(for Big Yout)

1

muzik of blood

black reared

pain rooted

heart geared

all tensed up

in di bubbe an di bounce

an di leap an di weight drop

it is di beat of di heart

this pulsing of blood

that is a bubblin bass

a bad bad beat

pushin against di wall

whey bar black blood

an is a whole heappa

passion a gather

like a frightful form

like a righteous harm

giving off wild like is madness

[. . .]

5

culture pulsin

high temperature blood

swingin anger

shattering di tightened hold

the false hold

round flesh whey wail freedom

bitta cause a blues

cause a maggot suffering

cause a blood klaat pressure

yet still breedin love

far more mellow

than di soun of shapes

chanting loudly

[. . .]

7

for di time is nigh

when passion gather high

when di beat jus lash

when di wall mus smash

an di beat will shiff

as di culture alltah

when oppression scatta

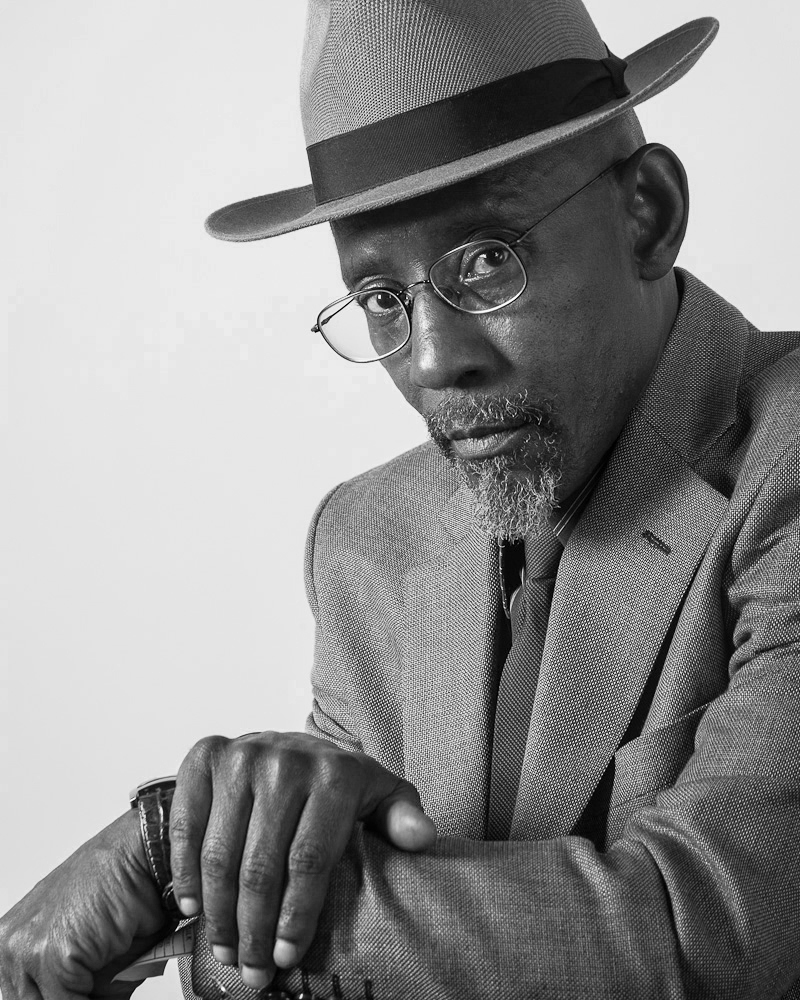

– Linton Kwesi Johnson

Early this month, the cities of London, England and Kingston, Jamaica mourned the loss of Jean “Binta” Breeze (died August 4, 2021). Last week, the worldwide literary community hailed the birthday, on August 24, of poet Linton Kwesi Johnson. Both were rites of passage, celebrating different chapters in that deep brand of West Indian literature known as dub poetry. It is a form that has been both brooding and celebratory, but marks the influential blend of the oral and the scribal in the literature.

Breeze exemplified the exalted and influential place attained by dub poetry in both West Indian and English poetry, as does Johnson. Breeze lived in the UK for most of her long career and was honoured by the Queen with an MBE for her services to literature.

Johnson lives in London from where he has practiced as a performance poet since the 1970s. He is recognised as a pioneer of the form and the most outstanding dub poet. He is an Associate Fellow of the University of Warwick and is among the most highly decorated Jamaican poets. Apart from several university fellowships and honorary titles, including a doctorate from Rhodes University in South Africa (2017), he was awarded a Golden PEN by the English PEN in 2012 for a Lifetime’s Distinguished service to literature, and a silver Musgrave Medal by the Institute of Jamaica for distinguished eminence in the field of poetry.

Additionally, Johnson’s native land bestowed on him the Jamaican national honour of the Order of Distinction in 2014. Most recently, in the UK, he won the prestigious PEN Pinter Prize, named for Nobel Laureate Harold Pinter, the British playwright. In a most impressive citation, the judges described Johnson as, “a living legend, a poet, reggae icon, academic and campaigner whose impact on the cultural landscape over the past half a century has been colossal and multigenerational . . . his political ferocity and his tireless scrutiny of history are truly Pinteresque, as is the humour with which he pursues them”.

Such is the impact and influence of his work and the heights to which he has taken dub poetry. These achievements were all hailed on his birthday. He was born in the town of Chapelton in Jamaica and migrated with his parents to England in 1963. He lived in Brixton, that troubled South London community, and earned a degree in Sociology from University of London. He started writing in London at the beginning of the 1970s, but was closely in touch with developments in Jamaica when dub poetry emerged around that time.

One of the main contributing elements was the music, reggae, which evolved late in the 1960s out of ska, that had transitioned into rock steady. Created in the Kingston ghettos, this form which both shaped and was shaped by the popular culture, was already reflecting the prevailing social phenomena such as the rude by era, with its dancehalls, escalating violence, defiance and rebellion.

Added to this were the contingent political developments involving the right wing, capitalist Jamaica Labour Party government, which came into conflict with popular resistance. These included communist sympathies, black power, growing social commitment and relevance out of the university academic community, middle-class acceptance of black and African consciousness, Rastafari and reggae music. This music was increasingly becoming a medium of social and political protest.

When the government, troubled by these developments, expelled Walter Rodney from the country, it triggered a succession of responses and situations. The student protests and other campus and academic responses, took effect in Jamaica and elsewhere in the Caribbean. In spite of government action to isolate the campus community, the Mona Campus and the wider population grew closer together, mainly through the series of cultural developments that followed.

Already there were important literary currents. Mervyn Morris had published “On Reading Louise Bennett Seriously”, an essay which had won the 1963 Jamaica Festival Essay competition, and in 1966 Rex Nettleford edited Jamaica Labrish, a collection of Louise Bennett’s poems, with notes. These were the most serious victories in favour of not only Bennett’s acceptance into mainstream West Indian literature, but an extremely influential advance of creole poetry. A revolutionising of the language of West Indian literature was set in train, particularly in concert with the publication of Kamau Brathwaite’s trilogy – Rites of Passage, Masks and Islands.

In the aftermath of the Rodney episode, public poetry readings escalated in grassroots settings and contexts, which strengthened the oral qualities in the literature and extended the growth of poetry in the language of the people. Mainstream poets, such as Morris, Brathwaite and Dennis Scott, read their work in these performances, which were prominent around 1970. The alliance of music, in particular drumming, with poetry readings was a significant factor which brought poetry and music even closer together.

Further, by 1970, reggae was already a medium of dissent with its narratives, analysis and protest against social and political conditions. One strand of reggae was particularly innovative – the DJ dub — with notable performers like Big Youth and Hugh Roy extending the boundaries of the music with significant oral expressions.

In 1971, when Savacou ¾, edited by Brathwaite, Andrew Salkey and Ken Ramchand on the Mona Campus, published a collection of new poetry and short prose, it was so radical, so new and unconventional that it was earth-shaking where West Indian literature was concerned. The editors wanted to reflect what was being written at the time, including new styles and forms. Robert Stewart in “Linton Kwesi Johnson: Poetry Down A Reggae Wire” explains the thinking of the editors behind the publication which met with some strong criticism about quality and content. The strongest resistance came from Trinidadian poet Eric Roach who, in the Trinidad Guardian July 14, 1971, condemned the tendency to continue wallowing in the murky waters of race and slavery. The most comprehensive defence of Savacou 3/4 came from Gordon Rohlehr who, responding to Roach, thoroughly analysed the work , recognising how it reflected new thinking and new forms in a changing and developing West Indian literature.

Closely allied to this was the emergence of dub poetry, a new form in keeping with those developments reflected in Savacou. It took its name from reggae recordings which consist only of the basic instrumental from a musical track – really just the minimum of drum and guitar. A poem would be read against the sound of this track or dub.

But this new form was more than simply a poem accompanied by reggae. Dub poetry is performed in Creole (or Jamaican Patois) and is the voice of the voiceless in society. The persona is the poet himself or a dramatised character from the working class or ghetto. It is protest-verse or expressive of the unprivileged at the bottom of the social ladder. The politics of dub poetry is radical and emerged from the black struggle and the new voices of 1970 among issues of oppression, race and resistance.

Among the earliest performers were Mutabaruka (formerly Alan Hope or Alan Mutabaruka), Bongo Jerry, Oku Onoura (formerly Orlando Wong) and Mikey Smith. Morris was again instrumental in hastening the recognition of this form in the mainstream, by his editorship and attention to Smith, achieving as much for dub poetry as he did for Bennett.

Johnson, from his base in London, was much in tune with the developments in Jamaica and was the first to emerge as a published dub poet. His early work, “Sonny’s Lettah”, is an excellent example of this. So is “Five Nights of Bleeding”, which came out of his verses of resistance against conditions in the UK. The poems decry police brutality, conditions against black youth in the UK, the Brixton riots of 1981, but he also took in European politics as well as tragic Caribbean themes as in “Reggae Fi Radni” and “Reggae Fi Dada”.

Johnson’s versatility is also worth mentioning. There is that memorable recording he did of Martin Carter’s “Poems of Shape and Motion” recited to a background of reggae rhythms. So inspiring was it, Guyana’s National Dance Company used it in one of its outstanding dances choreographed by Vivienne Daniel.