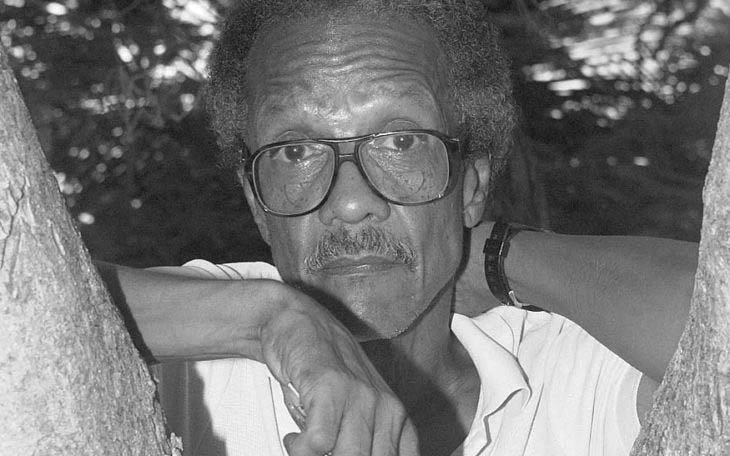

The recent death of one of Guyana’s most acclaimed actors, the legendary Clairmonte Taitt, was marked by a number of tributes and remembrances. They included a biographical sketch in the Stabroek News by fellow actor and director Ken Corsbie and recalled Taitt’s excursions on stage and his family background in Guyana before he moved to Barbados.

The recent death of one of Guyana’s most acclaimed actors, the legendary Clairmonte Taitt, was marked by a number of tributes and remembrances. They included a biographical sketch in the Stabroek News by fellow actor and director Ken Corsbie and recalled Taitt’s excursions on stage and his family background in Guyana before he moved to Barbados.

One of the most important recalled his lead role as James Tyrone in Eugene O’Neill’s Long Day’s Journey Into Night, the dark tale of a house divided, which was not only one of Taitt’s most memorable performances, but an extremely outstanding play in the context of modern drama.

The production was staged by The Theatre Company at the Theatre Guild Playhouse in Georgetown in May, 1989, directed by Ron Robinson, and produced and managed by Gem Madhoo-Nascimento. It was presented in collaboration with the US Embassy in Georgetown in public honour of the 100th birth anniversary of O’Neill, one of America’s greatest playwrights. At the same time it honoured Taitt, who was brought from Barbados to play the role, which turned out to be an award-winning performance in the year’s best production in Guyana.

By that time, Taitt had established himself as a foremost actor and musician in Barbados, continuing a career that started in British Guiana under very privileged conditions. In Long Day’s Journey Into Night, having returned to the place where he learnt theatre and started his career, he played opposite Guyana’s best actress Margaret Lawrence as Mary Tyrone, with the supporting roles of the two sons, Jamie and Edmund, played by Gordon Marshall and Jasper Adams. Maya Trotz completed the cast.

Clairmonte Taitt was a member of the famous family whose home in Georgetown, Woodbine House, was popularly known as Taitt House or Taitt Yard because it was an arts centre. It promoted visual arts, music, theatre and sports. The Taitts were a Renaissance family of track and field athletes and dramatists.

Apart from Clairmonte, the family included Helen Taitt, Guyana’s legendary classical dancer who became a professional in ballet and conducted a school. The house was a venue for performances of drama and dance in the 1950s to 60s, and has today been converted to the Cara Lodge Hotel. Several of Guyana’s most distinguished artists including Michael Gilkes, Corsbie, Stanley Greaves were associated with it and had some learning experience there.

But there was another institution that enlarged and continued the unofficial function earlier assumed by the Taitts’ private residence. That was the Theatre Guild of Guyana, which built its own playhouse in 1962. Although also a private institution, it was more formally established as a theatre for public performances and grew to be a training ground for several of Guyana’s foremost dramatists, many of whom went on to become leading Caribbean personalities. The Guild was known as an exporter of talent.

Taitt, who also became a member of the Guild, was a prominent one of those exports. He continued productions and performances in Barbados. Fellow dramatist Gilkes wrote the play The Last of the Redmen (2006) as a fictional biographical take on the patriarch of the Taitt family. It addressed many aspects of a British Guiana coloured middle class which had become extinct, with the aged Dr Redman as the last survivor giving an interview to a reporter. The name “Redman” is an obvious pun on the West Indian concept of “red men”. The play acknowledged its debt to Samuel Beckett (Krapp’s Last Tape), but also has resonance of Derek Walcott’s Remembrance.

Gilkes wrote the one-man play (a full length drama for a single actor) for Clairmonte to perform. It was, after all, about his family. But the actor declined the demanding role, fearing that he might not remember the lines, and Gilkes performed it himself.

Significantly, it was produced by Madhoo-Nascimento for GEMS Theatre Productions in the very Ballet Room at Cara Lodge, the former Woodbine or Taitt House, where many performances took place when that house flourished. It also played in Barbados and Trinidad.

The close biographical connections between Clairmonte Taitt, his background in Guyanese theatre, and the important place of the 1989 production of Long Day’s Journey Into Night in that theatre, was an echo of parallel connections between O’Neill, his play, and American theatre. The play is autobiographical and dramatises O’Neill’s agonising experience of growing up in a house divided against itself. It tells the tragic story of his own father, mother and elder brother, in a brand of theatre that was the most important in America in the twentieth century. It changed the craft and introduced realism /social realism to the stage in the USA.

O’Neill’s plays, which began to develop after 1912, eventually made their mark on American theatre around 1920. They deepened the drama. There was Shakespeare and some classical drama, but it was previously dominated by melodrama and some vaudeville. They put on stage for the first time on Broadway and around the country plays that examined real life among the people, among the proletariat, the waterfront workers and sailors, prostitutes and social conflicts never seen before on Broadway. The language and style of speech were those of the people on the streets and in the workplace.

Realism had already been spreading in Europe and the UK and it was O’Neil who caused it to develop across the Atlantic. His plays, like The Hairy Ape (1924), did for the USA what TS Eliot did for world poetry in 1922 with The Waste Land. The face of poetry was transformed radically with the introduction of modernist verse and set the tone for the moderns as reflected in Ezra Pound, and taken up by the likes of WB Yeats, WH Auden, E E Cummings, Rabindranauth Tagore and Dylan Thomas. The older styles and fetishes of language were done away with and replaced by a more down to earth language and imagistic forms.

Realism had taken root in Europe with the works of Anton Chekhov, Henrik Ibsen and Strindberg. The plays of O’Neill began to make an impact in the USA where he won four Pulitzer Prizes over the decades while utterly transforming drama. He shaped pathways for such timeless masterpieces as A Streetcar Named Desire by Tennessee Williams, Henry Miller’s Death of A Salesman and Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin In The Sun.

O’Neill was born in the theatre in 1888. Actually in a hotel room in New York because his father was a leading actor who travelled with his family to perform. He grew up in theatre, backstage, in rehearsals and constantly on the move. The family did have a house where they spent time each year, but the show business lifestyle had an impact. His mother was addicted to morphine and his elder brother was an alcoholic.

O’Neill went to boarding schools, left university after just one year of study, went to sea where he spent some time working on ships, then on the waterfront before he returned to university and started writing seriously. His plays became hits and he gradually gained notice and success on Broadway. He rescued himself from an aimless life, but the rough experiences and some Marxism taught him to write about real people and circumstances. His plays were tragic with only one comedy, Ah, Wilderness (1933). But they shook the earth, attracted attention and he was also awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1936.

Long Day’s Journey Into Night (written 1941 but published and performed 1957) is regarded as his best play. The drama takes place throughout one day in the dysfunctional household of James Tyrone, a leading actor, who has made a lot of money, but is a miser. His wife Mary develops an addiction to morphine after she was required to take the drug to relieve pains she experienced owing to the birth of her second son, Edmund, who is ill. The Tyrones’ elder son, Jamie, is an alcoholic.

The family constantly experiences unease, and during the day shown by the play, they argue and blame each other. The play begins in the morning and continues through the long day, ending at night. The three men are drinking, and by the end of the day they are drunk. Mary is taking shots of morphine but while everyone knows about it, she denies it, as if she is not aware, although the effect it has on her is obvious.

Tyrone is blamed for his wife’s condition since he has the money and could get her good medical treatment, but is too stingy. Similarly, his son suffers from inadequate medical care and Tyrone is blamed for being too cheap. Fog gathers outside and engulfs the house, getting thicker as the day progresses. This is symbolic of the state of the family inside and is marked by the gradual decrease in stage lighting inside the house as the family squabble becomes more depressing.

The play confronts dysfunctionality; how deceit, disloyalty, dependency, depressing psychological conditions, addiction build conflict and tax interpersonal relationships, leading to blame and pitting humans against each other. It is the anatomy of a family afflicted by illness and addiction, which are further symbols of the discord and lack of healing human bonding. The playwright presents a symbolic day’s journey and the tragic drama of a house divided.