I

I walk through the long schoolroom questioning;

A kind old nun in a white hood replies;

The children learn to cipher and to sing,

To study reading-books and history,

To cut and sew, be neat in everything

In the best modern way—the children’s eyes

In momentary wonder stare upon

A sixty-year-old smiling public man.

II

I dream of a Ledaean body, bent

Above a sinking fire, a tale that she

Told of a harsh reproof, or trivial event

That changed some childish day to tragedy—

Told, and it seemed that our two natures blent

Into a sphere from youthful sympathy,

Or else, to alter Plato’s parable,

Into the yolk and white of the one shell.

III

And thinking of that fit of grief or rage

I look upon one child or t’other there

And wonder if she stood so at that age—

For even daughters of the swan can share

Something of every paddler’s heritage—

And had that colour upon cheek or hair,

And thereupon my heart is driven wild:

She stands before me as a living child.

IV

Her present image floats into the mind—

Did Quattrocento finger fashion it

Hollow of cheek as though it drank the wind

And took a mess of shadows for its meat?

And I though never of Ledaean kind

Had pretty plumage once—enough of that,

Better to smile on all that smile, and show

There is a comfortable kind of old scarecrow.

V

What youthful mother, a shape upon her lap

Honey of generation had betrayed,

And that must sleep, shriek, struggle to escape

As recollection or the drug decide,

Would think her son, did she but see that shape

With sixty or more winters on its head,

A compensation for the pang of his birth,

Or the uncertainty of his setting forth?

VI

Plato thought nature but a spume that plays

Upon a ghostly paradigm of things;

Soldier Aristotle played the taws

Upon the bottom of a king of kings;

World-famous golden-thighed Pythagoras

Fingered upon a fiddle-stick or strings

What a star sang and careless Muses heard:

Old clothes upon old sticks to scare a bird.

VII

Both nuns and mothers worship images,

But those the candles light are not as those

That animate a mother’s reveries,

But keep a marble or a bronze repose.

And yet they too break hearts—O Presences

That passion, piety or affection knows,

And that all heavenly glory symbolise—

O self-born mockers of man’s enterprise;

VIII

Labour is blossoming or dancing where

The body is not bruised to pleasure soul,

Nor beauty born out of its own despair,

Nor blear-eyed wisdom out of midnight oil.

O chestnut tree, great rooted blossomer,

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, O brightening glance,

How can we know the dancer from the dance?

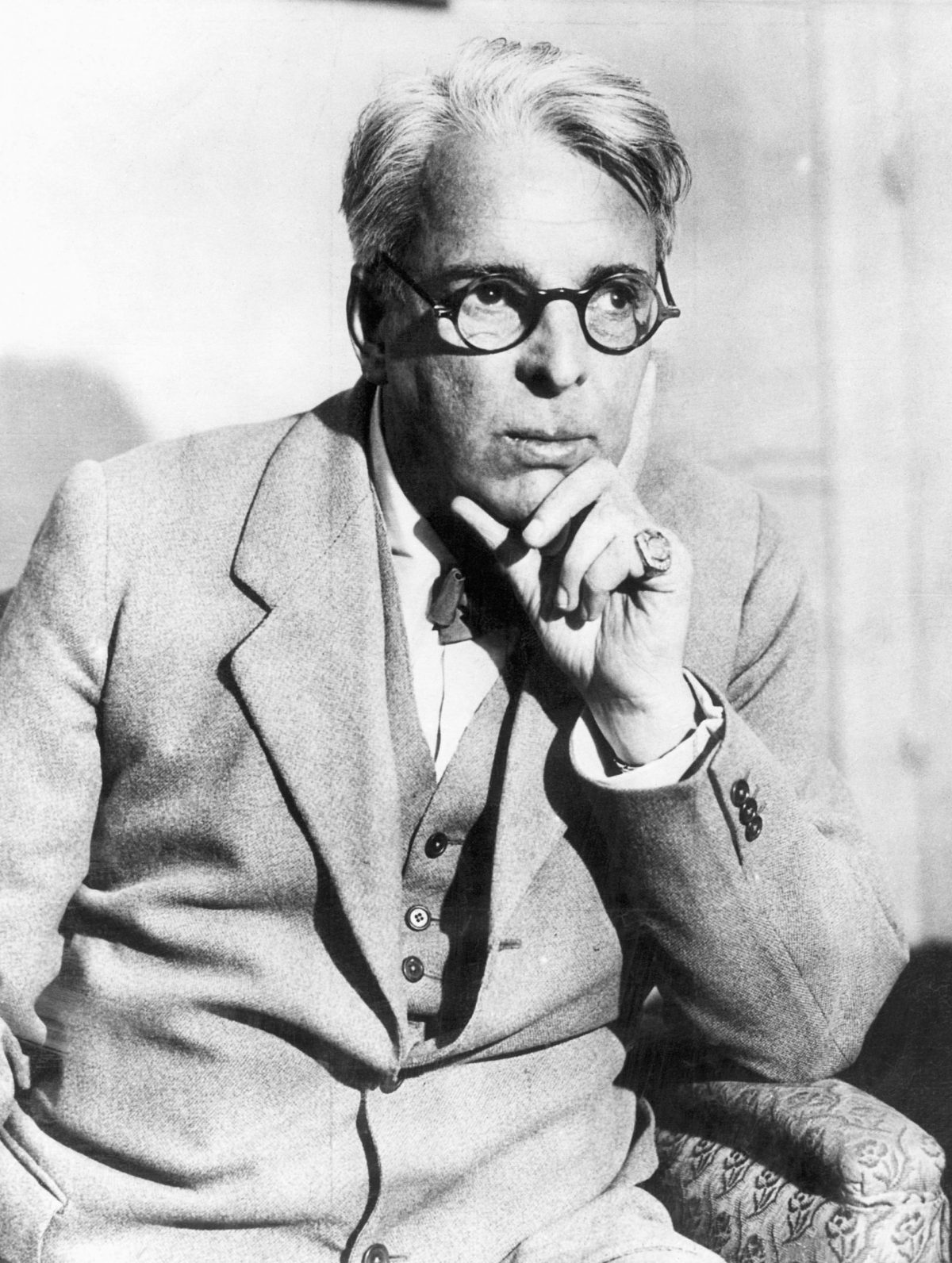

WB Yeats

“Among School Children” by William Butler Yeats is one of the outstanding poems in English of the twentieth Century. It is a poem that defines poetry itself.

One can sometimes find poems that are so influential that they make an everlasting impact on literature. Perhaps the most outstanding is “The Waste Land” by TS Eliot, which, in 1922 utterly changed the face of poetry in English, to the point where it is described as the most influential (or the greatest) poem of the twentieth century.

Eliot’s poem, when it was published in 1922, announced the arrival of modern poetry. To be more precise, it ushered in Modernist Verse, and the departure from the older order of verse and what constituted poetry. Eliot, influenced, it was said, by Ezra Pound, advanced this, and Yeats was a part of that movement. He published “Among School Children” in 1928.

Yet, there are other reasons for highlighting and presenting this poem. It is known that Yeats was among the most favourite of Guyana’s great poet Martin Carter. It is further reported that Carter declared Yeats’ “Among School Children” to be the best poem ever written. That is indeed high praise coming from such an artist as Carter, but it is the kind of declaration that critics would hesitate to make. Carter was forthright on the matter.

Among the most priceless records in the background and development of Guyanese modern literature and culture are the anecdotes told by some prominent personalities who were friends of Carter and protagonists in many literary events. The late David de Caires, attorney at law, former editor of the New World Quarterly and editor-in-chief of the Stabroek News, told tales of poetry readings and literary discussions.

There are records that similar sessions took place in Georgetown as early as the 1940s when Edgar Mittelholzer was involved. They continued through the 1960s into the 1970s and beyond and included Miles Fitzpatrick and Rupert Roopnaraine.

Ian McDonald most recently provided narratives out of these sessions during which poems were read, there were intellectual discourses and the consistent flow of rum. (Rum was a constant in Mittelholzer’s time and he commented on it satirically). McDonald, in the Sunday Stabroek, stressed the love of poetry among participants, but chiefly the reverence with which it was held by Carter.

In a moving narrative, he related how Carter would call for a reading of “Among School Children”, how he would listen in silence with tears filling his eyes. Poetry has experienced no greater love. In particular, Part VIII, the final stanza of this poem, quoted at different times by McDonald and de Caires, one has to agree, is among the most moving closing lines in modern poetry.

“O chestnut tree . . .

Are you the leaf, the blossom or the bole?

O body swayed to music, . . .

How can we know the dancer from the dance?”

Yeats (1865 – 1939) was an Irish poet, winner of the Nobel Prize in 1923, who became quite involved in the Irish liberation wars, and eventually was a Senator between 1922- 1928). Among his duties was the inspection of schools, and this poem was inspired by a visit to a Roman Catholic school in 1926. At that time, Yeats was beginning to reflect on age and youth, the relationships between them, and the future of the youth in the current society.

He explored these in a very neat, well structured poem with an easy rhythm, driven by casual rhyme and the narrative of a 60-year-old inspector of schools reflecting on the wide philosophical concerns because he was driven to reflect on his own youth and the prospects for the school children when they got to his age. He reflected on differences and similarities, dislocation and unity.

These thoughts also drove the poet to classical and mythological references, including his confrontation with Platonic theory. Man used to exist as a complete round being, but Zeus split him into two halves, because, as a whole, Zeus found he was too powerful. Since then, man has been seeking his other half and if he acquires it, he would achieve the completeness of Platonic love. That is why the poet in the final stanza reflected on the whole as against the sum of its parts. He expressed this in the most beautiful poetry.

Further, Greek mythology was explored in the reference to Leda who, while bathing in a lake, was raped by Zeus in the disguise of a swan. The poem is rich with these qualities of metaphor and myth and these, no doubt, appealed to Carter.

This kind of high quality poetry equates with the majesty and might of the great chestnut tree; no need to break it down into its various beautiful parts. Similarly, in the enthrallment of a powerful performance one would not wish to distinguish the dancer from the dance.