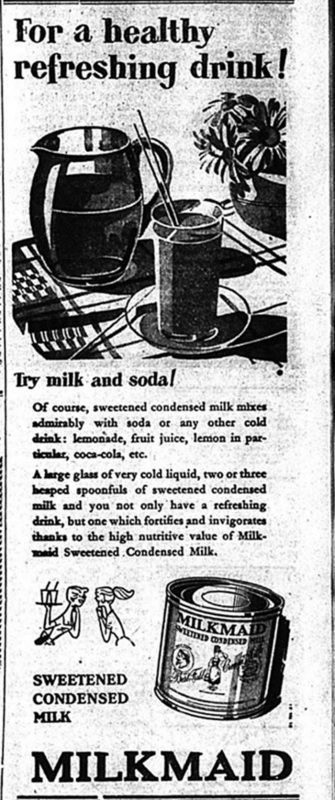

Beverage mixing has been a tradition in Guyana. In 1924, Gaston Smith, the U.S. consul in Georgetown, described bub, a popular mixed drink. This nonalcoholic beverage was “made of milk in which is placed a small quantity of crushed ice and some flavoring.” It was sold in glasses rather than bottles at about 2₵ per pint in bub shops or at street corners. A 1959 newspaper advertisement promoted another nonalcoholic milk-based beverage. Milkmaid Sweetened Condensed Milk was mixed with soda to create a “healthy refreshing drink.” Other milk-based mixed drinks from around the mid-20th century include the various “floats” that were available at the few early soda fountains.

Beverage mixing has been a tradition in Guyana. In 1924, Gaston Smith, the U.S. consul in Georgetown, described bub, a popular mixed drink. This nonalcoholic beverage was “made of milk in which is placed a small quantity of crushed ice and some flavoring.” It was sold in glasses rather than bottles at about 2₵ per pint in bub shops or at street corners. A 1959 newspaper advertisement promoted another nonalcoholic milk-based beverage. Milkmaid Sweetened Condensed Milk was mixed with soda to create a “healthy refreshing drink.” Other milk-based mixed drinks from around the mid-20th century include the various “floats” that were available at the few early soda fountains.

An even earlier mix must have been the mauby–small-lemonade mix. In the late 1950s and early 1960s, the Mount Eagle cakeshop–parlor at the North Road–Wellington Street intersection was known for this mix. The lemonade, which was produced by the Virtue Soda Factory, was bottled with a floating ball stopper, hence the term “marble lemonade.” The factory, located opposite the Mount Eagle cakeshop, was owned by the De Ryck family. The mauby–small-lemonade mix was an exquisite thirst quencher. It remains in the memory of a generation of Guyanese, primarily male, for whom the cinema was the dominant location for leisure and recreation during the 1950s and 1960s. During that era, society frowned upon women drinking mauby or any other brew in cakeshops.

Mount Eagle was one of the cakeshop–parlors in a Georgetown neighborhood with heavy pedestrian traffic and four cinemas: Globe, Astor, Metropole, and Strand De Luxe. These cinemas offered at least three shows per day (1 p.m., 5 p.m., and 8 p.m.) Monday through Saturday. On Sundays, there were typically only two showtimes: 5 p.m. and 8 p.m. On some Saturdays and most public holidays, there was a 9 a.m. show.

Many thirsty people visited the Mount Eagle cakeshop to consume the low-cost mix. It was cheaper than those from the new franchised sweet-drink brands. Many young men went to Mount Eagle because of its “roots cred.” It was a place to get a refreshing drink to quench your thirst in hot and humid Georgetown. Mount Eagle and its product, the mauby–marble-lemonade mix, represented an important innovation in the country’s food and beverage culture. It was a fusion of the old and the new. For me, it became the yardstick for assessing the flavors of the mauby concoctions in Guyana and its diaspora.

I recall the mauby–marble-lemonade mix being served in a glass similar in size to a pint glass in a London pub. In this glass were placed a few chunks of ice chipped from the block of ice located close to the gauze-covered mauby containers. Mount Eagle’s outstanding mauby was made from scratch rather than concentrate. It was “set,” and it ripened with a “magnificent” foam. It had a subtle fizz from the natural fermentation. It had fleeting notes of cloves, cinnamon, orange peel, and other aromatics. About half of the glass was filled with Mount Eagle’s mauby. To this were poured the contents of a marble lemonade, i.e., about 6 oz of a top-quality lemonade. The lemon oils and other flavors in the lemonade amplified the complex flavors already present in the mauby. The carbon dioxide in the lemonade also enhanced the subtle fizz of the ripened mauby.

The routine around the consumption of the mauby–marble-lemonade mix at Mount Eagle included agitating the mix. The tendency was to use the right index finger to blend the flavors and swirl the ice chunks to cool the mix. The customer then tended to suck that index finger before taking the first sip of the “magical” brew. As previously mentioned, the prevailing social norms meant that the participants in this public consumption of non-alcoholic beverages were primarily men.

There was an even older tradition of alcohol-based mixed drinks. Over time, the carbonated beverage bottling companies ventured into this market. According to Henry Kirke, a colonial magistrate resident in British Guiana between 1872 and 1887, a popular ruling class response to the challenge of perpetual thirst from the heat and humidity was the swizzle. This alcoholic beverage required a few simple ingredients and fine blending techniques:

[A] small glass of Hollands, ditto of water, half a teaspoonful of Augostura [sic] bitters, a small quantity of syrup or powdered white sugar, with crushed ice ab libitum; this concoction is whipped up by a swizzle-stick twirled rapidly between the palms of the hand until the ice is melted, and the liquid is like foaming pink cream, to be swallowed at one draught and repeated quantum suff.

As Kirke noted, the swizzle was potent:

In the swizzle, the potency is so skillfully veiled that the unsuspecting imbiber never discovers he is taking anything stronger than milk, until he finds that his head is going around, and that the road seems to be rising up and trying to slap him in the face.

These swizzles established Guyana’s tradition of alcohol-based mixed drinks, including the use of carbonated beverages as mixes or “chasers.”

Chasers: The Early Carbonated Mixers

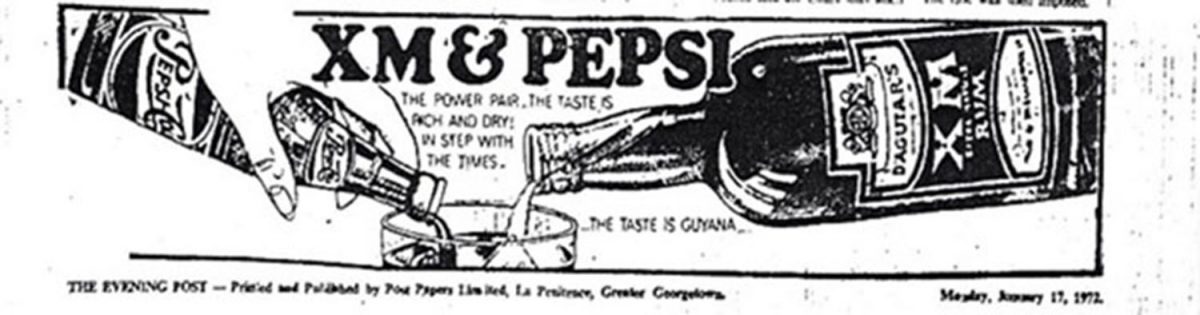

Prominent in the Guyana sweet-drink tradition are small drinks. Approximately 6.5 oz, they are about the size of a small lemonade. Wieting & Richter’s CSID sold the Star brand, and DIH sold the Club brand. Soda water, ginger ale, lime ricky, and tonic water, which were the predominant flavors, were among the earliest carbonated beverages bottled in Guyana. They are associated with the following perennial classics: scotch and soda, rum and ginger, gin and lime, and gin and tonic. These mixes were popular in the private clubs and hotels patronized by the ruling class in urban centers and the staff clubs used by the management of the sugar estates during the early 20th century. World War II introduced rum and Coke. It was also sold in small 6.5 oz bottles. By 1972, Banks DIH was promoting XM rum and Pepsi.

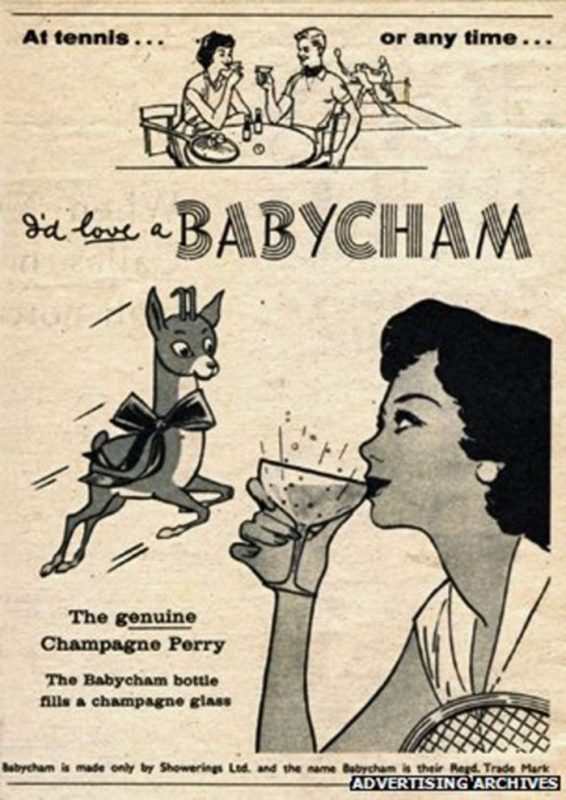

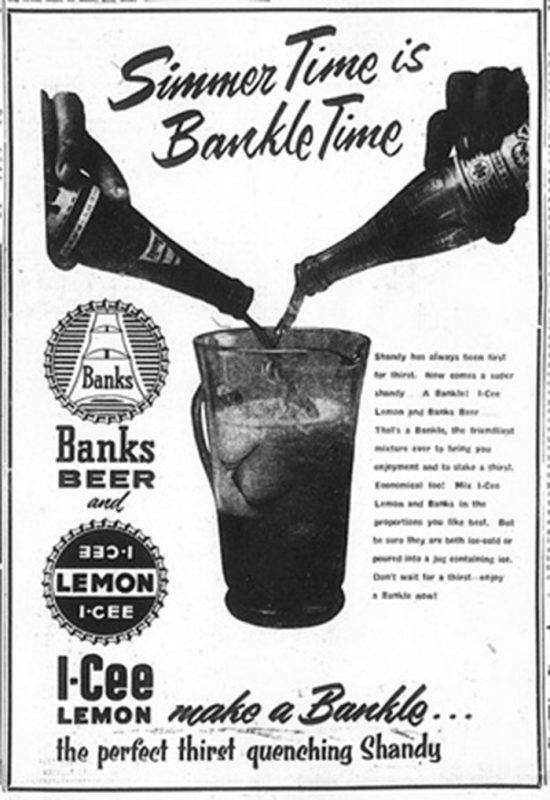

Already present in the colonial drinking culture were shandy and the alcopop Babycham. Developed in British pubs, shandy was a mix of lager beer and lime or lemon–lime juice. So, it was not surprising that after the launch of Banks Breweries, which sold a lager-like brew, a Banks Beer-based shandy mix was promoted. The first reference to Bankle, a beer–I-CEE lemon mix “liked by Mr. D’Aguiar,” was found in a 1961 advertisement.

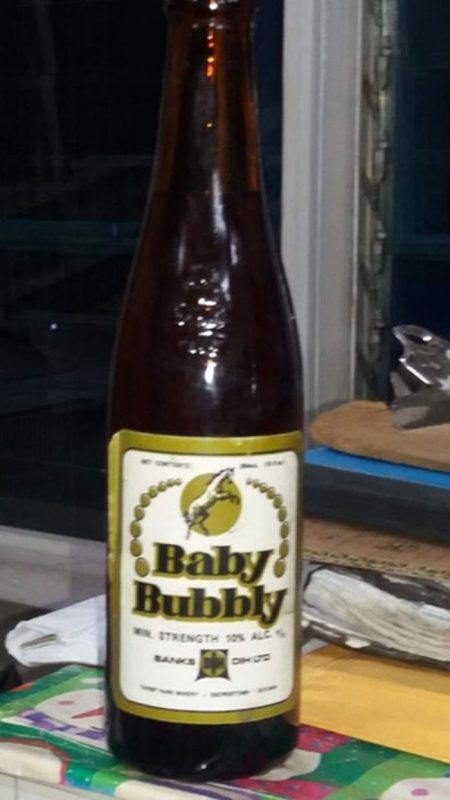

In time, Bankle became the Banks DIH Shandy (1.6% alcohol) line. Baby Bubbly was launched in 1980 to replace Babycham (a 6% alcohol perry), the popular import from the United Kingdom during the 1950s and 1960s. It was one of the first alcoholic beverages in the United Kingdom to target women. This represented a shift in social norms in the UK and British Guiana. Women began to drink alcohol in public. And when they did, Babycham was the beverage. Babycham was evocative of champagne, and the recommended vessel was the champagne glass. Babycham was hip!

Baby Bubbly was one of the innovations that emerged from the mid-1970s economic downturn. According to a June 16, 2020, Facebook conversation on the “Vintage Guyana—History Preservation” page, Baby Bubbly, which was packaged in “an emerald-green glass 10 oz non-returnable bottle,” was on the market for “just a couple of years.” The beverage quickly garnered a reputation for rapidly inducing inebriation. According to the posts, there were rumors that it contained “illicit drugs.” Carlton Joao, Banks DIH’s sales and marketing executive, rebutted those claims. He stated:

For the record, Banks DIH Limited has never acquired, stored nor applied any illicit ingredients to any of its products. Baby Bubbly (no relation to any other Bubbly ever made) was a product developed using indigenous materials during a period of difficult ForEx [foreign exchange] in Guyana. It was crafted as a local Champagne alternative. The product was basically 9% Banko rice wine with carbon dioxide in a 10 oz. bottle.

There were two issues with this … The high level of CO2 carried the high alcohol content very quickly to the brain (much like Champagne would) and had a delayed but significant effect. The second problem was that most felt that it was a single-serve product and downed the whole bottle. Well, we all know how that ended. It was discontinued as a result of its reputation. Rather unfortunate.

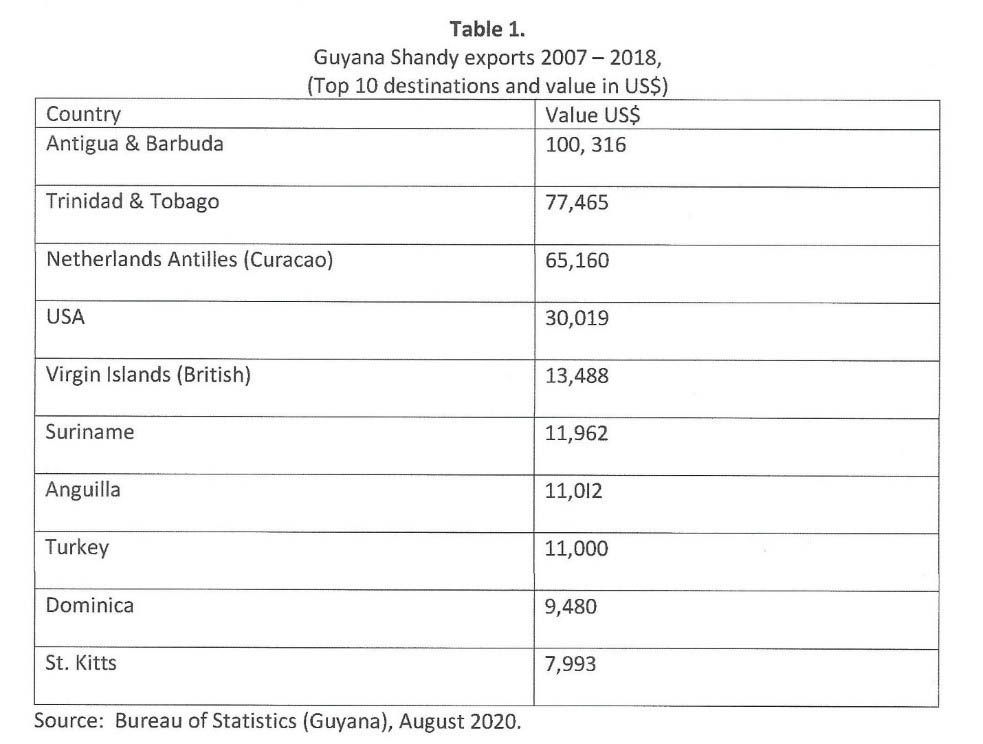

Banks DIH’s Shandy has been available in five flavors: sorrel, pomegranate, honey lemon, citrus punch, and champagne. In 2019, the sorrel and champagne flavors won the Monde Selection 2019 Gold Award for Quality. Between 2007 and 2018, shandy exports to the Caribbean, North America, and Europe exceeded US$330,000. Table 1 shows the top 10 Shandy markets and the value of those exports from 2007 to 2018.

Shandy was not the only alcopop available in Guyana in June 2021. Smirnoff and other imported coolers were also sold.

Selected References

Heydorn, B. “Before my memory fizzles, recall Guyana’s soda fountains.” Indo Caribbean World, April 2, 2008 at: http://www.indocaribbeanworld.com/archives/2008/april_2_2008/arts.htm

Kirk. H. Twenty-Five Years in British Guiana. Westport, CT: Negro Universities Press, 1970.

Carlton Joao, Facebook comment, July 6, 2020.

Carlton Joao, Ibid. https://www.facebook.com/VintageGuiana/posts/892808027888777

Vintage Guyana-History Preservation. June 17, 2020. 10:20 pm. https://www.facebook.com/VintageGuiana/posts/892808027888777

BBC. How Babycham changed British drinking habits. Available online at: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-25302633?fbclid=IwAR1QR3XDpsViGc6DyzPowhXGnvgQ5uaYZ4lAVGInoqTEjRmb2JAgiczIGGc © Vibert C. Cambridge, 2021