Elia Kazan’s “A Streetcar Named Desire” premiered at the Venice Film Festival on September 9, 1951. The film would leave an indelible mark on the careers of those involved, and would breathe new life into its already successful source – Tennessee Williams’ 1947 Pulitzer Prize winning play.

But 1951 was a different time for the relationship between drama and film. For example, by 1951 eight of the last ten Pulitzer Prize dramas would be adapted to films within ten years of their premieres. By comparison, in 2021, the most recent Pulitzer Prize winner to be adapted to film was John Wells’ 2013 adaptation of Tracy Lett’s 2008 work “August: Osage County”.

The link between “Streetcar” on stage and on screen was emphatic, though. Williams would write the adaptation of the script, Elia Kazan – the director of the Broadway premiere – would direct and three of the four principal cast members from the Broadway production would return for the big screen (Karl Malden as Joe, Kim Hunter as Stella, and Marlon Brando smouldering to his breakout role as Stanley Kowalski). Tony-Award winning American actress Jessica Tandy would be replaced by British actress Vivien Leigh, who played the central role of Blanche DuBois in the play’s 1949 London premiere.

Like many literary adaptations of that era, the cinematic “Streetcar” has been inextricably linked to the original text itself, and the presence of Williams – playwright and screenwriter – in both has only emphasised this. As we celebrate its seventieth anniversary, it is useful to consider the dual legacy of Leigh’s Blanche DuBois, and the “Streetcar” she rides in on. There will be more Blanches to come but at sixty-years the cinematic “Streetcar” continues to feel moving and necessary because of its empathy and understanding of this complicated woman. Blanche, a former Southern belle experiencing a series of debilitating losses, has endured as a legendary figure of the stage and the screen. If Shakespeare’s Hamlet is the role for all male thespians, Blanche is figure of the 20th century that feels as momentous for women. Her tragic downfall has felt familiar, and reverberated in tragedies onscreen and onstage in the decades since her conception.

The story is straightforward – a contemporary tragedy of a woman whose fate leads her to all the wrong places. A down-on-her-luck Blanche, penniless and forsaken, arrives on the doorstep of her sister and brother-in-law, feigning strength. Her sister is enthused at the visit, her brother-in-law less so, especially as the visit seems permanent. Blanche needles at the cracks in their marriage, and a resentful Stanley begins to dig into her past, revealing Blanche’s own cracks to tragic results. Stanley’s relentless pursuit to investigate Blanche has become indicative of an inherent salt-of-the-earth practicality, against Blanche’s own fantastical world of illusions, but “Streetcar” gains its power from the way that it depends on the overlap between what feels real and what feels illusive. It is a story that lives in incongruous and paradoxical.

There’s a striking moment near the opening of the film that announces this. Blanche emerges, after a brief prelude, at the beginning through a cloud of mist. It’s an evocative moment that becomes instructive for the ways it suggests what is to come. The mist feels redolent of literary traditions, except this mist is not natural but the polluted smoke from the rundown streetcar that delivers Blanche to New Orleans, and to her fate. It’s such a specific moment of truth and illusion. The paradoxes are central, to the image, to the film and – critically – to Leigh’s performance of the role. Leigh had already played an iconic Southern belle twelve years earlier in “Gone with the Wind”. But, Blanche’s fragility feels, ostensibly, like a direct repudiation of her Scarlet O’Hara, who was tough and loud and wrong. Except, Blanche is strong and weak, wily and out-of-her-depth.

We are all paradoxes, though. It’s the paradox that make the performance, and the film. Truth and illusion merged to dramatic effect.

“Streetcar” is an excellent play, and feels vivid and affecting on stage decades after its premiere. But there’s something that feels profoundly camera-ready about it. Williams has always been preoccupied with characters lying to themselves. But in “Streetcar,” the lies are internal but also explicitly visualised. In one of the play’s climaxes, Blanche’s would-be-lover rips a paper-lantern off a naked bulb and turns it on– illuminating the screen. As he drags her beneath the bulb and into the light – the moment feels made for film – Leigh’s distraught face envelopes the screen.

What Kazan and Leigh and company get so right is the complicated nature of Blanche that avoids flatter ideas of her characterisation as one that is all-fantasy against the other characters’ truths. And it’s right there in one of the play’s most memorable moments. Before Mitch reveals the light, Blanche cries out to him, “I don’t want realism, I want magic!” It’s a vivid line that’s often been misconstrued. It’s not the truth that Blanche abhors, it’s the mode of delivery. Her issue is with realism and not with reality. Her escape is a choice. And it’s imperative that the play confronts each of the characters’ decisions to conjure their own images of the world. If generation after generation has wrestled with lust for Brando’s Stanley – a sinewy figure that the camera asks us to covet – Kazan and Brando do well to emphasise his own weaknesses. As written, and especially as performed, his most searing moments are the ones where he is intentional about what versions of events he wishes to hold on to –desperate pleas for his Stella that seem like their own fantasies, insisting that everything was better before Blanche’s interruption.

But they’re all lying to themselves and they’re all living in their fantasies. But, that’s Tennessee Williams’ praxis. Years later, Williams would say of Blanche, “[She] was the most rational of all the characters I’ve created and, in almost all ways, she was the strongest.” It’s an intriguing claim when measured against the legend of her that has persisted which Kazan’s “Streetcar” elides, and complicates. My early love for film, and theatre, began with an affinity for Tennessee Williams, whose empathy for his most broken characters has always been stirring. The moral greyness that his contemporary writers treated as unfortunate transgressions, have always felt like noble elisions for him.

As written, Blanche is described as five years older than her sister Stella, who is in her mid-twenties. She girlishly pretends she is the younger sister, fearing that she has aged out of being desirable. At 38, Leigh was almost a decade older than both Brando and Hunter. Critically, Leigh and Hunter look closer in age than the gap – but as the years have gone by, the gaps between Blanche and the couple she interrupts has deepened. In the 1984 TV version, the ten-year gap remained. In the 1995 version, there was a 16-year gap between the sisters. Stage revivals have followed suit. A critically acclaimed Australian production with Cate Blanchett and a similarly acclaimed London version with Rachel Weisz featured a twelve-year gap. And a recent Young Vic revival with Gillian Anderson featured a 20-year gap. The Anderson version has recently enjoyed a digital release, and feels like a too familiar imagining of Blanche that loses the sensitivity of Williams’ play, Kazan’s film and Leigh’s empathy.

Too many later interpretations of Blanche have presented her as that barracuda, purring like a grotesque kind of Medusa ready to entrap her victims. It’s the central conceit of Anderson’s interpretation. Her Blanche is costumed and made-up to emphasise that discrepancy in age, strutting in ostentation beside the lived-in diffidence of Vanessa Kirby’s Stella. It’s a discrepancy that feels

incongruous with the text, but more importantly it feels like a betrayal of Blanche herself. Blanche’s tragedy is that a mere woman of thirty is convinced her life is over. Thinking of Leigh’s work all these decades later feels like a valuable course-corrector in successive ideas of Blanche, a woman that Kazan holds tenderly. But, in thinking about Leigh’s Blanche on this anniversary I hearken back to the original Blanche on stage, Jessica Tandy.

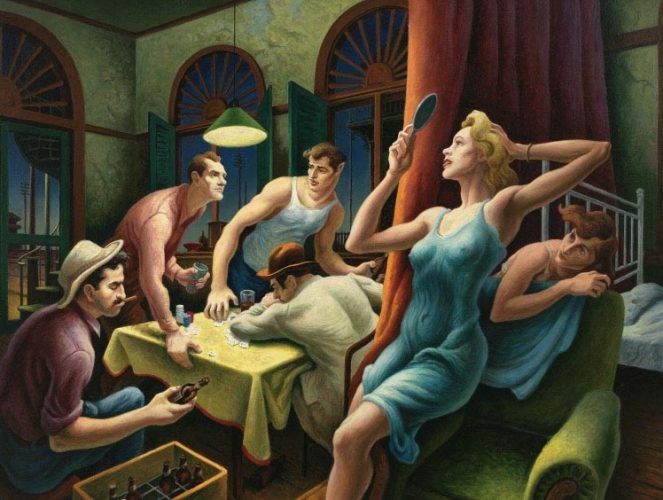

In 1947, fresh off its successful stage premiere, Thomas Hart Benton was commissioned by David O. Selznick to create a painting from the poker night sequence in the play – later recreated in the film in one of its best scenes. In the painting, the men play poker as a distracted Mitch has all eyes on Blanche who preens beneath the light as Stella cowers behind her, in a transparent bodice. It’s a rich painting, but it’s all wrong for the play. The producers were so excited by the commission, they asked the cast to pose for a recreation. Tandy refused, and her refusal was summed up as her doubt as to the painting’s almost naked rendition of Blanche.

She explained her refusal, though, in a letter of decisive critical perception. I include a section here: “Eight times a week […] I have to make clear Blanche’s intricate and complex character…her background…her pathetic elegance…her indomitable spirit…her innate tenderness and honesty…her untruthfulness or manipulation of the truth…her inevitable tragedy. I share your [Tennessee’s] admiration for Benton as a painter, but in the painting, he has chosen to paint, it seems to me the Stanley side of the picture.” I think about that defence of Blanche a lot. It teems with an understanding of the character, and lucky for us – even though Tandy did not reprise the role on film, Leigh’s interpretation, unlike some that came after, remembers that.

I’ve always wondered what a film version of Tandy’s Blanche might look like, although Leigh’s interpretation is one for the ages. It remains the definitive Blanche not only because it’s on screen, though, but like her predecessor – Tandy – she played an image of Blanche that was not Stanley’s. As Blanche DuBois has grown from icon to legend, the memory and idea of her has become that of Stanley’s – an ageing woman, preening for attention and desperate for it. But that’s not really her. She is incongruous; she is a paradox. But she is also a part of a dwindling group holding on to the beauty of illusion.

It’s a reason the character has remained so fascinating. In her “pathetic elegance”, she invites our understanding and our empathy. When Blanche leaves the play, announcing her infamous dependence on “the kindness of strangers”, it feels like an invocation of the film’s legacy. A broken woman depending on future generations to treat her with care. I don’t know if the world has done right by the legacy of Blanche, but Kazan and Leigh’s interpretation feels like a living document that keeps the core of Blanche alive in the best of ways. Kazan’s and Leigh’s recreation of Blanche is a treasure for the way it sees through the paradox and finds something tender and moving.

“A Streetcar Named Desire” is available on HBO Max, Prime Video and other streaming services.