Coming from Koriabo, a riverain Warrau community of no more than 200 people at the time “with very limited access to education” in the Mabaruma sub-region, Myra Pierre-Moore, 51, the Learning Resource Development Officer at the National Centre for Educational Resource Development (NCERD) says that as a child she never dreamt she would become the educator and professional she is today.

“I think I have surpassed my dream,” Pierre-Moore told Stabroek Weekend in a recent interview.

Having earned herself a hinterland scholarship at 10 years old to attend Christ Church Secondary School in Georgetown, she said she knew she did not do her best as a student in the city because of cultural shock and the difficulty of adjusting to a new way of life.

As a teacher aide in the Region One community of Koriabo, she said, “I used that opportunity to grow.”

She upgraded herself to qualify for entry to the Cyril Potter College of Education (CPCE), where she graduated as a Grade I Class I teacher. She subsequently headed St Mary’s Primary, the school she initially attended in Koriabo, a Grade E primary school of about 35 children in total, then gained entry to the University of Guyana (UG), where she obtained a Certificate in Education (Cert. Ed. administration) and a Bachelor’s Degree in Education (B. Ed – administration). She acted as Education Supervisor in Region One, was subsequently appointed to the post, then served as Education Officer I in Region One. She was hinterland coordinator in the Ministry of Education while based in Georgetown and pursuing a Master’s Degree in Education, and she is now at NCERD.

When she joined the teaching profession, she told herself she wanted to be more than a teacher aide.

“As teachers, especially as women, we have to try harder. Sometimes we have so much more. Thank God I have a supportive husband. Through hard work, a lot of dedication and investing in myself, I am where I am today. Do not wait for others to do stuff for you. Nobody will. They might point you in a direction. Even at my level, I can still do better. Yes, I still want to obtain a doctorate.”

She is grateful to role models and mentors like teachers Olga Chacon, Bernice Pierre, Yvonne Hercules and Annette Baharally, and former Regional Education Officer (REdO) Lloyd Baharally, who recommended her to do the Ministry of Education (MoE) cadet programme for recruiting young educators. Mentoring is also now a part of Pierre-Moore’s own make up.

About her professional journey, Pierre-Moore, the daughter of Philbert and Hilda Pierre, said, “Thankfully we lived across the river in Saint Creek so we paddled [in dugouts] through the creek and then cross over to the school on the other side of Koriabo River. We played all the games you play. In the mud, with the leaves and in the trees. We played jump rope with vines, gam, marbles, hop scotch, saul call, cricket and rounders.”

On the first day of her secondary education in Georgetown, her older brother, Paul, took her to school and left her in the auditorium because he had to go to his own class in the same school. “He told me where to go but still I felt so lost. I stood there crying. The head prefect, ‘Shawn’ Beckles told me to stop crying. She helped me to find my class, carried me like a baby and put me down in a seat.”

She cried a lot throughout the earlier part of her secondary school years. “I would start to count the weeks and days to return home for the Christmas and August holidays based on how many weeks there were in the school term.”

The hinterland students’ welfare unit, which was at the Amerindian Residence, would host meetings, organise short trips out of town and social events. “These exposures helped me to become more sociable because I was very quiet. We developed a camaraderie, so it was not as bad after that.”

After writing several subjects at the General Certificate of Education and the Caribbean Secondary Education Certificate (CSEC), Pierre-Moore returned to Koriabo. She later learned she had obtained a Grade 4 in English at CSEC. “That was enough for them to appoint me, one year later, at 18 years, a teacher aide at St Mary’s Primary.”

A year later after her appointment, the head teacher, Olga Chacon and the other teacher left the school. Going into 19 years, Pierre-Moore had to take control of St Mary’s. “That is to tell you how dire things were with staffing in hinterland schools in those days. Thankfully Teacher Olga kept meticulous records and after she left I went through them and saw how to write up monthly reports. I had to go to the Department of Education (DoE) meetings at Mabaruma regularly and so I learnt from other heads.”

In the late 1980s, the community had problems with farmlands that were no longer fertile and farmers started taking up new lands at Long Point in Lower Koriabo. “My father was the captain (toshao) of the village at the time and there was a call to relocate the school because people were moving down river. Eventually the school was dismantled. Children were shifted to Arukamai Primary, which was in Upper Koriabo, to Kamwatta and to Wauna. I was moved to Morawhanna Primary.”

In 1989 she was transferred to Mabaruma Primary.

She graduated from CPCE in 1992. At CPCE, she was crowned Campus Queen in 1991, sharing the honour with Campus King, Virgil Harding.

While she was at CPCE, St Mary’s was rebuilt in Lower Koriabo. “I, being young and trained, the DoE offered me the position.” Pierre-Moore did not want to go back to Koriabo. She felt she needed the opportunity to grow in the teaching profession to eventually become a head of a recognised school. Then late educator Bernice Pierre told her to see the appointment as a challenge and as an opportunity to grow. She offered her services and that of the DoE to assist, which changed her mind.

Taking initiative

On her return to St Mary’s, the teachers at Arukamai and Kamwatta, who were untrained, approached her to help them develop their schemes of work and lesson plans. “I started having sessions with them. When the tide was coming down on Saturdays, the Arukamai and Kamwatta teachers would come down the river to my end and we would spend the whole day working. When they knew the tide was going in the other direction, my teachers and I would go upriver to Kamwatta, and the other school would come half way to meet us. We carried our own food.”

She shared her knowledge about multi-grade teaching and the integrated approach to teaching using a thematic approach. In those communities with three teachers in a Grade E school, a teacher would be assigned to Prep A and Prep B, another to teaching the primaries and another, the forms. The schools would have less than 50 students each.

“We were all multi-grade teachers. Out of our chosen theme we would see how we get mathematics, social studies, language and science tied in and then work in other subject areas like health education, physical education and other enrichment subject areas. We were planning every Saturday for the following week.”

When the inspectorate team visited during the first six months of her first year of teaching, they were surprised that the three schools had completed their whole term’s scheme of work. Pierre-Moore explained what had transpired to them.

“They visited the other schools and on their way back they stopped. I felt bad because I thought I had done something wrong.”

They told her they had verified what she had said was true and the teachers and children seemed to be happy with the help she was giving them.

After that visit, she received a letter from the REdO summoning her to the office at Mabaruma the following Tuesday. Tuesdays are market days at Kumaka, Mabaruma, so she travelled with a boat going to the market, apprehensive about what to expect.

The REdO told her she was breaking all the regulations with regards to curriculum and management, she did not consult the DoE about her doings, she changed the school system, did not tell anyone she was visiting other schools and working with other teachers, and changed the way the schemes of work were to be done.

“I apologized. I said I was sorry and was only helping out. I didn’t know I was doing anything wrong and breaking regulations.”

Pierre-Moore said Baharally, the REdO, then congratulated her and told her that the inspectorate team was impressed she had shown initiative by not staying at only the school she was assigned to but was able to help two other schools. He said the feedback from the other teachers were good but they also needed to look at other areas that were left out in the curriculum.

He told her the DoE would work with her but she had to document the work she did on the Saturdays and submit reports about them. He asked her to provide a list of food items they would cook on a Saturday and so they were provided with money to buy food items.

At the end of that year, she was named the most outstanding teacher of the year in Region One because of the initiative she had taken.

Out of the classroom

After two years at St Mary’s, Pierre-Moore was transferred to the DoE and seconded as personnel clerk/administrative assistant and was appointed a supernumerary head for Sacred Heart Primary, a Grade E school in the Aruka River, to improve on the salary she was paid.

In 1999, when the MoE offered the cadet programme for junior educators, Baharally recommended that she apply to join the programme. On graduating from the course, which was held in Georgetown, the same year, she was appointed acting Education Supervisor.

In 2001 she was assigned to the DOE (Georgetown) at 68 Brickdam as an acting Education Supervisor at the primary level along with several others to enable her to start the Cert. Ed. Programme at UG. She graduated in 2003 and continued to pursue the B. Ed programme and graduated in 2005.

After obtaining her Bachelor’s Degree, she returned to Region One and continued to serve in the substantive post of education supervisor. In 2007, she was appointed Education Officer 1 for Region One.

“One of the things I enjoyed as education officer, was facilitating one-week team visits to areas that could not be accessed within a day. We would carry a specialist in either/or nursery, science, social studies, mathematics and work with teachers who were worst in those areas. We would sleep on the desks and benches or tie up hammocks because there were no guest houses. By that weekend the teachers would have gained something to work with until we return again.”

In 2009, the position of hinterland coordinator within the MoE’s Education for All – Fast Track Initiative Programme was advertised. Pierre-Moore applied for the post and was successful.

“When that offer came, I jumped at it because it offered opportunities to not only work with Region One but all of Guyana’s hinterland.”

She was based in Georgetown but the projects were hinterland-based. A lot had to do with improving education, teaching capacity, advising on and monitoring infrastructure and other empowerment programmes like the school feeding, installing community management committees and monitoring and establishing learning resource centres to give support to a cluster of schools.

During her 2009 to 2012 tenure, new resource centres were opened at Wauna and Waramadong. She was in charge of the 20 resources centres in the hinterland. Due to the dire lack of resources, like books, research materials, teaching resources, teaching and learning aids in hinterland schools, through a Department For International Development programme, the MoE provided a quantity of modern equipment like computers, printers, television sets, photocopiers and projectors to some schools and trained teachers to use the new technologies.

When the programme ended in December 2012, Pierre-Moore, who was on secondment as hinterland coordinator was due to return to Region One. She was retained at the MoE as she had just completed her Master’s Degree in Education, which she had been reading for on a government scholarship while being hinterland coordinator.

Going back to Region One with a Master’s Degree was not recommended. This also meant she had to serve the ministry at a higher level. At the time, NCERD had advertised a number of vacancies, including one for a Learning Resource Development Officer.

“The job description included being responsible for learning resource centres, which had been in my line of work and I knew I could continue to assist the same programmes I had started as hinterland coordinator. I applied.”

She was appointed to the post in March 2013 with responsibility for the resources that go from NCERD to schools and resource centres, to visit schools to see what is happening in terms of teaching/learning resource, how and what they use as teaching/learning aids in the teaching instructional period, and to share best practices.

Her job is a collaborative one, working with other departments to ensure that the resources are fully utilised and to see what resources can be developed to put into schools.

She has worked on the Guyana Early Childhood Education Programme with NCERD’s current director Quenita Walrond-Lewis on developing a manual on how teachers could use, among other things, the indigenous materials in the environment they were in.

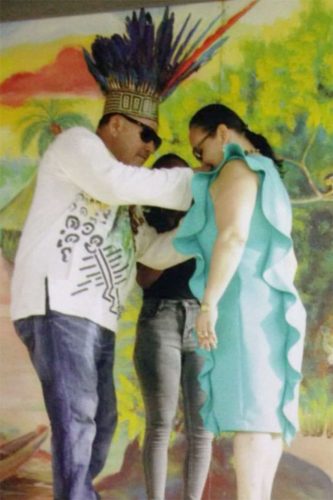

Pierre-Moore was recognised by the former Ministry of Indigenous Peoples Affairs for her service in the field of education.