I’ve spent way too much time marvelling at the oddity of the title of Steve Soderbergh’s new crime drama, “No Sudden Move”. It’s strangely ill-suited for a filmmaker whose film titles tend to be typically evocative, not just in his breakout debut “Sex, Lies, and Videotape” but up to last year with the very precise “Let Them All Talk”. This time around, though, the genericity of “No Sudden Move” seems out of sync with the machinations of the plot in ways that I find perplexing, although considering why the title sounds so familiar, and even generic, might be a window into the film in a roundabout way.

In a heightened moment late in the film that sets us up for a series of double crosses, one character chastises another. ‘You’re not smart enough to know how not smart you are,’ he spits out. ‘Which makes you unpredictable and sloppy.’ Like many things in “No Sudden Move”, the line rolls off with a wave of self-awareness, like a quip, immediately encouraging us to read it in and out of context. It is preternaturally quotable. It’s important that this line is not a damning ironic critique of the movie itself, because little – if anything – in this movie is sloppy. At least not in the sense of being accidental. Soderbergh’s work has always been defined by an incredible focus on working things out, and “No Sudden Move,” in particular, is hardly spontaneous. Instead, it is deliberate and efficient, setting up a Russian nesting dolls sequence of crime within crime within crimes, all existing within a framework with specific socio-political leanings.

In an aesthetically dun 1954 Detroit, recently released convict Curt Goynes is looking to make some quick money to retrieve some land that was stolen from him. A helpful neighbourhood barber tips him off to a potentially prosperous client. The client is Doug Jones, who sets about hiring Goynes and two strangers (Ronald Russo and Charley) to pull off a quick and easy heist at a family home. Russo and Goynes will babysit the mother and her two children, while Charley will tag along to the patriarch’s office to retrieve a document from a safe. Easy work for $7500. Or, maybe not. And a swift mix-up turns leads to the realisation that Goynes is in way over his head. In a moment of heated panic, a murder occurs and from there the plot begins to unravel. And then some.

The documents contain some corporate information that certain powerful men want in their possession. The specificities are peripheral for Goynes, and the other main characters, who are mere cogs in a wheel of capitalism and neoliberalism. What started off as mere document retrieval becomes a sprawling story involving corporate espionage, two mob bosses, at least three adulterous affairs, infiltration of a criminal empire, race relations and class critique. “No Sudden Move” has it all, and it’s coming to us all in swift burst. The small man is trying to make the most out of a losing situation, not realising that they are mere marionettes for those at the top.

It’s a compelling, if familiar, idea of America as corporate rot painted with the sheen of suburban domesticity. But, it does not all come together. Not completely. Soderbergh has mastered the art of insouciance as a tonal aesthetic, but here it feels more off-kilter than instructive. Ed Solomon’s script is working in the register of a Soderbergh venture like “Traffic”, a kind of deliberate societal critique where many moving parts come together to create a tableau of societal rot. But, Soderbergh seems to be working in “Ocean’s Eleven” mode, ambivalent and amiable as we watch some charming lowlifes do their best to stay afloat.

At the film’s end, a final title-card tying it all together with socio-cultural implications feels like part of a different movie. The script seems to want us to believe in the emotions of these people (although Solomon’s insistence on delaying information becomes a liability of its own) but Soderbergh only imagines them as concepts within a larger framework which renders them interesting but not consistently worthy of our investment. It means that “No Sudden Move” goes down very easy, but very little of it really lingers. We don’t really care who dies and/or when. We’re just curious to enjoy the machinations.

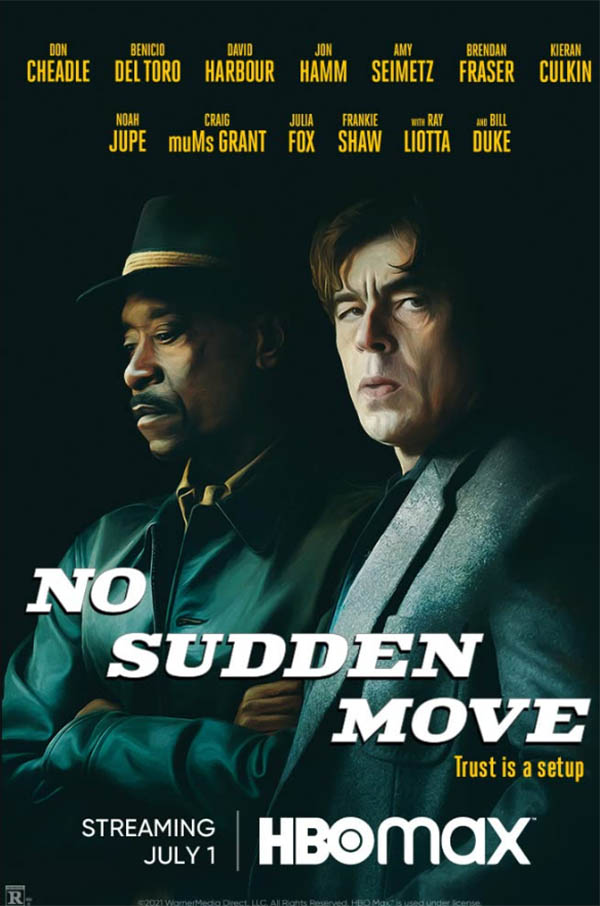

At the centre of the story is Don Cheadle (famously of “Ocean’s Eleven) as Goynes and Benicio Del Toro (famously of “Traffic”) as Russo. The two strangers form a criminal partnership for the ages – or at least a day – as they traipse around Detroit doing their best to get out of a sticky situation. As the plot hurtles around them, Soderbergh excavates their natural chemistry to perform a slightly winking burlesque of traditional noirs with a winking self-awareness. In their strongest moments together (particularly in a sequence where they’re joined by a harried, and excellent Ray Liotta) the film approaches a level of idiosyncratic silliness that feels easy and lithe.

The actors are almost all in good form, some better than others. The Cheadle/Del Toro relationship gives the central dynamic a helpful energy that would not work otherwise. Both actors are playing particularly understated representations of familiar versions of themselves. Cheadle is given the most emotional beats, although here again the script’s attempt to tie him to larger points about structural racism feel too ambivalent to matter. Freed from the plottier aspects, Del Toro is able to play with a more careless suavity to understated but effective results. The film’s best acting weapon, though, is Amy Seimetz as a harried housewife unwittingly taken hostage by the duo. Much of the film becomes a series of sequences tied together by Goynes and Russo, but Seimetz lingers in a way that grounds the first act. There’s a craftiness to the way she uses her body, projecting conflicting emotions of annoyance, fear, anger and mild excitement that complicate the film. She also understands the contours of the film’s not-quite-realistic, but not fully stylised language in a way that injects her moments with energy. It’s an energy the film misses when she leaves, especially because she’s playing her Mary Wertz as a specific woman with very specific foibles rather than as a concept to fulfil a larger theme. When it draws out from Wertz and family to extend to the real world it becomes more effortful. Still pleasurable, but every-so-slightly tedious.

It also does not help that I cannot quite make sense of the visual aesthetic of the film, which is incredibly jarring. The wide-angled lens and off-kilter framings are obviously a deliberate choice, but it feels completely out of place with the world of this story and its intentions. Soderbergh, working under the pseudonym Peter Andrews as cinematographer, is obviously boasting his stylistic abilities but it ends up making the nods to Very Important Issues feel more like a game when the camera itself seems to be mocking the very world in which these characters exist. I can’t say ugly in good conscience, but the visual aesthetic is the least pleasant part of the film. It’s too fond of a brown dunness that ends up feeling incongruous to the own liveliness within.

“No Sudden Move” is never really unpleasant, though – wide-angled brownness notwithstanding. It’s not especially significant or indelible, but it’s also consistently fun. Part of the fun is from the way that you imagine everyone here can do most of what they’re doing here in their sleep. A noir film as a lark. Which is why it’s at its very best when it’s least interested in the bigger picture and playing around with individual arcs of trivialities.

No Sudden Move is currently streaming on HBOMax