As the coronavirus pandemic continues to ravage the global community with no hard immediate-term evidence of a respite in sight, a mid-August World Bank report says that an increasing number of countries across the globe are facing growing levels of acute food insecurity which carries with it the threat of a likely reversal of several years of development gains.

The Bank’s report says that even prior to the onset of COVID-19, reduced incomes and disrupted supply chains as well as chronic and acute hunger were already on the rise on account of factors that include conflict, socio-economic conditions, natural hazards, climate change, and pests. The advent of COVID-19, the World Bank says, has proceeded to add significant insult to the extant injury through “severe and widespread increases in global food insecurity, affecting vulnerable households in almost every country.” Worse, the report adds that these impacts are likely to continue through 2021, into 2022, and possibly beyond as the world witnesses the spread of the Delta variant of the pandemic.

The World Bank’s statistical overview of the global food insecurity crisis further accentuated by the pandemic indicates that the Agricultural Commodity Price Index remained near its highest level since 2013, and that as of July 16, 2021, was approximately 30% higher than in January 2020. Maize, wheat, and rice prices, were about 43%, 12% and 10% respectively, above their January 2020 levels.

Asserting that the international community now finds itself confronted with what would appear to be a worsening crisis, the World Bank says that the primary risks to food security exists at the country level adding that higher retail prices coupled with COVID-19-induced reduced incomes have meant that more households are compelled to reduce both the quantity as well as the quality of their food consumption.

Going forward, the Bank says that several countries are, even now, anticipating further high food-price inflation at the retail level, reflecting lingering COVID-19-related supply disruptions, social distancing measures, currency devaluations, and other factors.

Unsurprisingly, the Bank asserts that continually rising food prices continue to have a greater impact on people in low- and middle-income countries, particularly those with weak agricultural systems since these tend to spend a larger share of their incomes on food than people in high-income countries. Surveys undertaken by the Bank in forty-eight countries including several in Africa and Asia show a significant number of people running out of food or reducing their consumption. Contextually, the Bank asserts that reduced calorie intake and compromised nutrition threaten gains in poverty reduction and health and could have lasting impacts on the cognitive development of young children.

If the Caribbean is not, as a whole, facing an imminent threat of a COVID-19-related food crisis, recent assessments of food security in the region point to likely future challenges to its food security status resulting from worsening adverse weather conditions, less than significant gains in the expansion of agricultural production, and a continual increase, over several years, in the cost to the region resulting from the continual increase in extra-regional food imports.

While Guyana has continued, through the period of the COVID-19 pandemic and a subsequent ‘season’ of severe weather-related flooding of agricultural lands across the country, to hold its own in terms of local agricultural production even as pockets of scarcity of some agricultural commodities have induced price rises, the long-term food security prognosis for a wider Caribbean that is both vulnerable to natural disasters that retard the progress of its agricultural sector leaving it vulnerable to ever rising global food prices is a challenge that remains to be overcome.

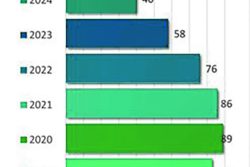

The global picture, from the perspective of the United Nations, would appear to be decidedly grimmer where estimates indicate that between 720 and 811 million people in the world went hungry in 2020 (UN report on the State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World). Going forward the World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that 272 million people are already at serious risk of becoming acutely food-insecure in the countries where it operates. Acute food insecurity is defined as when a person’s life or livelihood is in immediate danger because of lack of food.

Whether or not the fact that the World Bank has moved assertively to throw in its lot with other international partners and governments in an effort to roll back the worst excesses of the crisis will bring about an early change is unclear. The Bank is reportedly working with the aforementioned partners to monitor domestic food and agricultural supply chains, track how the loss of employment and income is impacting people’s ability to buy food, and ensure that food systems continue to function despite the COVID-19 challenges that militate against that process.

The International Development Association (IDA), a World Bank agency that provides material support to the world’s poorest countries, has been pressed into service in an attempt to help alleviate the crisis. Between April and September last year it provided US$5.3 billion in new food security-related commitments through a combination of short-term COVID-19 responses and investments to address the longer-term drivers of food insecurity. Its support initiatives have embraced one Caribbean Community (CARICOM) member country, Haiti, where, through the Resilient Productive Landscape project, it mobilised emergency funding to help over 16,000 farmers access seeds and fertiliser and safeguard production for the next two cropping seasons.