The Cinderella story entered European tradition in the 17th century, but records date back to as early as Egypt BC. The story has had a stranglehold on the creative world for centuries. Which forsaken body has not hoped to live up to the promise of getting its own “Cinderella Story”? Amazon Studios’ “Cinderella” joins a long (long) line of live-action adaptations of the story. Why another “Cinderella”? It’s not an unfair question amidst constant concerns about the state of originality in popular film. But, questions of originality are not really the issues at hand in this “Cinderella”. There are more pressing concerns…

Kay Cannon (most notable for her writing: “30 Rock” and “Pitch Perfect”) writes and directs this new musical “Cinderella”. The (mostly) jukebox musical interpolates a smattering of original songs within a score that’s mostly filled with pop hits of the last few decades. But, from its opening scene, “Cinderella” seems out of sync with its musical intentions. Overhead narration introduces us to this kingdom, bound by tradition for centuries, that was on the verge of change. And with that ominous hook, the strains of Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” begins to play. Out of sync? You bet.

Jackson’s upbeat pop-dance song was a 90s anthem, a call to arms against racial injustice. This opening number is a mash-up of Janet Jackson’s “Rhythm Nation” and Des’ree’s “You Gotta Be”, and it’s an auspicious start. Jackson’s song is an explicitly socially conscious one, the persona singing about an intentional change, “Join voices in protest to social injustice / A generation full of courage, come forth with me.” A minute in, and, “Cinderella” had already lost me. In fairness, it gets better. But it never really gets good.

On a very fundamental level, “Cinderella” feels as if it’s struggling to exist as a movie. 2021 is set to be a banner year for movie musicals, but each time a musical opens I remember how many filmmakers still can’t quite figure out the philosophy of a musical. The incongruity of “Rhythm Nation” is the first of many moments where characters are singing words that make little sense.

Twenty minutes later, Cinderella’s Prince bursts into a cover of Queen’s “Somebody to Love”. Except, the preceding scene, our introduction to the not-so-charming prince, has explicitly told us that this is a man who does not wish to marry, abhors the thought of love, and spends his day gallivanting. When the number opens with an earnest, “I work hard every day of my life,” I winced. He’s not singing because he believes it, he’s singing because he has to. And it’s that level of duty, rather than inspiration, that distinguishes “Cinderella”.

And “Cinderella” feels exasperating, for the very fact that it does not quite understand music. Somewhere between the musical director, the orchestrations and the sound mixing, “Cinderella” sounds incongruous and it feels like a death knell for a film that so desperately wants to burst into song.

The spectre of “Moulin Rouge!” looms over “Cinderella”, in the way it does for most 21st century jukebox musicals, and it’s another reminder that folks still don’t quite understand what makes “Moulin Rouge!” such a specific kind of entity. The world of “Moulin Rouge!” is very distinctly Luhrmann’s vision – the arrangements, the aesthetic, the way the music works within the film is very much in service of that vision. That film takes Madonna, and Rodgers and Hammerstein, and Dolly Parton and ensures that sonically it sounds like notes from a single score.

Jukebox musicals work when the disparate numbers feel like they fit. And in “Cinderella”, they don’t. They could, but the arrangements feel like discrete entities onto themselves. Stop. Camilla Cabello’s Cinderella will sing her original pop ballad. Stop. Idina Menzel sings a raunchy theatrical version of Madonna. Stop. Nicholas Galitzine’s Prince launches into a lacklustre rendition of Queen. Each exists onto themselves, but never as parts of the same score. It gets tiresome after a while.

And it all might be more palatable, but “Cinderella” believed in itself. In line with the film’s self-consciousness about its own myth-making, Cannon seems unwilling to believe in the magic of her own tale. So, Cinderella is hardly forsaken. Instead, she is plucky and intentional and mostly self-actualised. She is also a budding fashion designer who intends to make her own way in life. But it’s here the film is particularly cumbersome. On one hand, Cannon directs Cabello to play up an all-knowing disposition, unfazed by anything. And yet, she tries to eke tension out of a strained relationship with her stepmother Vivian (Idina Menzel). But the arc cannot hold. From scene to scene the relationship changes. In one moment, Vivian is a ruthless termagant. In another, she fears for Cinderella in an oppressive society. In another she’s an ambivalent widow. Cannon wants to make some point about female solidarity, but she also wants to make a fable about a lovely woman who will marry a prince, and she cannot stitch the pieces together.

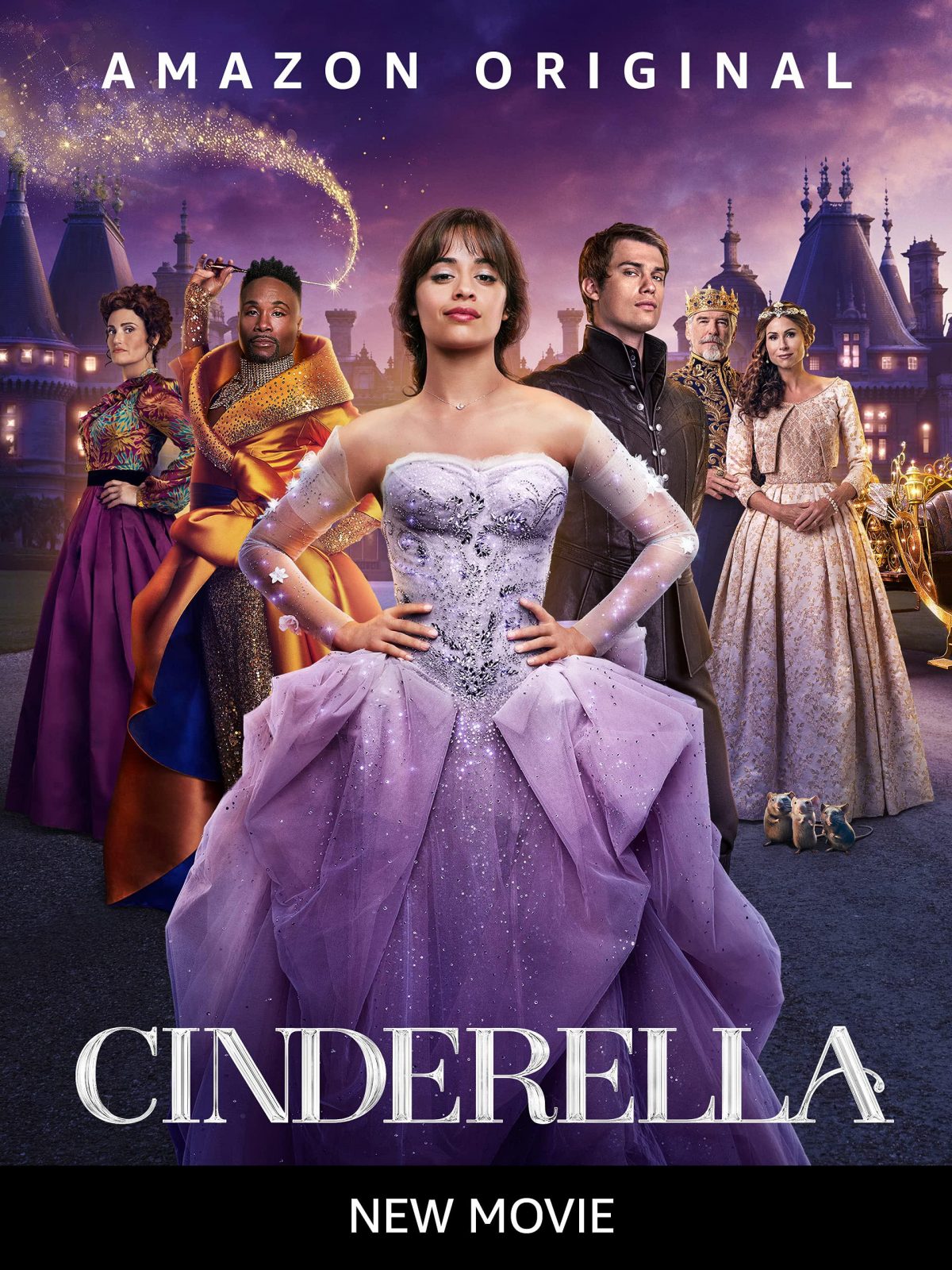

And Camilla Cabello is trying. Often unsuccessfully, but she is trying. But it’s a tall-order for a novice actor to wrangle an insensible role into something coherent. She’s occasionally engaging, particularly opposite Billy Porter as her extravagant Fairy Godparent and Menzel. This is unsurprising. Menzel and Porter are the Tony-Award winning performers, grounding the film in something resembling musicality, and in moments Cabello shows glimmers of promise that would be better served with a director who tends to her possibilities. But any hope is lost because a Cinderella needs a prince, and Nicholas Galitzine is a dull romantic lead. He has neither the grace nor the charm to make the piffle of a story work, and as the centre of Cinderella’s arc, everything comes undone around it.

Fairy-tales exist because they encourage us to stretch our capacity to believe in wondrous, remarkable, unfamiliar, and beautiful things. The remarkable thing is usually buoyed by magic – literal magic — but also the magic of something more philosophical. A magic that distinguishes itself from the prosaic and commonplace. It’s the beauty of the metaphor in the tales, they suggest and allude but very rarely explicate. The message is hidden in the details. But with Cannon, excellent at writing literalisms into jokes on “30 Rock”, the need to explain away any magic, or tension in this world becomes a death knell for “Cinderella”.

Music is like magic. That’s why metaphors are so central to it. Music depends on poetry, not prose. If lyrics were in prose, we would not keep on singing. But, “Cinderella” does not understand music and it does not understand magic. Cinderella’s dressmaking desires could be a window into something creative but even in that arc, Cannon is alarmingly prosaic. Cinderella is not inspired by creativity but by the merely utilitarian. It’s practical and the ultimate resolutions of the tale are telegraphed early on, but it’s not magical and it does not inspire wonder.

“Cinderella” is streaming on PrimeVideo.