by Ryan Persadie and Natasha Ramoutar

Ryan Persadie is an artist, educator, and writer based in Toronto, Canada. Currently, he is a PhD candidate in Women and Gender Studies and Sexual Diversity Studies where his research interrogates relationships between queer Indo-Caribbean diasporas, Caribbean feminisms, and legacies of indenture within archives of performance, embodiment, and popular culture.

Natasha Ramoutar is a writer of Indo-Guyanese descent from Toronto, Canada.

Defying chronological time, the reader comes to explore Mohabir’s lessons through traces of prose, poetry and song that criss-cross history and space via intersecting, but often conflicting cultural and (trans)national politics. Perhaps the most revealing way he works through this is by speaking to his queerness. Through a hauntingly, and consequently, distinctly Caribbean approach, his queer Indo-Caribbean sexuality is brought together through fragments, traces, and glimmers of a sexual practice that defies Euro-American notions of public disclosure and against heteronormative Caribbean rules of a respectable “East Indian” masculinity, and emerging idealistic dulahahood.

While spending much of his time tracing the routes of his diasporic experience without overt mention of sexuality, the pieces of Mohabir’s queerness that he layers together come to speak a transgressive language all of their own. In doing so, he simultaneously defies mainstream tropes and representations of queer masculinity in the Global North by rejecting normative identity terms such as “gay”, or “out of the closet”. Instead, he opts to use a term more-often-than-not positioned within the realm of the pejorative, oppressive, and violent in Guyana and the Guyanese diaspora: the Antiman.

Mohabir’s tracing of the Antiman figure requires multiple forms of language to speak. Similar to the ways in which queerness operates outside the linear, the singular, and normative, fragments of Indo-Caribbean voice sweep in and out of his memoir, each providing their own grammar to speak to his felt experience. Reconciling a queer Creole form all of their own, the language Antiman evokes becomes central to translating his queerness in this text. Simultaneously, Antiman works against dominant homophobic ideologies in the Caribbean and its diasporas that often separate queer sexuality from mainstream ideas of Caribbean masculinity and belonging. In addition, the Antiman is spoken through tongues of Bhojpuri, Creole, American Standard English, chutney, and across multiple geographies such as the plantation, Hindi language classes, Florida, the New York City subway line, Ontario (Canada), Liberty Avenue, and rural Guyana as they merge with one another to produce his queer Indo-Caribbeanness in new hybridized poetic forms. In his text, the Antiman becomes a site of important and critical queer Indo-Caribbean speaking, living, and being that does not have to live solely in the realm of the damaged, hurt, and wounded.

Instead, such language, perhaps what we can call an “anti(man) poetics”, provides the reader with pieces of Mohabir’s explorations of home/land, (non-)belonging, masculinity, coolieness, spirituality, family, and violence. The inherent queer quality of these poetics is directly rooted in the crossing of geography, history, and memory that Mohabir quilts together through the chosen vignettes he expresses in each section of the text; a genre made possible through such processes of fracture. However, unlike many historical and dominant discussions of Indo-Caribbean arrival in the Caribbean – following in line with writers such as V. S. Naipaul that has argued that Indo-Caribbean forced migration and consequential dislocation from “Mother India” has rendered Indo-Caribbean life as always inauthentic and damaged – Antiman steers us away from attachments of Indo-Caribbean experience to ever-present identity death. Instead he reorients us towards existing and new sites of queer Indo-Caribbean re-birthing, re-making, and re-assertion.

Anti-man poetics also move through central characters and bodies Mohabir references in the text, reframing important relation-ships that provided him with the knowledge base to understand his racialized queer sexuality. In a chapter entitled “Open the Door”, Mohabir first introduces his sexual difference not through coming to terms with his same-sex desires, but by first understanding the difference his Aji presented towards representations of normative South Asian identity and that of conventional white femininity. He describes her language early in his life through what a Eurocentric audience would denote as “brokenness”. In doing so, he explains the syncretized forms of Caribbean Hindustani and Creole that would mix and re-mix with each other in her stories and songs to him. In another moment, he notes that “she did not speak film Hindi… but rather some other language that had been broken on the plantation” and that her English was “a Creolized version that would never count as literary.”

Instead of accepting this problematic description, Mohabir chooses to record his Aji’s songs and transcribe them, valuing them as cultural artifacts. The linguistic cross-roads that his Aji offered was never “broken” to him or in need of colonial recuperation, despite what forces of power would have him believe. Instead, the cross-roads of experience Aji lived through – her grammar, songs, and stories – became the exact know-ledge center by which Mohabir comes to understand brokenness as a distinct site of queer Indo-Caribbean identity, power, and reclamation.

Furthermore, Mohabir traces his queer lineage through language, and his Aji’s songs thus serve as a connection to the past. Her oral storytelling, which he describes as “forged against the anvil of indenture on sugar cane plantations,” acts as a means of retaining that history. Since she was the last speaker of Guyanese Bhojpuri in their family, he was compelled to record her stories and songs since they were “on the verge of being erased forever.” His Aji becomes a central figure in the memoir as a living, breathing archive. This serves as the backbone for the hybrid memoir – an anchor that Mohabir returns to when thinking about contemporary Indo-Caribbean race, sexuality, and culture.

If Mohabir’s queer Indo-Caribbeanness is explored via fragmentation, it’s to remake and reassert his place not only within the literary landscape, but in the historical and contemporary archives themselves. Such fragments do not require wholeness or fixing, but speak through their distorting and unruly forms. We see this throughout the text in the poems, narratives, and sounds that Mohabir weaves, inserting his own story in verse alongside his Aji’s songs. By using similar literary techniques and incorporating his own experiences, Mohabir reinvents a genre of queer Indo-Caribbean liveability that continues to be in conversation with these historical archives.

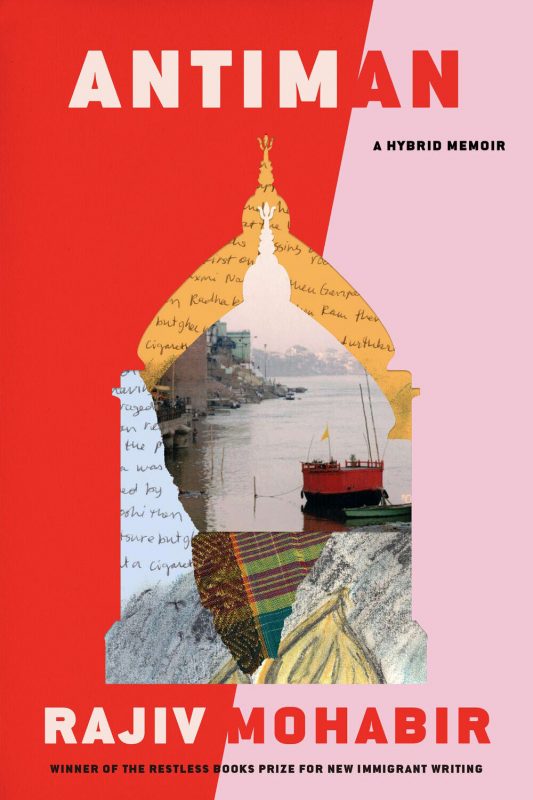

Similar to the collage that graces the cover of the book, this hybrid memoir chooses to assemble a new type of narrative from the pieces, glimmers and leanings that it gathers, and through it, offers us lessons to think about the knowledges of resistance, non-normativity, and disruption the

Caribbean has always carried. Antiman offers a syllabus in critical queer Indo-Caribbean practice and pedagogy. In it, we find foundational truths about the contemporary intersections of race, sexuality, gender, and diaspora within the queer Indo-Caribbean, importantly turning us to its historical past and our negotiations with its contemporary afterlife.