One is not certain about the first flavors of “sweet drink” to be bottled in British Guiana. There is high probability that among the first was lemonade. According to recipes available from the late 19th century, lemonade may have been the dominant early flavor as the syrup could be concocted locally. According to Hamid Mohamed of the Verdun Soda Water Factory, “the lemonade formula was straight forward—lemon oil extract, white sugar, carbonated water, citric acid, and sodium benzoate.” This may explain the proliferation of lemonade bottlers in British Guiana from the early 20th century until their virtual extinction during the 1970s. Collectively, they are referred to as the “Lemonade People.”

One is not certain about the first flavors of “sweet drink” to be bottled in British Guiana. There is high probability that among the first was lemonade. According to recipes available from the late 19th century, lemonade may have been the dominant early flavor as the syrup could be concocted locally. According to Hamid Mohamed of the Verdun Soda Water Factory, “the lemonade formula was straight forward—lemon oil extract, white sugar, carbonated water, citric acid, and sodium benzoate.” This may explain the proliferation of lemonade bottlers in British Guiana from the early 20th century until their virtual extinction during the 1970s. Collectively, they are referred to as the “Lemonade People.”

The evidence suggests that the beverage was initially bottled in a variety of white bottles and later in the iconic 6 oz dark green or brown bottles. As a result, the beverage is known as the “small lemonade.” There was also a “large lemonade” in a 10 oz bottle. The “small lemonade” was personal and associated with public consumption, while the “large lemonade” was “family size” and associated with consumption at home. The “respectability and reputation” dynamic was at work here. In terms of urban decorum during the 1950s, “decent people” did not drink small lemonade in the public. Such was the behaviour of “stray boys” and “kangalangs.”

In the late 1950s, a “small lemonade” sold for approximately three cents (.50 cent per oz.) The bottlers of “small lemonade” were community-based. They were found in the urban, rural, and hinterland regions of the nation. A 1960 report from the Government Analyst’s Department stated that there were thirty-one (31) bottlers in operation in the colony.

During spring 2020, through a series of online conversations with my Facebook friends (n = 1,585) about the Guyanese sweet drink experience, I was able to generate, from those memories and reflections, a “map” of lemonade factories operating in Guyana during their lifetimes. Seventy-five percent of those friends were born in various parts of Guyana during, or since the end of World War II. Those conversations offered, with varying degrees of clarity, information, and opinion on the lived Guyanese sweet drink experience during the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, and the first two decades of the 21st century. When coupled with documentary and other sources, it was possible to identify and locate twenty-two (22) lemonade bottlers. In some cases, names of the factories were provided, in other cases the names of proprietors were given and, in a few cases, only the location of a former factory was provided. Lemonade bottlers were identified in Guyana’s three counties. In Demerara, nine (9) factories were identified in Georgetown:

- Excelsior Soda Factory (Adelaide Street)

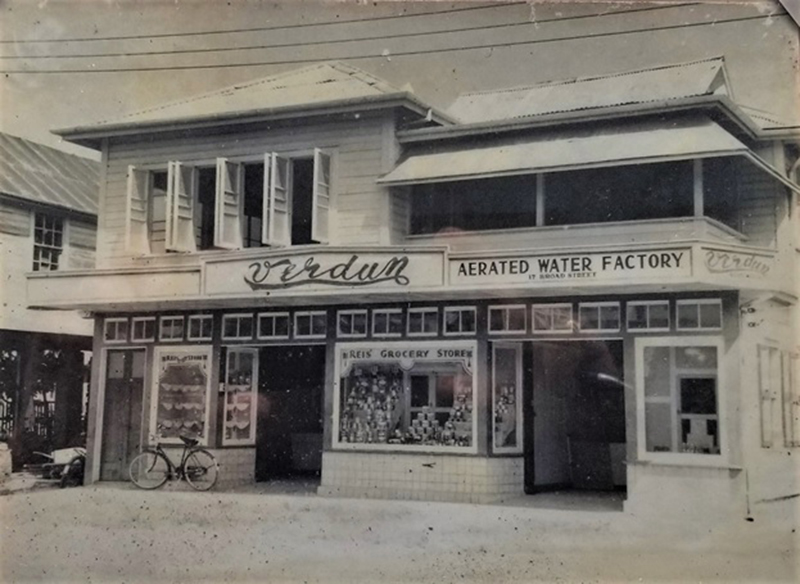

- Verdun Aerated Water Factory (Broad Street)

- Ramroop (Fru-T) (Broad Street)

- Jeboo (Broad Street)

- Virtue/DeRyck (North Road & Wellington Street)

- DeAbreu Factory or Guiana Aerated Water Factory (Regent & Albert Streets)

- Atlantic Soda Water Factory (Robb Street)

- Bottlers (Durban & Hardina Streets)

- Russian Bear (Schumacher Street)

- Two bottlers were identified on the East Coast of Demerara:

- Willems/Williams Lemonade Factory (Golden Grove)

- Belfield Aerated Water Factory (Belfield)

- Three bottlers were identified in West Demerara:

- London Pride (New Road, Vreed-en-Hoop)

- The Chee-A-Tows (Meten-Meer-Zorg)

- Khan’s Soft Drink Factory (Vergenoegen)

- Seven bottlers were identified in Berbice:

- R.A. Flavours (Rosignol)

- Popular Aerated Water Factory (New Amsterdam)

- Swamber Aerated Water Factory (New Amsterdam)

- Excelsior Soda Water Factory (New Amsterdam)

- J&D Factory [Jugal Persaud and Dow] (New Amsterdam)

- Joe’s Lemonade (Letter Kenny)

- Crown Spot Factory (Rose Hall)

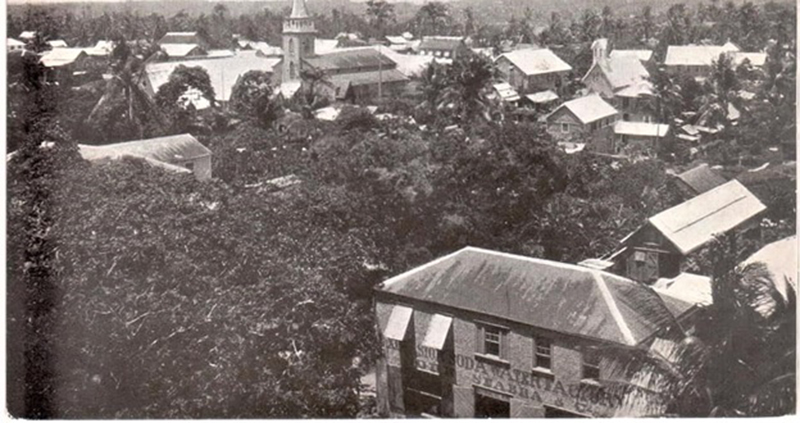

Two unnamed factories were identified in Essequibo. One in Alliance and the other in Bartica. These data, complemented with in-depth interviews and desk research permit the geographic, biographic, and operational details provided below. This listing is not presented as exhaustive. I remind you that the title of this series is A Preliminary exploration of the social history of sweet drinks in Guyana 1870 – 2020. There is still substantial work to be done on this aspect of the Guyanese experience.

The names Mumtaz Ali, Dow, Khan, DeAbreu, William De Ryck, Charles Jaijairam, Jeboo, Alfred Mohamed, Jugal Persaud, Ramroop, H. E. Reis, Roy and Norma Seabra, Antonio Soares, and Joseph “Yossi” Willems have special places in Guyana’s “sweet drink” history. These can be considered as some of the leaders among the Lemonade People. They all operated community-based establishments, closely associated with a ward, a town, or a village. All used the iconic small brown or green 6oz bottles. Some of the earlier operators such as William De Ryck, Alfred Mohamed, and Antonio Soares were known to use an earlier bottling technology—the marble stopper—thus the once popular term “marble lemonade.”

Like the D’Aguiar Bros, Carl Wieting, and Gustav Richter, the community-based bottlers were also trying their luck. Alfred Mohamed, the proprietor of the Verdun Soda Factory was the son of immigrants from India. DeAbreu, H.E. Reis, Antonio Soares, and Roy Seabra were probably immigrants or descendants of immigrants from Portugal. One of the participants in the Facebook conversations recalled that DeAbreu, the owner of the DeAbreu Aerated Water Factory (Guiana Aerated Water Factory) was still speaking Portuguese during the early 1950s. Joseph “Yossi” Willems was one of the few Jewish persons living in British Guiana during the 1940s and 1950s.

Another interesting aspect of the early community-based bottlers is the significant numbers who have Muslim backgrounds. Hemwant Persaud, a fellow student of the history of Guyanese beverages, suggests that this may be related to post-indenture dynamics in which formerly indentured Indian immigrants were seeking opportunities outside of the sugar economy. The Indian indentureship programme ended in 1916. Persaud noted that Indian immigrants with Hindu backgrounds invested in the alcohol business, operating spirit/rum shops. This business had previously been dominated by Portuguese and Chinese immigrants. Because of religious injunctions, Indian immigrants with Muslim backgrounds opted for investments in the non-alcoholic carbonated beverages economy. An additional explanation may be found in the experiences and tastes of our Indian ancestors prior to arrival in British Guiana. By 1834, there was an active aerated beverage industry in India. Calcutta and Madras, major embarking points for indentured labour to British Guiana, were major soft drink production centers. Among the popular flavors was a gerrah-flavored lemonade. It could be suggested that ventures into the “sweet drink” industry were not only a response to a business opportunity in a hot and humid place, but an effort to reestablish an ancestral taste culture. In the next installment we will profile a few of these entrepreneurs.

Vibert Cambridge is Professor Emeritus, School of Media Arts and Studies, at Ohio University

SELECTED REFERENCES

Department of the Government Analyst. Annual Report 1960.

Sulz, C. Part Eight, “Carbonated and Saccharine Beverages” in A Treatise on Beverages or the Complete Practical Bottler. New York: Dick & Fitzgerald Publishers, 1888, pp. 587 – 818.

Patel, D. “How Parsis shaped India’s taste for soft drink.” BBC News, March 22, 2020.