I was a traveller then upon the moor; . . .

Beside a pool, bare to the eye of heaven

I saw a Man before me unawares:

The oldest man he seemed that ever wore grey hairs. . . .

And him with further words I thus bespake,

“What occupation do you there pursue?

This is a lonesome place for one like you.”

He told, that to these waters he had come

To gather leeches, being old and poor:

Employment hazardous and wearisome!

And he had many hardships to endure:

From pond to pond he roamed, from moor to moor;

Housing, with God’s good help, by choice or chance;

And in this way he gained an honest maintenance.

– William Wordsworth

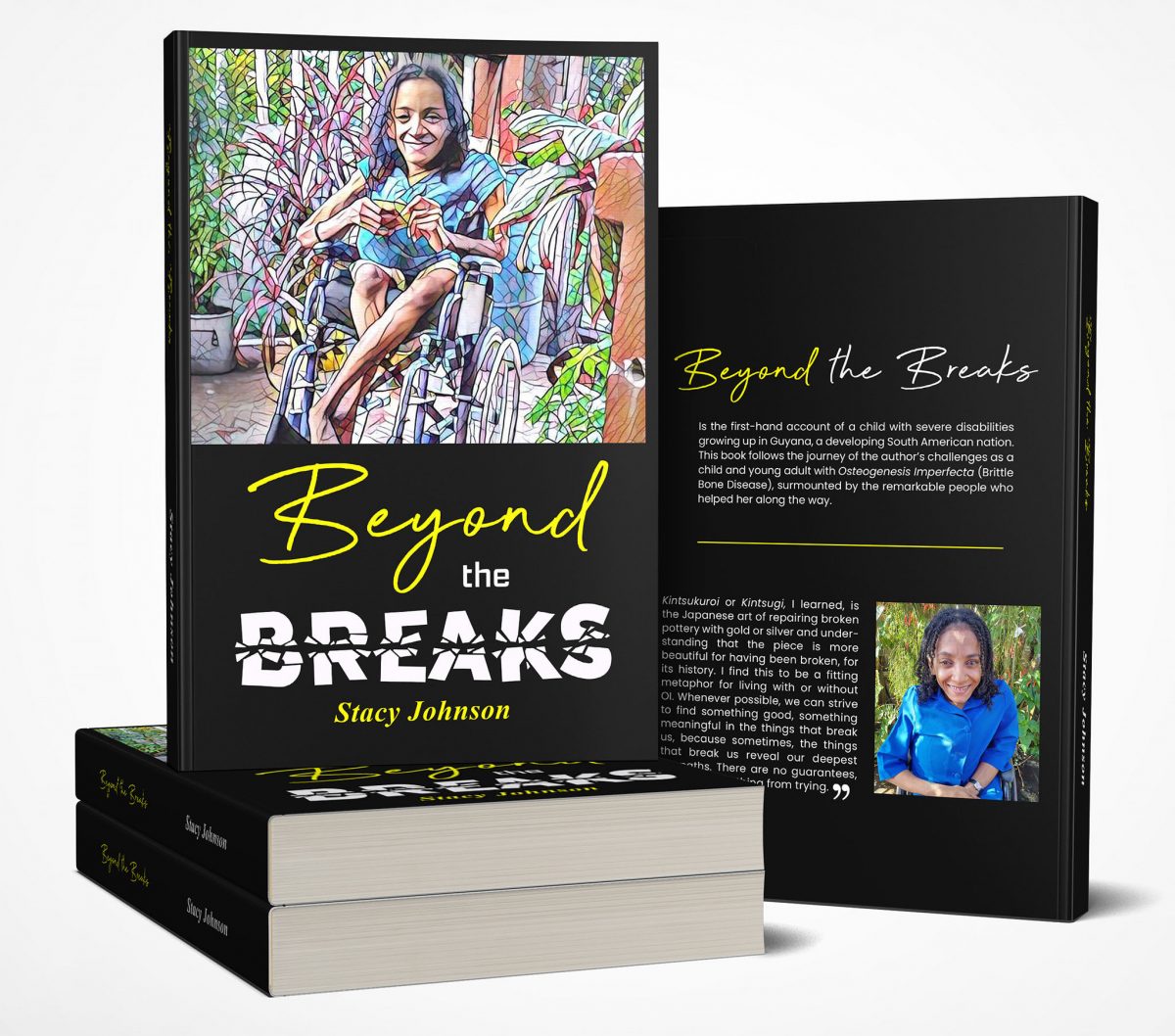

[Stacy Johnson, Beyond the Breaks, Georgetown, Guyenterprise, 2021. 244pp.]

Another new publication has just been released to join the wide and varied corpus of Guyanese literature. Written by Stacy Johnson and published by Guyenterprise, it is titled Beyond the Breaks. My first response to this text takes me back to the poem by the great romantic William Wordsworth called “Resolution and Independence” because it struck me that the poem articulates perfectly, two of the most enduring themes of Johnson’s narrative.

Wordsworth’s poem begins with the natural environment and the way it controls the mood of man, as it often happens with romantic poets. The night was rainy and stormy, but the next day the sun came out brilliantly and “the sky rejoiced in the morning’s birth”. The poet was travelling on the moors and in spite of all the wonders of nature that sang happily about him, his mind was wandering on melancholy and cautionary things like human misery, “solitude, pain of heart, distress and poverty.” Despite the harmony of nature around him, he was unable to find empathy with it. And then he met an old man who reminded him of all the hardships and weariness that plagued his mind.

The man was aged, bent over and weather-beaten, but he was a leech-gatherer who provided for himself by roaming the moors, searching in the ponds and pools of muddy water for leeches, which he then sold to the doctors and the hospitals. Leeches were used in medical practice in the nineteenth century. It was a hard and lonely occupation, but the old man persevered and maintained himself with help from no one. The poet’s mood changed as he was impressed, and prayed that he would be able to attain the resolution and independence exhibited by the leech gatherer.

Resolution and independence are two important themes emerging from Johnson’s Beyond the Breaks. Just as the poet found renewed motivation in the leech gatherer’s perseverance, one may be moved by the determination to be independent reflected in this new book. Yet there are other themes to be discovered.

The publication, launched last week, is an autobiography by a young lady who narrates her life story in the first person, relating details of her birth, her childhood, schooldays, her family – parents, siblings — the world of work, friends, travel and experiences, those who helped and inspired her; about human nature, friendship, aspirations, disappointments and triumphs. When anyone decides to publish a personal testimony of this type, one does so with a very important and serious assumption: that one’s story is worth telling – that it will have something which will interest readers, or more than that, that it will entertain, or inform or improve them in any way. That is a big assumption, if not a presumption, but it is important to a study of this book.

Perhaps the most significant factor of this publication is that it is the autobiography of a girl who was born and grew up with a severe disability known as Osteogenesis Imperfecta (OI), otherwise called Brittle Bone disease, an extremely disruptive condition causing frequent fractures, stunting growth and affecting the physical form. It is rare and largely unknown in Guyana, and Johnson was motivated to tell her story to inform Guyanese and the wider world about this affliction and help them to better understand persons with disability.

Among the aims is to dispel insensitivity, eradicate pity and enlighten the public against stereotyping. Johnson quotes Mark O’Brien, who wrote, “The two mythologies about disabled people break down into – One: we can’t do anything, or – Two: we can do everything. But the truth is, we’re just human.” This new author sets out to speak to her readers about these things.

It is partly for these reasons that I hesitated to review the book. It is clearly well outside of my area of expertise, and I thought that it could better be handed over to my colleague at the University of Guyana, Dr Lydon Lashley, who is an expert in Special Needs Education and could better relate to a dialogue concerning children with disability and children with special needs.

These are issues raised by Johnson deserving of public education, human concerns and intellectual thought. This is even more apposite since the book very strongly resists stereotyping, insensitivity, discrimination, and the limitations suffered by persons with disability because of other people’s lack of knowledge or the absence of facilities and inaccessibility still present in most buildings and institutions in Guyana.

The autobiography contains in excess of 200 pages of narrative introduced by a Foreword from Geraldine Maison Halls, a rehabilitation specialist. As an After-word, the final chapter is a valuable history of the Ptolemy Reid Rehabilitation Centre with high praise for its Head, Hyacinth Massay, publicly known as Cynthia Massay. The centre is a major feature in the book because of its general work among children with disability and its crucial role in Johnson’s life.

The narrative is governed by a good deal of intelligence. The personal stories are fortified by comments about a variety of things, including much of scientific importance and contributions to knowledge about OI and about many aspects of disability. Parti-cularly when it comes to human weaknesses and negative or insensitive attitudes among people generally, Johnson manages to criticise and admonish entirely without preaching or wearisome scolding. These are woven unobtrusively into the narrations.

It is known that Vic Insanally and Guyenterprise were instrumental in the book’s publication, and this must have helped with the finished product. It is neatly packaged, very well edited and the writer is articulate with an effective command of language.

The tale told is much punctuated with sadness and the overall story is one of unwanted suffering, personal struggle and the exceptional, exemplary, care and indefatigable attention of parents Roy and Pamela Johnson, which is nothing short of heroic. Yet, with all the tragedy and painful episodes, it is a remarkably mature narration enhanced by a consistent sense of humour. Very often humour comes to the rescue of what might have been awkward or maudlin.

The description of incidents is detailed, sometimes to a point where readers might feel they did not really have to be provided with that piece of information. But the general trend, which also accounts for such awkward moments, is that Johnson writes with a remarkable degree of frankness and intimacy – a candour born of honesty and considerable courage.

What comes over as well, is how ill equipped the society is to treat and accommodate people with disabilities. Johnson was denied a sixth form education and experience. The University of Guyana did undertake an exercise some years ago aimed at making the campus more accessible to impaired potential students, including new facilities in the library, ramps and lavatories which were remodelled and built. The university did realise the need to bring itself up to that standard. But during those years of effort, the funds were insufficient, and still, today, adaptability is prohibitively expensive.

The one bright development is that the unwanted COVID-19 pandemic restrictions have taught the university to move rapidly into online modes of instruction. It is now possible for a person with disability to access a degree through classes delivered online.

There are several short chapters, and their brevity will help the reader get through passages that might be tedious. What helps to make them easy to read is the generosity of spirit in the writing, which extends to the titles – often witty and consistently metaphorical with a marked sense of irony. They take us through the many themes explored, which include friendship, fidelity, insincerity, hurt, perseverance and triumph.

It is best to summarise the intentions behind the publication of Beyond the Breaks with the writer’s own words.

“Writing this book was first and foremost a love letter to the many people in my life, who have been an important part of my story, knowingly or unknowingly. . . In the moments where I doubted my own story was worth telling, I would remember them. . . . My parents, my siblings, my family and friends, my doctors, my therapists, my teachers and my colleagues. To all of you, thank you.

“At the very least I hope to tell a good story, one that is worth telling.

“My second reason is . . . I wanted to provide an honest look into the life of someone with a disability, especially one growing up against the backdrop of a third world country such as Guyana. . . . It could help to enable pwds [people with disabilities] to receive quality education, employment or to be able to live independently and participate fully in society.”

Johnson wants to encourage other pwds to tell their own stories, and to raise awareness of Osteogenesis Imperfecta in Guyana and the Caribbean. She can be assured that in Beyond the Breaks a good story is told. It is well worth reading and can be recommended to a wide audience.