Introduction

Thus far I have introduced two major metrics in order to illustrate my thesis that the noise and nonsense mis-informers in the social and print media have colluded and connived in generating fake misrepresentations and dated dogma (from four decades ago), in order to portray a relentlessly demoralizing, paralyzing and retrogressive economic narrative of Guyana’s coming time of oil and gas production and sale. These two metrics are, firstly, the presentation of the generation of global greenhouse gas emissions, ghg, in petroleum production as if, these were simply the exclusive responsibility of big oil, when, as indicated last week, these transnationals are neither the only nor main culprits.

State-owned national oil companies, NOCs, as a group hold more than three trillion United States dollars in assets and produce more than half of global crude oil presently. The second metric is the fake news mis-specified claim that the Government of Guyana GoG, projected government take is severely limited to the proverbial “crumbs”. Today’s column appraises this second metric further.

Social media have attributed a wide range of motives to those promoting fake news in the echo chambers of Guyana’s oil and gas sector. Astoundingly, such motives range from, on the one hand: naiveté, ignorance and lack of awareness; and on the other: the corrupted pursuit of “benefits“, financial and otherwise. Some even go as far as attributing motives to personal deception, along with purposeful local and international deception, dis-information and diversionary tactics.

Before proceeding further in this environment, I declare upfront that, my partisan interest and motive in this matter is to secure, through data analytics and processed information, the successful navigation of the Petroleum Road Map for Guyana, which I had earlier presented in this Sunday series of columns over an extended period in 2018. Additionally, in the interest of full disclosure, I declare the following: 1) I have never worked for, nor in any manner whatsoever, have I had transactions or provided any services to any big oil or state-owned oil company; and 2) no known family member is or has been an employee or service provider. There is no track record of financial transactions, or having a born-again revelation in regard to oil producers

Setting the economic framework

As an economist writing for the general public I have always found it comforting to use consensus economic formulations when evaluating constructs. Thus, when evaluating Guyana’s Production Sharing Agreement, PSA, previously, I have applied standard energy economics to appraise its fiscal terms. Theoretically two economic sub-disciplines; namely behavioral economics (trade-offs and risk-reward theorems) and institutional economics (principal ̶ agent relations) apply. Given this, the main objectives of the Guyana Authorities, as resource Owner or Principal, should be to: 1) obtain the most “wealth” from its oil and gas resources; and 2) do so through promoting maximum exploration of Guyana’s petroleum resources and their subsequent development. During this process, maintaining the country’s desired levels of national control of upstream value added petroleum activity becomes the third objective.

On the other hand, the objectives of the Agent (Exxon and its partners) are assumed to require: 1) “building equity”, through petroleum “finds”; 2) producing from these finds at the lowest possible cost; and, 3) keeping the compatibility of 1 and 2, with the highest likely profit margin.

For this, energy economics argues standardly that, if the global petroleum sector was sufficiently competitive, one would expect the oil and gas markets to ensure routinely that: 1) countries with unfavourable petroleum resource geology 2) relatively “higher operational costs”, and 3) relatively poor crude quality would have to offer the most favourable fiscal terms in order to encourage investors. And, with the reverse configuration countries would offer the least favourable fiscal terms. Unfortunately, as I have shown repeatedly in this series, the petroleum market is not (competitive) efficient. Such an outcome cannot therefore be left to global “market rules”, as would happen in other businesses.

The above observations logically lead to recognition that market solutions are not available. Worse, the above circumstance generates a fundamental dilemma: “highly competitive global bidding” for rights to explore and develop petroleum resources, cannot be expected to achieve the market objective of matching assessments of petroleum fields/resources to fiscal terms on offer by host governments.

Indeed, to the contrary, the hydrocarbons market is celebrated today for its many imperfections, unknowns and uncertainties. And, these ensure a key defining feature of competitive (efficient) markets ̶ availability of information ̶ is absent from the global hydrocarbons market. As a result, one can safely conclude that, until there is enough information to fuel stiff competition, market outcomes will not determine what can be borne by the Principal and Agent in oil contracts. And, therefore, the most likely profit.

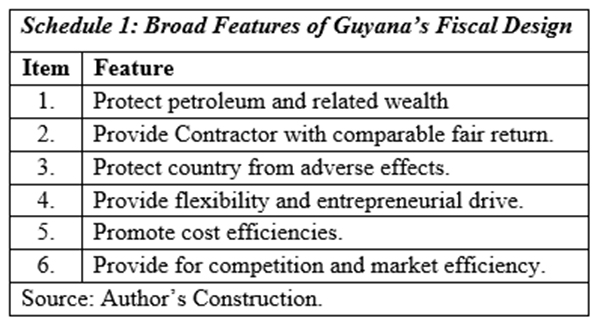

Based on the above description, the key tasks facing the Guyana Authorities (Principal) can be summarized as follows: First, to protect the state’s petroleum and other contingent wealth, both in its natural and improved states. Second, to offer the Contractor (Exxon Mobil and Partners) a fair return to their investments, when compared to similar environments and resource configuration. Third, to protect the country against manipulation, speculation, and the systematic taking of abnormal profits. Fourth, to foster entrepreneurial flexibility for the Contractor (Agent) and promoting organisational and institutional flexibility. Fifth, to encourage and reward cost efficiencies, as allowed by law. And finally, above all, to ensure the Principal is able at all times to promote competition and market efficiency, as the prime drivers of economic outcomes.

Conclusion

The points advanced in the above Section are captured in Schedule 1 below. Next week I relate this discussion to the average effective rate of taxation and the per barrel costs of oil for the five projected operations to 2025/2026 as estimated in the IDB Technical Note, which is the data source of this discussion.