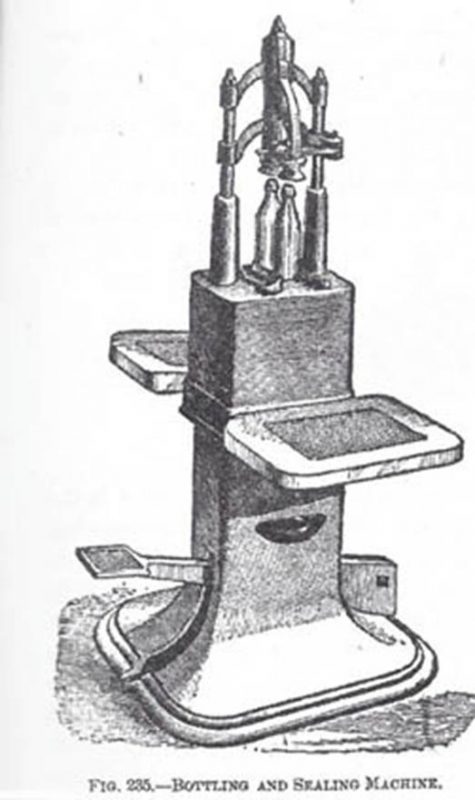

By the early 1800s, a subset of artificial mineral waters, described as “carbonated saccharine beverages” (also considered medicinal), had become popular, and the technology for mass producing them were distributed globally. A leading manufacturer of this technology was Bratby and Hinchliffe in Manchester, England. In time, these technologies came to British Guiana, and a few residents “tried their luck.” The result has been the lively story of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages, “sweet drink,” in the Guyanese experience.

One can comfortably speculate that “sweet drink” bottlers were already operating in British Guiana by the 1870s. The first bottler in Trinidad (c. 1870) is reported to have acquired his Bratby and Hinchcliffe technology through Alexander Russell, a commission agent in Georgetown, Demerara:

Aerated drinks have been made locally [in Trinidad] for a very long time since the 1870s when small carbonation plants made by Bratby and Hinchliffe of Manchester England became available in the Caribbean, being distributed by Alexander Russell of Georgetown, Demerara [now Guyana].

The same source implies that some of the early “sweet drink” entrepreneurs in Trinidad and Tobago might have had prior experience in Demerara:

Not all of the newcomers from Demerara were sugar-specialists. Some, like the Chinese Austin family, settled in Cedros in the far south-western tip of the island around 1890 and began manufacturing carbonated drinks. Indeed, almost the entire soft drink industry in Trinidad, at one time, bought its bottling and aerating equipment from Alexander Russell and Co. in Georgetown. Popular brands like Serra Kola Champagne and McShine’s aerated drinks owed their existence to machines imported from Georgetown.

Describing the early technologies, this Trinidadian source noted, “These were basically small hand-cranked dynamos which infused plain water with carbon dioxide in a swift and cheap manner, costing only £38.”

This Guyana–Trinidad connection was reactivated during the 1990s, when Trinidad’s largest bottler started to distribute its products in Guyana. In the next installment, we will begin the review of the Guyanese bottling experience.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Shahabuddeen, M. From Plantocracy to Nationalisation: A Profile of Sugar in Guyana. Guyana: University of Guyana, 1983.

Roth, W. Translator and Editor. Richard Schomburgk. Travels in British Guiana During the Years 1840 – 1844 Carried out under the Commission of His Majesty the King of Prussia. Together with a Fauna and Flora of Guiana according to the works of Johannes Müller, Ehrenberg, Erichson, Klotzsch, Troschel, Cabanis and others. Including Illustrations and a Map of British Guyana drawn by Sir Robert Schomburgk. Leipzig: J.J. Weber, 1847. Georgetown: Daily Chronicle, 1923.

Bissessarsingh, A. “Sugar and Soda: The Trinidad-Demerara connection in the 19th century.” Downloaded from Facebook page “Angelo Bissessarsingh Virtual Museum of Trinidad and Tobago.” See also “A Designer on an Island.” Accessed at: https://designeronanisland.tumblr.com/post/109537015851/solo-delivery-truck-1964-the-trucks-were-bedford?fbclid=IwAR2nDMFEC6xXQnkRolgI3MQGyfNghwkgCnPJqvNTzpOtCc9SXlpGvHHWG2U

Josiah, B. Migration, Mining, and the African Diaspora: Guyana in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries. New York: Palgrave Press, 2011.

Donovan, T. FIZZ: How Soda Shook Up the World. Chicago: Chicago Review Press, 2013.

Sulz, C. A Treatise On Beverages, Or, The Complete Practical Bottler, Full Instructions For Laboratory Work, With Original Practical Recipes For All Kinds Of Carbonated Drinks, Mineral Waters, Flavorings, Extracts, Syrups, Etc. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald Publishers, 1888.

Raleigh, W. The Discovery of Guiana. Available online at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2272/2272-h/2272-h.htm

Vibert Cambridge is Professor Emeritus, School of Media Arts and Studies, at Ohio University

Vibert Cambridge is Professor Emeritus, School of Media Arts and Studies, at Ohio University