When the waters off Tobago develop visible lines and turn dark and cloudy, experienced sea folks know from one look that the weather has been bad, more than a 100-miles away, in South America.

Divers are particularly cautious going through the vertical divisions called haloclines that may alternate between milky green, pale blue and heavy brown. Given the poor visibility at some levels, they stay close in the fast-moving currents and far away from treacherous shoals, reminded by their watchful guides of the standard one-minute search pattern in case of separation.

Bearing mud and sediment discharged from the rain-swollen Orinoco and Amazon Rivers, noticeable plumes spread across in the dominant Guiana Current, reaching the shores of the island and its bigger sister Trinidad, and far out into the Atlantic Ocean.

Fed by the North Brazil version, a major source of nutrient-rich water for the Caribbean Sea, the Guiana Current eventually mixes with other tropical currents, feeding the critical circulation of the North Atlantic subtropical Gyre, which helps drive the oceanic conveyor belt that regulates the temperature, salinity and food flow.

This complex network of currents is among the obstacles, the twin-islands’ authorities faced back in April 2000, searching hundreds of miles, for any signs of the nine-man crew or wreckage from the still missing general cargo vessel, the “Gran Rio R,” owned by the Guyanese businessman, Dennis Rambarran, who died a few years ago.

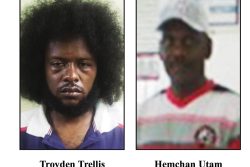

Presumed lost off the choppy south-western coast of Tobago, the 225-foot steel and diesel-motor boat sported a flag of convenience from St Vincent and the Grenadines that would mean the men’s families were never adequately covered or compensated for the loss of their loved ones, nearly all of whom were the sole breadwinners. Aboard were the Captain Michael Paul, also known as Patrick Paul, 54; Chief Mate, Morris Mangru, 37; Chief Engineer, Indarpaul Latchman, 40; Second Engineer, John Karpan, Jnr, 35, a US citizen; Third Engineer, Phillip Scott, 21; the vessel’s cook, Ravanand Persaud, 33; and Michael Joseph, 28, Muhammed Inshan, 41, and Rummel Wilson 25, sailors.

Looking through documents provided by Mr Karpan’s relatives, I found a letter from his late father John Karpan Snr, desperately seeking information about whether his son’s wife and newborn baby would be covered by American social security or Guyanese insurance. In it, Mr Karpan Snr, complained, “He will not return our calls” in reference to Mr Rambarran, who operated Rambarran Trading and Shipping.

But Mr Rambarran did talk to a high-ranking official from the United States (US) Embassy in Guyana, who contacted him after. According to the June 4, 2000 fax forwarded to the family, the official wrote, “He stated that he does not have any insurance on his ship and said he wasn’t required to have any. He added that it was too expensive and that he had discontinued having insurance many years ago. Please bring this to the attention of anyone who is providing you with legal advice.”

On Wednesday, a relative of Chief Mate, Mr Mangru said that impoverished and bereaved Guyanese families had not considered taking legal action against the negligent owner because of the prohibitive costs and the lax laws protecting seamen here. Dozens of Guyanese crew have disappeared over the last two decades in a demanding profession that has proved deadly.

Twenty-one years later, from the vanishing of the “Gran Rio R,” Guyana still has not ratified the Maritime Labour Convention (MLC), 2006, and at least 44 other key instruments, according to online data from the International Labour Organization (ILO). However, St Vincent and the Grenadines stepped up in November 2010, depositing its ratification of the MLC.

While writing this column I realised that since the “Gran Rio R” had a gross tonnage of 990 and a deadweight of 1219, there is no way the much cited 1500 tonnes of silica sand it was reportedly carrying, could be correct.

In many media reports, Mr Rambarran had repeatedly pointed to the presence of an Emergency Position-Indicating Radio Beacon (EPIRB) which should have been triggered aboard the ship. But the locator is a portable, battery-powered radio transmitter and can only work if is activated by a crew member in time, the battery is viable or if the frequency is the one monitored by search-and-rescue-teams.

The continuous radio signal is detected by satellites operated by an international consortium of rescue services from 43 countries and agencies, called COSPAS-SARSAT, which can find emergency beacons anywhere on Earth, if transmitting on the COSPAS distress frequency of 406 MHz. The cooperative calculates the position of the beacon and passes the information to the appropriate local first responder group, in this case the T&T Coastguard.

However, older beacons that send out only a legacy analogue signal on 121.5 MHz or 243 MHz rely on being received by nearby aircraft or rescue personnel if these are close enough. Some can be manually activated by a person pressing a button, others are designed for automatic activation like a crash or water, but given what we know about the “Gran Rio R” the latter, more expensive version was unlikely to have been aboard in 2000.

The modern EPIRB, often termed GPIRB, contains a GPS receiver and broadcasts its position, usually accurate within 100 metres (330 feet). Previous emergency beacons without a GPS can only be localised to within 2 km (1.2 miles) by the COSPAS satellites.

The basic purpose is to try and find survivors within the so-called “Golden Day” or the first 24 hours following a traumatic event, experts explained. In the “Gran Rio R’s” case, uncertainty remains about who and when the crew supposedly contacted that it was taking on water and would require a standby pump when it docked at Crown Point, ranging from the crew of a sister company vessel around 5:25 p.m. to a late night weak alert allegedly picked up by TT’s Coastguard in Staubles Bay, Chaguaramas.

It was not until about 11 a.m. the next day that the alarm bells started ringing. The first air search did not begin until 1 p.m. and by then the currents had long surged past the dreaded Drew Bank, a lounger-shaped area marked by two dangerous shoals, the Wasp at the northern extremity and the Drew at the other.

For centuries, sailors have learnt to avoid Drew Bank, lying on a 40-metre curve just outside of Crown Point. Marine manuals warn that it is usually marked by “overfalls” or turbulence caused by tidal currents moving over the seabed. Unexpected and heavy breakers form even in the calmest of weather, and the fairway of the channel between Wasp Shoal and Crown Point has depths of 16 to 33 metres (53-108 feet).

As University of the West Indies (UWI) Professor Julian Kenny, a former Senator, warned in his book “Views from the Ridge: Exploring the Natural History of Trinidad and Tobago,” the oceanic currents entering the Bank’s shallow waters causes unexpected leaps in velocity to several knots.

It is here that the secrets of the “Gran Rio R” are believed to be buried by sand – and now, coral.

ID thinks of the relatives of the “Gran Rio R” sailors including the niece who grieves and writes, “I know one day we will all see you again and the rest of the crew, we always pray for that day to come… I love you Uncle Morris.”