A year ago, unsung marine turtle conservationist, Audley James, 80, left the protected area of Shell Beach, Mabaruma Sub-region after 33 years, knowing that the once dwindling population of endangered marine turtles in north western Guyana was on the increase. He is now concerned that hunters in the Moruca Sub-region are again slaughtering the endangered species and peddling their eggs and meat for consumption in spite of the area being in a protected zone.

“Right now in my hometown, Santa Rosa and in other parts of Moruca, people are selling turtle meat. I don’t like that because of the amount of years and effort, I, my immediate family and extended family have put into saving those turtles. The turtle population had gone down very low. When I left Shell Beach a year ago, the population was increasing among the Leatherback, Green, Hawksbill and even the Olive Ridley. As far as I can see, they are now under threat again,” James said.

When asked in a recent interview about his work in conservation, James told Stabroek Weekend he had always had a concern for the conservation of the flora and fauna of this world. He recalled the poisoning of the savannahs, rivers and creeks to harvest fish, thereby killing off the juvenile fish and halting regeneration, by his own Indigenous Peoples. He, himself as a boy, had taken part in these activities.

It was not until he was working in Africa and stationed in the Central African Republic that his awareness of conservation came to the fore.

“I saw what was going on with the slaughter of elephants for their tusks and other endangered wildlife species and the decimation of their populations. It was sad. I vowed that when I came home I would try to do something to save some wildlife or the other.”

By this time he was against the poisoning of the rivers to obtain fish for food and the overharvesting of logs.

He approached then village leaders of Santa Rosa, Albert ‘Bertie’ La Rose and John Atkinson about his concerns. “I talk to them about those things and the consequences but I never got them to see eye to eye with me,” he said.

James was born in Santa Rosa village and grew up with his grandmother, Gregoria Gomez, at Cumuchiri along with his brothers Basil and Donald. He is married to Violet. Together they have seven children, six girls and one boy.

He was educated at Santa Rosa Roman Catholic School and got into mining at an early age as many young men from that hinterland community have done. He worked with the then Interior Department as a miner from 1961 to 1972 in several parts of the country, including Cuyuni, Ekereku, Kamarang, Potaro and Imbaimadai, mainly during the dry season.

He was then recruited as a mining specialist to pass on his skills to miners in the Central African Republic, where he spent five and a half years from 1972.

“After I came back from Africa, I still used to do diving. It was on one of those breaks from diving that I went into turtle conservation,” he related.

“During the 1980s, when I got fed up with not doing much at home, I would go to the beach like others from my area, and kill a few turtles to eat. On one of my trips I met Dr Peter Pritchard at Shell Beach. I asked him what he was doing and he asked me the same thing. He told me he was trying to save the turtles and I was destroying it. He explained the danger of extinction that the marine turtles faced and I understood the importance of conservation. He asked me to work together with him and I needed no persuasion. That was how I started.”

Pritchard was one of the world’s leading experts on the history, biology and conservation of turtles.

A leap of faith

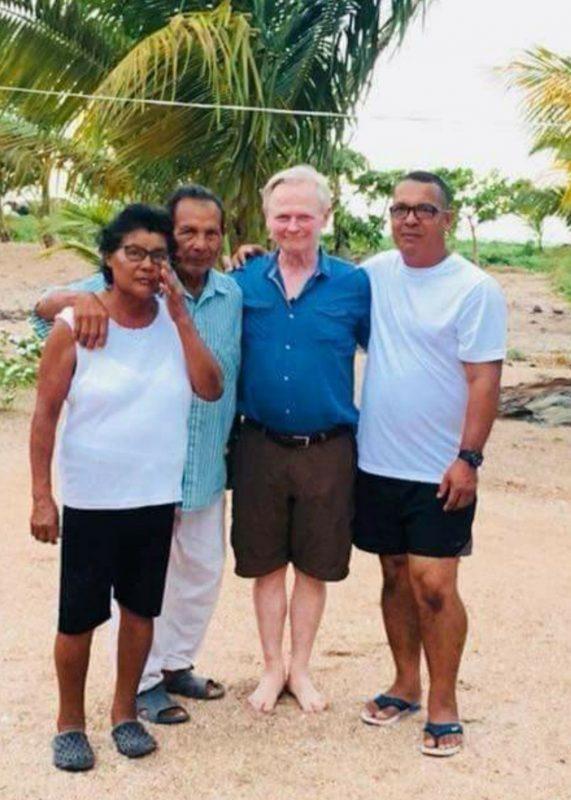

At 48 years, when some his age would be thinking about retirement, James took a leap into the unknown and launched the turtle conservation project in 1988 with his presence on Shell Beach and under Pritchard’s guidance. He enlisted his wife Violet, his son Romeo, his brother Donald, a relative Compton Edmonson and two others not knowing what was in store for them as they braved the rough waves of the Atlantic, the elements and wildlife, including jaguars and swarms of mosquitos. They made Shell Beach their home for over three decades.

“Our biggest problem was finance. At first, we had to go it alone. Violet, Romeo and I pooled together whatever we got to start the project. In 1988, we were just seven of us there. Violet, the only female, was the cook.”

After a time, he said, their numbers increased. Among others, they were joined by three of his nephews, his brother-in-law Theodore Rodrigues and another relative, Marlon La Rose. His daughters often volunteered their services as well.

They began by patrolling the beaches. “Any turtles we found, we measured and tagged… We would make nurseries. When they finished nesting, if they were not in a suitable area, we would place the eggs to hatch in a nursery we had built at the camp and released the hatchlings into the sea. I enjoyed doing it. My wife enjoyed doing it.”

They also tagged a leatherback in 2007 that made regular trips back to Shell Beach. “In 2019 she was tagged in Canada with satellite tracking device and we monitored her for several weeks as she roamed the sea.”

The nesting season ran from March to the end of July.

The first turtle tagged was a Hawksbill on August 5, 1988. She returned at about the very time and date at Almond Beach in 1990, 1992 and 1994, James noted.

Noting that the Leatherback become adults after 10 years, James said in the 2000 season, they had about 4,000 crawls in one season. (Nesting female turtles leave tracks or “crawls” made by their front flippers when they go onto a beach.) Prior to this they would have had four or five crawls at night compared to hundreds they witnessed during the 2000 season. James believes that the thousands that came to nest at Kamwatta were the leatherback hatchlings they had released into the sea in 1990.

The Green takes 25 years to mature, James said, and after 25 years there were numerous Greens in the nesting season from about four or five in a season 25 years earlier. Similarly the number of the Hawksbill grew.

When they started monitoring, they found no Olive Ridley. Eventually they found one crawl and in recent years they had been seeing about eight or nine in a season. The Olive Ridley generally nests on the smaller beaches.

The Leatherback is also known by the Indigenous Peoples in Region One as mata mata, the Green turtle is called bettiya, the Hawksbill is korai and Olive Ridley, kerikai.

When turtle hunters from the villages in Moruca went to the beaches, James said, “We talked and educated them about the need to protect the turtles. If we saw fishing boats drifting, we would go out on the sea to meet the fishermen. We had a lot of cooperation. A few people escaped as carcasses were found on the beach.”

James and the other wardens would spend a week or two or more at different beaches depending on the crawls.

Several beaches make up the stretch of what is known as Shell Beach, starting with Father’s Beach at Moruca Mouth, Iron Punt, Corkwood, Gwennie Beach, Tiger Beach, Luri Beach, Bolton, Kamwatta and Almond Beach, which has washed down further south.

With the assistance of the Guyana Marine Turtle Conservation Society (GMTCS), James said, “We started carrying students from the schools at Santa Rosa, Kwebana, Warapoka, Waramuri and Manawarin to Shell Beach. We had a team from the University of Guyana as well. They helped a great deal in awareness.”

James and the turtle wardens moved from Moruca to Shell Beach on a more permanent basis in 1990. This was two years after they had begun the project. They planted crops including ground provision and coconut and built little houses. They built a primary school, a health centre and a building to accommodate guests.

Once their work started gaining recognition, people started to visit the area to see what they were doing.

“We used to move every two weeks because we focused on other beaches but we had our base camp at Almond Beach. Almond Beach has since eroded. The area where the school and other houses were, have washed away. We moved some of the buildings further down and now I understand that where they were relocated have also been washed away. Coconut trees and other trees that we planted have drifted into the sea. We used to move our lodgings according to how the erosion took place. I have pictures to show what it was like.”

James left Shell Beach a year ago when Almond Beach started to erode and the Protected Areas Commission (PAC) assumed oversight for the area. The shells were pushed by the waves and are now closer to Waini Point where another beach is building up.

James’ son, Romeo, began working at Shell Beach at about 15 years, learning on the job. The duo of father and son have travelled to the United States, Suriname, the Caribbean and other parts of the world and learned international best practices in conservation.

“We learnt a lot from workshops and they learnt a lot from us,” James said.

“Dr Pritchard at the time was connected with Audubon and Greenpeace and they gave us some assistance. After that we got some aid from different organisations, including Conservation International, Audubon Society, UNESCO and a British group. The GMTCS came into being and assisted with seeking funding, providing other forms of assistance and awareness. It was led at one time by Annette Arjoon, Major General Joe Singh and Dr Raquel Thomas.

“In the year 2000, WWF (World Wildlife Fund) came on board to assist. We got some fuel from Shell Antilles. We hadn’t so much problems from 2000.”

Changes

After the PAC took control of Shell Beach as a protected area, James said, “Everything was changed.” He claims that the PAC took in wardens with no experience about the nesting seasons.

“When the PAC went out there, they told me their men were trained. They brought in people from the Rupununi, Berbice and Kaieteur. I want to know why they didn’t take some of the people from Moruca as wardens. I held on because it was a sacrifice I had made to stay at Shell Beach with the objective to bring the turtle population up. That is what happened. It was a tough decision to leave Shell Beach and return home to Santa Rosa. When we first went up we would only see about four or five turtles in weeks and one or two persons with carcasses.”

While he was still at Shell Beach, James said, no one from the PAC sought advice from those who were there before.

“In my opinion they weren’t patrolling as they should have. When they go on patrols on the beaches, it is like excursions for them. They go in the mornings and come back in the afternoons.”

Because of this, he said, people are removing the eggs and slaughtering the turtles at nights.

The families who had made their home on the beach and had been actively involved in the protection of the turtles were no longer involved, James said, because of restrictions due to the PAC rules and regulations.

Relationship with fishermen and Venezuelans

“We had a good relationship with fishermen and other people. You have to talk to them nicely and share things with them.”

Noting that Venezuelans often came ashore at Shell Beach, James said, they never experienced any threats from them. “Instead we helped each other. Sometimes they came to ask for coconuts and we’d tell them to take as much as they could. The coconuts would start bearing in three years and one bunch would have about 30 or 40. Before they leave, they would fill our empty gas containers. It was like an exchange. Whenever we planted water melons and pumpkins and we get 100 or 200 or more we gave them because they were so much. Papaws we got by the thousands. We grew tomatoes, bora and carrots there, too. We were self-sufficient.

With his experience, James thinks he still has a lot to offer in terms of advice. The PAC wardens, he feels should continue to meet and to interact with turtle hunters. “I still want to go back out there to see what is happening. We can advise what they can do and what they shouldn’t do.”