So, we have come to the end of these reflections on the 150-year-old story of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages, popularly called “sweet drink” in Guyana.

So, we have come to the end of these reflections on the 150-year-old story of nonalcoholic carbonated beverages, popularly called “sweet drink” in Guyana.

This series highlighted a popular product in Guyana’s food and beverage culture. It answers this question: If “sweet drink” could talk, what textured story would it tell? So far, it has been a multi-dimensional story about an innovation in British Guiana during the early post-emancipation years and the consequences of its adoption by society.

It is a story about the Guyanese experience over the past 150 years. It is a story closely connected with working people, and it is closely intertwined with moments of profound change in the making of contemporary Guyanese society. One such was the dramatic growth in the size and diversity of the population which took place between 1838 and 1899, the end of the 19th century.

This is also a story of a product about which most Guyanese, at home and abroad, have shared memories. These are products that “flavor” the sense of being Guyanese. The sweet-drink story increases our understanding of the forces at work in Guianese society during the early post-emancipation years (1838–1899). The consequences of those years continue to influence all relationships in the complicated and complex multi-ethnic Cooperative Republic of Guyana.

I am grateful to the growing number of Guyanese scholars and intellectuals who have been conducting research and writing about this pivotal period in the making of modern Guyana. That body of work is delineating the nature and scope of the forces that were dominant at that moment in the Guyanese experience. It is supporting the textured understanding of the interplay among the ideology of racial superiority, the sugar industry, demographic change, industrialization, food and nutrition, urbanization, culture and aesthetics, among others during this pivotal period in the development of the modern Guyanese nation.

This influential body of work guided the thrust of the series. It directed where to look for sweet drink’s textured story. Some of these works are listed in the references at the end of this installment.

What follows is the highlights of 150 years of sweet drinks in Guyana. Population change, and its place in shaping a set of related beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors which impact human relations in contemporary Guyanese life, is privileged in this take on sweet drink’s textured story.

The 1838–1899 Churn

On August 2, 1838, British Guiana continued to be a colony dominated by finance capitalism, with sugar as the core of the economy. In 1870, the year we associate with the birth of Guyana’s sweet drink industry, only 32 years had passed since the country was a slave society. The society was in churn. The old order retained power. Sugar was the maximum leader. An observer in 1853 (15 years after emancipation) opined that the economy was controlled by “some fifty or sixty gentlemen in Great Britain.” He noted:

“If the capitalists connected with Guiana, were merely to issue orders to suspend the workings of their estates on and after the first of January next, and which they might possibly do without any great loss or inconvenience to themselves, in twelve months more the country would be a wilderness and the people remaining in it reduced to starvation and famine.”

Between 1838 and 1899, British Guiana’s sugar industry faced intense international competition from sugar produced more cheaply through slave labor in Cuba and Brazil. Slavery ended in 1886 in Cuba and in 1888 in Brazil. This sustained tension within the industry led to anxiety among the plantocracy, the colony’s ruling class. There was an increase in sugar estate closures and personal bankruptcies. Many estate managers experienced declines in their lifestyles. The above mentioned observer of British Guiana in 1853 wrote: “He [estate manager] breakfasts, and as the clock strikes twelve, recollects the day when he always drank a sangaree at that hour, but bad times and reduced salaries compel him to quench with lemonade his ever-burning thirst …”

In response to the international competition, sugar producers in British Guiana invested in technology and refined their approaches to produce a product that was popular internationally because of its crystals. Demerara crystals were a sought-after muscovado sugar in Europe and North America. Its production required “continuous labor,” an abusive system.

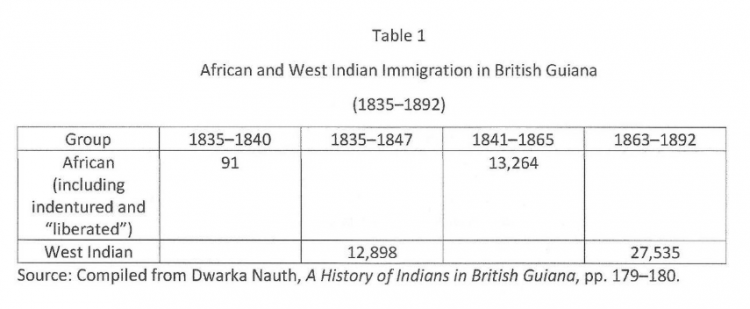

When enslaved Africans were emancipated on August 1, 1838, the colony’s total population of approximately 136,000 included approximately 97,000 formerly enslaved Africans. Demerara, Essequibo, and Berbice were reputed for high death rates among enslaved Africans. In 1817, the enslaved African population was 101, 712. In1832, it was 88,623. More than 13,000 Africans died, the result of over work, pestilential conditions, and inadequate nutrition. In addition, the birth rate among African people in the colony was low. The arrival of 53,788 African indentured laborers, Africans “liberated” from the illegal Cuban and Brazilian slave trade, and West Indian immigrants between 1834 and 1892 halted the decimation of African people during the early post-emancipation years. (Table 1 shows the number of Africans and West Indians who migrated to British Guiana during this period.)

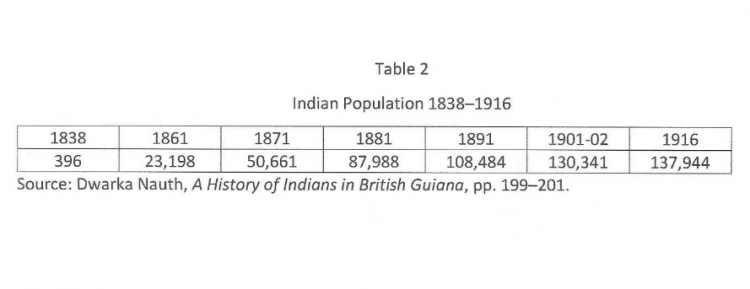

As anticipated, after emancipation, approximately 70 percent of the formerly enslaved Africans left the sugar plantation to establish independent villages. The government responded by funding immigration schemes to bring in labor from Africa, Asia, Europe, and the West Indies, starting with Portugal in 1834. By 1899, India had become the major source for new labor. Table 2 shows the growth of the Indian immigrant population between 1838 (the arrival of the first Indian immigrants) and 1916 (the end of the state-funded Indian immigration program).

These demographic developments had social, cultural, and political consequences. During this period, the colony’s sugar interests required that steps be taken to protect the industry from the potential political power of the newly emancipated African and other subordinated people. In 1842 and 1846, formerly enslaved Africans organized two strikes with varying degrees of effectiveness. These threats to the status quo triggered the use of the state’s coercive power, including oppressive taxation, seizure of the power of village councils, amplification of the anti-African propaganda developed during the slavery era, and the expansion of custodial facilities (Mazaruni [1843] and Onderneeming [1879]). The use of state power to coerce and to punish political opponents has persisted in Guyanese politics.

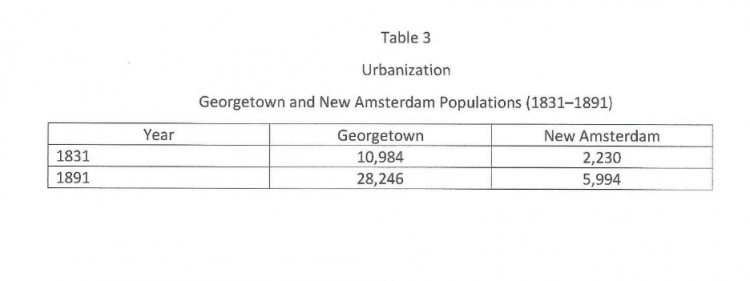

A consequence of the plantocracy’s assault on the recently freed Africans was their increased migration to the colony’s urban centers, Georgetown in Demerara, and New Amsterdam in Berbice. (Table 3 presents the population growth in Georgetown and New Amsterdam during this period.) This led to a new era in African mobilization for self-determination and economic independence.

In Essequibo, the population increased between 1831 and 1891 (29,465 to 43,367). This was the result of immigration from India.

The Indian Presence: 1838–1899

The Indian immigrant community was internally diverse. Most were poor peasants from Northern India. Others were from other parts of India and the British Empire in the Indian subcontinent. A majority were fleeing the consequences of the British Raj, natural disasters, and poverty to seek a better life. For a long time, there were more men than women. Most were Hindu, many were Islamic, and a few may have been Christian.

A crucial consequence of this development was the complication of race relations a colony organized by the ideology of racial superiority. The new complication was relations between African and Indian people. Indian indentured laborers and enslaved Africans encountered 1838. Africans were not emancipated until August 1, 1838, roughly four months after the first Indian arrivals. The brutality of continuous labor as practiced in 1838 resulted in the suspension of the Indian indentureship program between 1839 and 1844. When it was reopened in 1845, there were changes to sugar estate work in British Guiana.

The early encounters between Africans and Indians on the sugar plantation were mediated by propaganda constructed from racist fiction, mythologies, stereotypes, caricatures, and the brutalizing and dehumanizing reality of surviving continuous labor. Robert Moore’s essay “Colonial Images of Blacks and Indians in Nineteenth-Century Guyana” lays bare the scope of this devastating and lasting consequence of the sugar plantation. Its legacy continues to be reflected in contemporary Guyanese society and ethnopolitical practice.

By the end of the 19th century, the Indian immigrant community was internally stratified. There was a small upper class featuring high-caste religious leaders, professionals (doctors and lawyers), and successful entrepreneurs. There was an emerging middle class drawn from jobs (e.g., sirdhars, clerks, and dispensers) on the sugar estates and in the civil service. A majority of Indians were working people engaged in thirst-generating labor on the sugar estates and in urban environments in hot and humid British Guiana. By the end of the 19th century, the community of Indian immigrants had developed key institutions and were already active in imagining a future for themselves and the colony. In 1950, Dr. Cheddi Jagan, the son of indentured Indian immigrants, along with the descendants of former enslaved Africans and former indentured workers, formed the colony’s first mass political party, the People’s Progressive Party, and promoted a vision of an independent and sovereign Guyana.

The growth of urban and rural working-class populations engaged in thirst-generating activities spurred investments in the sweet drink industry. Thus, by the first decade of the 20th century, at least 14 bottlers were located near communities dominated by working people, an attractive mass market. Working people became the major consumers of sweet drinks.

The Indian indentureship program ended in 1916, and most of the term-expired Indian immigrants exercised the option to stay in British Guiana. The sweet-drink story reveals the investments of Indians, especially Muslims in the industry. This includes the establishment of bottling facilities in rural villages and urban working-class communities.

During the 1920s, there was an increase in social activities, such as thirst-creating and social drinking events (e.g., balls, dances, and excursions). Ethnic groups opened social and recreational clubs (Negro Progress Convention, 1920; Chinese Association, 1920; BGEIA, 1924, Portuguese Club, 1924; and St. Andrew’s Association [representing Scots], 1928). The embryonic sweet drink industry serviced this and the primary working-class market segments. Despite the persistent economic depression, the 1930s saw increases in major public activities to commemorate the empire and to build morale in British Guiana. Sweet drink was part of that action. The end of the 1930s ushered in World War II (1939–1945) and the expansion of the major U.S. cola brands (Coca-Cola and Pepsi-Cola) and their associated practices and messages in the colony.

By the end of 1945, the world was engulfed in another war, the Cold War: “a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies.” In 1953, British Guiana was an early flash point in this war. Peter D’Aguiar, the managing director of DIH, was a vocal anti-Communist. His actions might have cost his company business in the colony’s East Indian communities. According to a confidential source, East Indians boycotted his brands because his actions were seen as being against the native son, Dr. Cheddi Jagan. Research on the folk songs of Indians in rural British Guiana during the early 1960, identified songs disparaging Peter D’Aguiar and recommending voting for Dr. Jagan.

By 1966, Guyana had become an independent state with Forbes Burnham as the prime minister and Peter D’Aguiar as the minister of finance. From the 1970s, Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham was de jure and de facto, the nation’s maximum leader. According to relatives, he was not a “sweet drink” imbiber. His preference was for “homemade drinks.” His death in 1985 marked the beginning of a shift in political ideology and economic practice. When the PPP returned to power after winning the 1992 election, it inherited a changing economy. Formerly state-owned properties, such as Demerara Distillers Ltd. (DDL), had been privatized. DDL’s entry was a key factor in the reenergization of the sweet-drink industry. The changed political–economic landscape demonstrated that the economy was open to international investment and would offer the necessary protections. This encouraged the entry of SM Jaleel and Rudisa into the Guyanese sweet drink market.

Since the 1990s, the Guyana sweet drink industry has shown consistent growth. The annual reports from Banks DIH and DDL show increasing after-tax profits and sustained payments of dividends to shareholders.

The sweet-drink industry is part of Guyana’s social fabric. It is a sensitive barometer of Guyanese life. The companies modernized business practices in Guyana. They have evolved from single-product entities to conglomerates that own banks, insurance companies, restaurants, bakeries, shipping lines, and specialized packing plants. In addition to demonstrating integration, and synergy, these companies have been associated with innovative advertising and marketing techniques. They have influenced the aesthetics of the advertising industry through historic marketing, publicity, and marketing campaigns.

The advertising campaigns developed by the local advertising community for the sweet drink industry played a significant role in the development of the post-independence Guyanese identity, which includes a sense of self-efficacy. Freed from the norms and aesthetics of the colonial era, these campaigns (via newspapers, billboards, radio jingles, and cinema slides) presented images (e.g., landscapes, seascapes, buildings, community activities) of the Guyanese experience. This contributed to the mood of self-confidence evident in the society during the early post-independence years.

The leading sweet-drink producers have been characterized as having responsible and forward-looking labor relations practices. Banks DIH and DDL are unionized. Worker participation in management, first promoted as a national industrial relations practice in the public sector, is alive in the sweet drink industry. The workers’ conditions and benefits exceed the national norms.

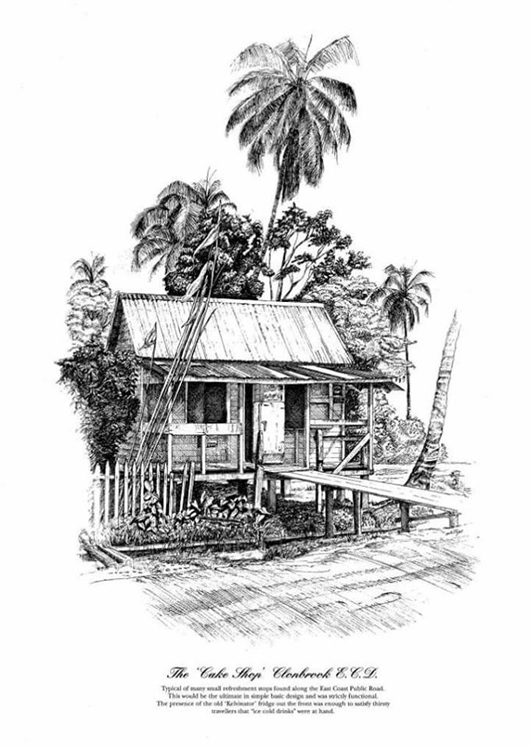

The sweet-drink industry has also made an imprint on Guyana’s industrial and commercial architecture. Examples are Caesar Castellani’s bar in Demico House, Wieting and Richter’s Cold Storage and Ice Factory, the art deco design of the old DIH bottling plant opposite Parliament buildings, the traditional cake shops, the modern supermarkets, and the Banks DIH rotunda at Thirst Park.

POSSIBLE FUTURES

The future of Guyana’s sweet drink industry will be influenced by franchising, the ongoing dependence of imported inputs, the soft drink industry in the United States, and public health and environmental issues. Of immediate importance is the industry’s response to public health challenges.

Public Health Concerns

Guyana is part of the region with the highest sweet-drink consumption in the world. According to the results of a global study published in 2015, the Caribbean region drinks more than “twice the amount of an individual does elsewhere.” A recent calculation suggested that Guyanese consumed 1.4 liters (2.959 pints) of sweet drinks per day. This corresponds to an average daily intake of almost 80 teaspoons or 333 grams of sugar: 15 times the daily recommended daily sugar intake. Guyana’s per capita consumption is 135 gallons (511 liters) per year according to 2020 data from Guyana’s Bureau of Statistics. U.S. Centers for Disease Control reports have attributed more than 44 percent of deaths in Guyana to excessive sugar consumption.

Among the responses by the large global brands to consumers’ greater health consciousness, especially concerns about excessive sugar, have been the use of artificial sweeteners, the introduction of diet colas, and the diversification of their nonalcoholic beverage lines. For example, Coca-Cola and Pepsi also produce fruit juices, bottled water, sports drinks, and energy drinks. This diversity was evident in Guyana in June 2021. Nelsonia Budhram-Persaud, a social scientist at the Center for Communication Studies at the University of Guyana, recently commented on risky behaviors associated with energy drink consumption in Guyana.

Energy Drinks: High sugar and caffeine. Consumers, costs, the poor. These are low-cost, ranging from US$1 to US$3 (Red Bull). There is significant “Red Bull advertising.” In July 2021, the popular brands were XL and Turbo. These are cheaper options to Red Bull. The primary consumers are MALE, students, manual laborers, and night-shift workers. It is sometimes, many times, used in lieu of a MEAL. ABUSE: Energy drinks are used as a mixer with alcohol. There have been deaths from this practice.

Ethics

Another international concern is the cultivation of replacement consumers. In the United States, efforts are afoot to increase consumption among children, African Americans, Hispanics, and other traditionally marginalized populations. A 2017 Healthy Caribbean Coalition study indicated that more than 70 percent of Guyanese school children aged 13 to 15 reported drinking one or more carbonated soft drinks during the previous 30 days. This was identified as a serious risk factor for childhood obesity. In recent years, several Caribbean states, including Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago, have restricted the sale of sugary beverages at or near schools. Guyana does not appear to have adopted such a measure. Maybe this could be a task of the recently reconstituted Presidential Commission on Non-Communicable Diseases.

Research and Development

I am not privy to any intra-industry conversations about the future. I would suggest that the industry must address the issue of dependency on internationally sourced inputs, including flavoring, essences, and white sugar. It appears that all sweet drinks in Guyana are based on imported artificial or synthetic flavors. In recent years, Guyana’s agro-processing community has made some admirable strides in bringing new, well-packaged products to the domestic and international markets. The Guyana School of Agriculture and the University of Guyana’s Institute of Applied Science and Technology have been leading actors in this development. Will collaborations between these institutions and the sweet drink industry increase the domestic capacity to produce shelf-stable Guyanese fruit-based flavorings?

The preliminary story of sweet drinks in Guyana is impressive. Along the way in this series, we met a community of influential men who made their mark. It also offered glimpses of a few women, such as Gertrude Gibson, Norma Gobin, June Ramsammy, Sharon Sue Hang Baksh, and Kavorn Kyte-Williams.

Women were among the owners of the early bottling plants. Gertrude Gibson, a widow, owned and operated the Verdun Aerated Soda Factory before selling it to Alfred Mohamed. Norma Gobin was part of the Excelsior Aerated Water factory in New Amsterdam. June Ramsammy was the first human resources manager at Banks DIH. Sharon Sue Hang Baksh is currently DDL’s director of technical services, and Kavorn Kyte-Williams is Banks DIH’s company secretary and legal officer. The story of women in Guyana’s industrial development deserves a full account.

International Relations

Guyana’s sweet-drink industry has been part of Guyana’s international trading scene for as long as it has existed. The sweet-drink industry has remained engaged with the international community to obtain raw materials. In recent years, it has actively targeted the diaspora markets. In an interesting twist, Guyana Pride lemonade (bottled in Canada by Bedessee Imports) and Tom Boy (bottled in New York by Alfred Mohamed’s grandson) are now exported to Guyana.

A new generation of carbonation and bottling technologies is becoming available, partially in response to the craft beer, boutique soda, and nonalcoholic drink preferences of millennials and Generation Z in Europe and the United States. Feedback to this series suggests an interest in authentic local flavors, such as soursop, golden apple, and tamarind.

Given the aging population and diabetes prevalence, which invariably require special diets, another product line could be liquid foods. The Guyanese marketplace is already replete with a new generation of “healthy” liquid food drinks (aloe vera and other smoothies). Concerns about deceptive advertising have been expressed.

Is it possible that hot and humid Guyana is poised for a new, potentially healthier, sweet drink to quench our persistent thirst? Could there be an opportunity for a new generation of entrepreneurs, especially women, to try their luck?

Acknowledgment

Thank you for participating in the serialization of Sweet Drink: A Preliminary Exploration of the Social History of Nonalcoholic Carbonated Beverages in Guyana (1870–2020). Your comments, corrections, and leads have been important and truly appreciated. They will guide the next phase of this project: publication as a book that will include additional photographs and illustrations, an index, and a bibliography.

Thank you, Andre Haynes, Editor, Sunday Stabroek, for this partnership.

Selected Resources

Bahadur, G. Coolie Woman: The Odyssey of Indenture. Chicago: The University Press of Chicago, 2014.

Bernard, D. “Folk Traditions and National Development: A Role for African Folk Music from Guyana.” A paper presented to Soundscapes: Reflections on Caribbean Oral and Aural Traditions Conference, The University of the West Indies, Barbados, June 2005.

Braithwaite, C. “The African-Guyanese Demographic Transition: An Analysis of Growth Trends, 1938–1988” in Themes in African-Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998, pp. 201–234.

Cambridge, V. Musical Life in Guyana: History and Politics of Controlling Creativity. JACKSON: University Press of Mississippi, 2015.

Candlin. K. The Last Caribbean Frontier, 1795–1815. United Kingdom: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012.

De Barros, J. Order and Place in a Colonial City: Patterns of Struggle and Resistance in Georgetown, British Guiana, 1889 – 1924. Montreal: McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2002.

Ferguson, T. To Survive Sensibly or Court Heroic Death: Management of Guyana’s Political Economy 1965–1985. Georgetown, Guyana: Public Affairs Consulting Enterprise, 1999.

Gafoor, A. The Evolution of Writing in English by and about East Indians of Guyana 1838–2018. Hertford, HANSIB, 2018.

Hunter, W. A Creole Family: An Unfinished Memoir. Unpublished manuscript in the author’s collection. 2005.

Landowner [John Brummell]. British Guiana. Demerara after 15 years of Freedom. London: T. Bosworth (215, Regent Street), 1853.

McGowan, W. A Survey of Guyanese History. Georgetown, Guyana: Guyenterprise, 2018.

McGowan, W, James Rose, David Granger. Eds. Themes in African-Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998.

Moore, B. “The Social and Economic Subordination of Guyanese Creoles after Emancipation” in Themes in African-Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998, pp. 141–157.

————. African-Guyanese Political Disempowerment during the 19th century” in Themes in African-Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998, pp. 235–249.

Moore, R. “Colonial Images of Blacks and Indians in Nineteenth-Century Guyana.” In Bridget Brerton and Kevin A. Yelvington (eds). The Colonial Caribbean in Transition: Essays on Postemancipation Social and Cultural History. Jamaica: Press of the University of the West Indies, 1999, pp. 126–158.

Nauth, D. A History of Indians in British Guiana. London: Thomas Nelson and Sons, Ltd., 1950.

Nehusi, K. A People’s Political History of Guyana 1834–1964. Hertford: Hansib, 2018.

A.W. Perot & Co., Claimants. A Review of the Case of the United States vs 712 Bags of Dark Demerara Centrifugal Sugars. Tried at the September Term of the District Court of the U.S. for the District of Maryland. Baltimore: Lucas Brothers, 1878.

Rodney, W. A History of the Guyanese Working People, 1881–1905. London: Heinemann, 1981.

Rogers, E. Diffusion on Innovations. 3rd edition. New York: The Free Press, 1983.

Rose, J. “The Strikes of 1842 and 1848” in Themes in African-Guyanese History. Georgetown: Free Press, 1998, pp. 158–200.

Ruhomon, P. Centenary History of East Indians in British Guiana (1838 –1938). Georgetown: The Daily Chronicle, n.d., ca. 1946.

Seecharan, C. India and the Shaping of the Indo-Guyanese Imagination 1890s–1920s. Leeds: University of Warwick and The Peepal Press, 1993.

—————–. Bechu: ‘Bound Coolie’ Radical in British Guiana 1894–1901. Kingston, Jamaica: The University of the West Indies Press, 1999.

Stoll, A. “Between a little rock and hard place.” A paper presented to symposium to commemorate the 50th anniversary of Guyana’s independence, National Conference Center, Turkeyen, Georgetown, 2016.