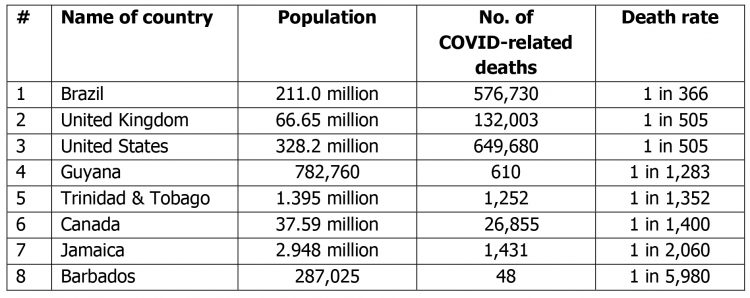

Guyana’s Health Minister has stated that the Delta variant of the COVID-19 pandemic may be in Guyana, judging from the spike in the number of COVID-19 cases in the last week or so. The variant has been found in more than 140 countries. In fact, Trinidad has confirmed that a traveller from Guyana was tested positive for the variant. According to the Minister, as the Delta variant becomes dominant, we are likely to see more cases of infections, hospitalization and deaths. Here are the latest statistics of COVID-related deaths from selected countries, including Guyana (in order from the most serious):

On the climate change front, it has been conclusively established that burning fossil fuels is the main source of the greenhouse gas emissions that are heating the planet. However, there has been no collective effort so far by governments to end oil and gas production. In this regard, Denmark and Costa Rica are trying to forge an alliance of countries willing to fix a date to phase out oil and gas production and to stop giving permits for new exploration. The International Energy Agency has stated that there should be no new investments in fossil fuel supply projects anywhere in the world if the targets set by the Paris Agreement are to be met. The United Nations Secretary-General has issued a similar call to countries to end all new fossil fuel exploration and production, and shift fossil fuel subsidies into renewable energy.

Last year, Denmark, one of the largest oil and gas producers in Europe, banned new oil and gas exploration and committed to ending its existing production by 2050. Although Costa Rica has never extracted oil, it is considering a bill to permanently ban fossil fuel exploration to ensure no future governments do so. New Zealand has also banned new permits for offshore oil in 2018, while the United States, the world’s largest producer of oil and gas, pledged to cut its emissions by half by 2030, from 2005 levels. France and Spain have also committed to end the use of fossil fuels by 2040 and 2042, respectively.

On 7 August 2021, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) issued its report titled “Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis”. The report provides a high-level summary of the understanding of the current state of the climate, including how it is changing and the role of human influence, the state of knowledge about possible climate futures, climate information relevant to regions and sectors, and limiting human-induced climate change.

In today’s article, we begin our coverage of the main points in the report.

Increase in greenhouse gas concentrations

The report made it clear that ‘[i]t is unequivocal that human influence has warmed the atmosphere, ocean and land. Widespread and rapid changes in the atmosphere, ocean, cryosphere and biosphere have occurred’. It all started around 1750 when the Industrial Revolution began. However, since 2011, the date of the last IPCC report, greenhouse gas concentrations have continued to increase in the atmosphere, reaching annual averages of 410 ppm for carbon dioxide (CO2), 1,866 ppb for methane (CH4), and 332 ppb for nitrous oxide (N2O) in 2019.

Each of the last four decades has been successively warmer than any decade that preceded it since 1850. In particular, global surface temperature in 2001-2020 was 0.99°C higher than in 1850-1900, while in 2011– 2020, it was 1.09°C higher, with larger increases over land than over ocean. The estimated increase in global surface temperature since the last report is principally due to further warming since 2003–2012.

Global average precipitation over land has increased since 1950, with a faster rate of increase since the 1980s. It is likely that human influence contributed to the pattern of observed precipitation changes since the mid-20th century. It is also extremely likely that human influence contributed to the pattern of observed changes in near-surface ocean salinity. Mid-latitude storm tracks have likely shifted poleward in both hemispheres since the 1980s, with marked seasonality in trend. For the Southern Hemisphere, human influence very likely contributed to the poleward shift of the closely related extratropical jet.

Human influence is very likely the main driver of: (i) the global retreat of glaciers since the 1990s and the decrease in Arctic sea ice area between 1979–1988 and 2010–2019; (ii) the decrease in Northern Hemisphere spring snow cover since 1950; and (iii) the observed surface melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet over the past two decades.

Unprecedented changes across the climate change system

The scale of recent changes across the climate system as a whole and the present state of many aspects of the climate system are unprecedented over many centuries to many thousands of years. In 2019, atmospheric CO2 concentrations were higher than at any time in at least 2 million years, while concentrations of CH4 and N2O were higher than at any time in at least 800,000 years.

Since 1750, increases in CO2, CH4 and N2O concentrations far exceed the natural multi-millennial changes between glacial and interglacial periods over at least the past 800,000 years. Global surface temperature has increased faster since 1970 than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2,000 years. Temperatures during the most recent decade (2011–2020) exceed those of the most recent multi-century warm period, around 6,500 years ago. Prior to that, the next most recent warm period was about 125,000 years ago.

In 2011–2020, annual average Arctic sea ice area reached its lowest level since at least 1850. Late summer Arctic sea ice area was smaller than at any time in at least the past 1,000 years. The global nature of glacier retreat, with almost all of the world’s glaciers retreating at the same time since the 1950s, is unprecedented in at least the last 2,000 years. Global mean sea level has risen faster since 1900 than over any preceding century in at least the last 3,000 years. The global ocean has warmed faster over the past century than since the end of the last deglacial transition around 11,000 years ago.

A long-term increase in surface open ocean pH occurred over the past 50 million years, and surface open ocean pH as low as recent decades is unusual in the last two million years. (pH is a measure of how acidic/basic water is. The range goes from 0 to 14, with 7 being neutral. pHs of less than 7 indicate acidity, whereas a pH of greater than 7 indicates a base. The pH of water is a very important measurement concerning water quality.)

Effects on the weather

Human-induced climate change is already affecting many weather and climate extremes in every region across the globe. Evidence of observed changes in extremes such as heatwaves, heavy precipitation, droughts and tropical cyclones attributable in particular to human influence, has strengthened since the last IPCC report. Hot extremes (including heatwaves) have become more frequent and more intense across most land regions since the 1950s, while cold extremes (including cold waves) have become less frequent and less severe, with high confidence that human-induced climate change is the main driver of these changes. Some recent hot extremes observed over the past decade would have been extremely unlikely to occur without human influence on the climate system. Marine heatwaves have approximately doubled in frequency since the 1980s, and human influence has very likely contributed to most of them since at least 2006.

The frequency and intensity of heavy precipitation events have increased since the 1950s over most land area, and human-induced climate change is likely the main driver. Human-induced climate change has contributed to increases in agricultural and ecological droughts in some regions due to increased land evaporation. Human influence has also likely increased the chance of compound extreme events since the 1950s. This includes increases in the frequency of concurrent heatwaves and droughts on the global scale; fire weather in some regions of all inhabited continents; and compound flooding in some locations.

Decreases in global land monsoon precipitation from the 1950s to the 1980s are partly attributed to human-caused Northern Hemisphere aerosol emissions, but increases since then have resulted from rising greenhouse gases concentrations. Over South Asia, East Asia and West Africa increases in monsoon precipitation due to warming from greenhouse gas emissions were counteracted by decreases in monsoon precipitation due to cooling from human-caused aerosol emissions over the 20th century. Increases in West African monsoon precipitation since the 1980s are partly due to the growing influence of greenhouse gases and reductions in the cooling effect of human-caused aerosol emissions over Europe and North America.

The global proportion of major (Category 3–5) tropical cyclone occurrence has increased over the last four decades, and the latitude where tropical cyclones in the western North Pacific reach their peak intensity has shifted northward. Various studies indicate that human-induced climate change increases heavy precipitation associated with tropical cyclones.

Increase in radiative forcing

The IPCC defines radiative forcing as a measure of the influence a given climatic factor has on the amount of downward-directed radiant energy impinging upon earth’s surface. Human-caused radiative forcing of 2.72 W m–2 in 2019 relative to 1750 has warmed the climate system. This warming is mainly due to increased greenhouse gas concentrations, partly reduced by cooling due to increased aerosol concentrations. The radiative forcing has increased by 0.43 W m–2, or 19 percent, since the last report, of which 0.34 W m–2 is due to the increase in greenhouse gas concentrations since 2011.

Human-caused net positive radiative forcing causes an accumulation of additional energy (heating) in the climate system, partly reduced by increased energy loss to space in response to surface warming. The observed average rate of heating of the climate system increased from 0.50 W m–2 for the period 1971–2006 to 0.79 W m–2 for the period 2006–2018. Ocean warming accounted for 91 percent of the heating in the climate system, with land warming, ice loss and atmospheric warming accounting for about 5 percent, 3 percent and 1 percent, respectively.

Heating of the climate system has caused global mean sea level rise through ice loss on land and thermal expansion from ocean warming. Thermal expansion explained 50 percent of sea level rise during 1971– 2018, while ice loss from glaciers contributed 22 percent, ice sheets 20 percent and changes in land water storage 8 percent. The rate of ice sheet loss increased by a factor of four between 1992–1999 and 2010–2019. Together, ice sheet and glacier mass loss were the dominant contributors to global mean sea level rise during 2006-2018.

To be continued