There has always been competition in the Guyanese aerated drink market. The persistent impulse among domestic and international bottlers and distributors has been to stimulate the consumption of the sugary beverages to increase market share. We call this the “sweet drink wars”: the battles for the palate in hot and humid Guyana.

There has always been competition in the Guyanese aerated drink market. The persistent impulse among domestic and international bottlers and distributors has been to stimulate the consumption of the sugary beverages to increase market share. We call this the “sweet drink wars”: the battles for the palate in hot and humid Guyana.

As we saw in a previous installment, the Berbice bottlers resorted to destroying the competition’s bottles in their fight for market share. The sweet drink wars in British Guiana intensified between the 1940s and the 1970s: from the end of World War II to the mid-1970s when a severe foreign exchange crisis crippled the Guyanese economy. The battle involved three urban companies: D’Aguiar Brothers Ltd., Wieting and Richter’s (W&R’s) Cold Storage and Ice Depot, and the Rahaman Soda Factory. They developed new technologies, established national distribution systems, and launched innovative marketing and promotion campaigns that invoked hygiene- and ideology-related narratives. The sweet drink wars in Guyana have always featured geopolitical, class, ethnic, and community dimensions.

I pick up the story during World War II. On September 2, 1940, the United States and Great Britain signed the Destroyer-for-Bases Agreement. A 99-year lease facilitated the United States’ establishment of an airbase at Hyde Park on the east bank of the Demerara River (now Timehri) and a seaplane or naval base on the west bank of the Essequibo River. American military personnel remained in the colony until 1966, when British Guiana gained its independence.

At the start of World War II, both Coca-Cola and Pepsi Cola were expanding their domestic and international operations. Both companies supported the American war effort. Robert W. Woodruff, President of the Coca-Cola Company, declared that it was his company’s intention to “see that every man in uniform gets a bottle of Coca-Cola for five cents, wherever he is and no matter what the cost.” He was gambling on the proposition that when the troops returned from overseas campaigns, they would remain Coca-Cola consumers. In 1941, Pepsi Cola adopted the red, white, and blue logo to express its support for the American war effort.

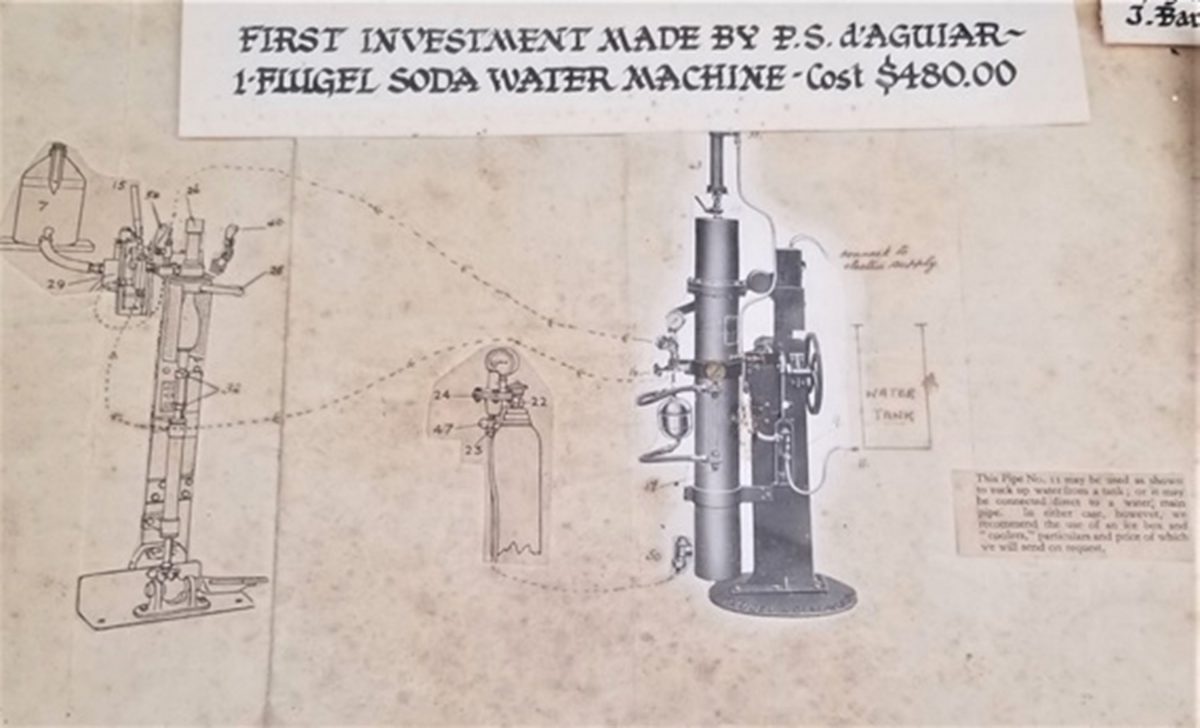

Coca-Cola and Pepsi Cola were available in British Guiana during World War II. Wieting and Richter had the Coca-Cola franchise. The Banks DIH website indicates that the company acquired the first Pepsi-Cola franchise in South America in 1942. This was indicative of the significant changes in the company. In 1939, Peter Stanislaus D’Aguiar, the U.K.-educated grandson of José Gomes d’Aguiar, became the managing director. According to the company’s narrative, Peter D’Aguiar “relinquished” the cocoa, chocolate, and schooner shipping businesses to concentrate on bottling. The company’s museum, located in the rotunda at Thirst Park, has an illustration of the first bottling equipment Peter D’Aguiar bought. It was in bottling technologies from Flugel Co. Ltd.

By about 1952, DIH had launched the I-Cee brand of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages. Among the initial I-Cee flavors were cream soda, orange, and tonic. I-Cee lemon was launched in 1961. The I-Cees were the large (10 oz) drinks. DIH also bottled small (6 oz) drinks, such as Lime Rickey, ginger ale, and soda water, under the Club brand. These were “mixers,” which were targeted to hotels, clubs, and bars. Another small drink bottled by DIH during the 1950s and early 1960s was Vimto. Vimto, whose trademark was registered in British Guiana in 1919, has enjoyed prestige in the society’s sweet drink culture.

Coterminous with this expansion was a series of assertive marketing and public relations efforts aimed at increasing D’Aguiar Bros’ market share and dominating the market. Wieting and Richter’s Cold Storage and Ice Depot (CSID), with the Coca-Cola, Juicee, and Star brands, sought to defend its market share, maintain brand loyalty, and increase consumption of its fizzy products. One of CSID’s strategies was providing free “Cokes” for school children attending the annual Empire Day rallies in Georgetown.

During the early post-World War II years, the fight for British Guiana’s sweet drink market was primarily between D’Aguiar Bros., Ltd and Wieting & Richter. However, by 1950, there was another player, the Rahaman Soda Factory, located in Houston on the East Bank Demerara. The company started with the Wonder brand of lemonade after the end of World War II. By the early 1950s, it was bottling the Red Spot brand under a franchise relationship with S. M. Jaleel of Trinidad and Tobago. At its launch, the Red Spot brand had more flavors than any bottler in colony. There was banana, ginger beer, grape, grapefruit, Kola Champagne, Lime Rickey, pineapple, and R S Cola, along with the traditional orange, cream soda, and ginger ale. Among its marketing slogans was “Always Refreshing.” The company, located in Rahaman’s Park, Houston, East Bank Demerara, was solely owned by Hajji Meer Amjad Ally Rahaman, the son of Meer Abdul Rahaman, the founder of the Peter’s Hall mosque.

In 1958, the Rahaman Soda Factory acquired the Coca-Cola franchises for Demerara, and on Monday, June 9, 1958, it launched the 12 oz king-sized Coke from a new and technologically advanced factory. A regular 6.5 oz bottle of Coca-Cola cost 7₵ (US 3.5₵), and a king-size bottle was 8₵ (US 4₵). The opening of the Coca-Cola factory was covered extensively in the press. The Daily Argosy of Saturday, June 7, 1958, carried an extended story that included a photograph from the press conference held at the Palm Court in Georgetown the previous day. In the photograph were Cyril White, managing director of The Argosy Company; Ulric Gouveia, with Radio Demerara; M. A. Rahaman; and Juan Basseda, regional manager of The Coca-Cola Company. The report stated that Basseda had “flown in from Havana, Cuba to be present at the press conference.”

The opening of the Coca-Cola factory occurred at an important moment in British Guiana’s Cold War experience. Beginning in 1953, the United States and its allies had concerns about British Guiana becoming a base for Soviet expansionism in the Americas. For the United States, this was unacceptable. In 1953, the colony’s first government elected under universal adult suffrage was declared to have been pro-Communist. It was ousted from office after 90 days. According to Dr. Cheddi Jagan:

“Soon after the suspension of the constitution in 1953, the British government moved quickly and launched what Emrys Hughes, British M.P., called ‘rule by the iron hand and wooden head.’ The kid glove gave way to the mailed fist.”

Between 1953 and 1957, British Guiana was administered by an interim government, whose explicit goal was to promote capitalism as the engine of social and economic development. When the Rahaman Soda Factory launched its Coca-Cola line in June 1958, the People’s Progressive Party, under the leadership of Dr. Cheddi Jagan, had returned to power. His electoral base, the Indo-Guianese population, remained loyal during the August 12, 1957, general elections. In June 1958, Coca-Cola’s regional manager’s office was in Havana, Cuba, while Fulgencio Batista was in power.

The opening of a new Coca-Cola bottling plant in British Guiana represented a development model promoted by U.S. foreign policy. It has been referred to as franchise capitalism. Simply stated, in this model, the developing world would leap into the world of industrialization through franchise relationships with American private sector corporations. Not only would this accelerate “modernization,” but it would also quickly provide employment, increase consumption, and, in the process, stop the spread of communism. In British Guiana in 1958, Coca-Cola represented private investment, a sacrosanct value system to be promoted and defended, as was democracy within the American sphere of influence.

Prior to the Rahaman company’s becoming the “newly authorized Coca-Cola bottler for Demerara,” the brand’s bottler in British Guiana was W&R’s CSID. However, by the late 1950s, its bottling plant had grown old and, consequently, was unable to meet Coca-Cola’s quality specifications. According to members of the Rahaman family, “Coke approached [their] grandfather to take over their franchise from W&R. W&R had failed to meet Coke’s standards.”

Senior Coca-Cola executives made many visits to the Rahaman Soda Factory during the early years of the franchise. One such, was the 1961. The Evening Post of May 12, 1961, reported a routine visit by Mr. Montague Thomas, vice president of the Coca-Cola Inter-American Corporation and the Coca-Cola Export Corporation. Thomas is reported to have reiterated that the Rahaman Soda Factory plant was “one of the finest in the region, which includes the Caribbean islands, and the three Guianas.”

Also accompanying the Coca-Cola vice president was Mrs. M. Thomas. Another article in the May 12 Evening Post indicated that “late last year [1960] the Cuban government confiscated the Coca-Cola Company and the belongings of Mr. and Mrs. M. Thomas both Americans.” Coca Cola’s regional head office was now in Nassau, Bahamas. These were intense ideological times in the hemisphere!

In late 1972, W&R relocated its bottling plant from Water Street to the Ruimveldt Industrial Estate. It eventually reacquired the Coca-Cola franchise, which it maintained until December 1975, when its operations were acquired by Banks DIH, which was also located in the Ruimveldt Industrial Estate. In 1970, Hajji Meer Amjad Ally Rahaman died, and the company was acquired by his sons Meer Hamaz, Meer Imran, and Meer Ansari. The company name was changed to the Republic Soda Factory. By the early 1970s, all three of Guyana’s dominant bottlers were located relatively close to one another on East Bank Demerara.

The companies’ advertising and marketing campaigns have played pivotal roles in creating awareness and stimulating the consumption of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages in post-World War II British Guiana. The outcomes of those campaigns still resonate in Guyana. In the sweet drink war, there were many casualties, especially among the Lemonade People and other small community-based bottlers. Many had been in business since the early 20th century. These bottles of fizz, especially the franchised brands, were ascribed a higher social status. They not only challenged the small lemonade, but they also marginalized homemade drinks as thirst quenchers and refreshers. The franchised sweet drinks were positioned as healthy symbols of modernity and sophistication. The Lemonade People and the community-based bottlers were framed as unsanitary. The next installment will examine some of the tactics deployed in the sweet drink wars.

SELECTED REFERENCES

Coke vs Pepsi: The Amazing story behind the Cola Wars.” Available online at: https://www.businessinsider.com/soda-wars-coca-cola-pepsi-history-infographic-2011-11#pepsi-cola-was-created-in-13-years-later-by-pharmacist-caleb-bradham-2

Carew, I. “Atkinson Field and World War II: A Memoir 1943 -1946.” Stabroek News, July 7, 2011. Available online at https://www.stabroeknews.com/2011/07/07/guyana-review/atkinson-field-and-world-war-ii/?fbclid=IwAR3qnFZUwIoccpdFA9gVU9-2CPmapXX1_fdEX8itAx8PsCyFp7pxpHw_SC8 Retrieved June 8, 2020 T 4:35 P.M.

“The Sun Never Set on Cacoola,” in TIME Magazine 5/15/1950. Volume 55 Issue 20, pp 28 – 32.

United States, Bureau of International Commerce. Business Firms, Guyana. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Department of Commerce, 1968, p. 16. Available at: https://books.google.com/books?id=LrjvaDjVFLUC&ppis=_e&dq=Rahaman+Soda+Factory&source=gbs_navlinks_s

Cambridge, V. Facebook conversation, “The Geography of ‘Sweet Drinks’ in Guyana” launched April 21, 2020. https://www.facebook.com/vibert.cambridge/posts/10157045271290849?comment_id=10158058760755849¬if_id=1624887773436591¬if_t=feed_comment&ref=notif