(BBC) There are two murals of black footballers facing one another across an alleyway in Glasgow. One helped shape football as we know it, the other is Pele.

Andrew Watson captained Scotland to a 6-1 win over England on his debut in 1881. He was a pioneer, the world’s first black international, but for more than a century the significance of his achievements went unrecognised.

Research conducted over the past three decades has left us with some biographical details: a man descended of slaves and of those who enslaved them, born in Guyana, raised to become an English gentleman and famed as one of Scottish football’s first icons.

And yet today, 100 years on from his death aged 64, Watson remains something of an enigma, the picture built around him a fractured one.

His grainy, faded, sepia image evokes many different emotions: awe, pride, passion, and for one man in particular, discomfort.

When Watson moved to Glasgow in 1875, aged 18, he had hardly played football.

It was a time before professionalism, when the sport was still evolving and a single set of rules was yet to be universally adopted.

Within six years he’d established himself as one of the most talented and well-respected players, a trailblazer who helped popularise the Scottish ‘passing and running’ game – an early step in football’s evolution towards what we recognise today.

Watson twice played against England, and on each occasion Scotland were convincing winners. The second victory, 5-1 at the original Hampden Park, was a pivotal result that convinced the English Football Association its approach needed to change.

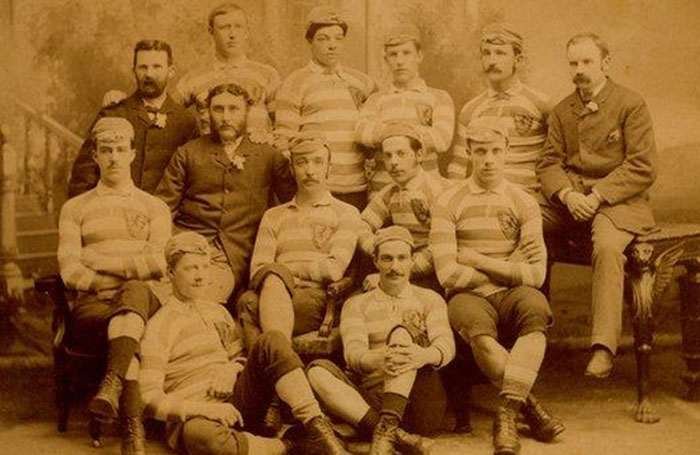

They turned to Watson to show them the way as a new elite amateur team was formed; Corinthian FC would later be credited with popularising football around the world. Watson, a public school educated player who would have spoken with the upper class accent of his new team-mates, was among the first recruits.

He assumed the role of ‘Scotch Professor’ and taught his English peers – both at Corinthian and numerous other clubs and representative sides – “the science” of a more dynamic passing style.

He is seen as a conduit who helped modernise football during a period of great upheaval that signalled the “death” of the “individual, dribbling game” – characterised by a single player running with the ball at his feet surrounded by eight forwards – that had been favoured by the English.

“Pele was a genius footballer, but there are thousands of genius footballers whose influence dies with them the second they retire,” says Ged O’Brien, founder of the Scottish Football Museum.

“You can look at any game of football being played anywhere in the world – by any person of any gender or ethnicity or culture – and the ghost of Andrew Watson will be looking down on you, because they are playing his game.

“Watson is the most influential black footballer of all time. There is nobody that comes close.”

During his lifetime, Watson’s influence was felt across the game. He was a captain, a national cup winner, an administrator, investor and match official, each achievement and contribution made as the first black man to do so. Historians, researchers and academics have worked hard to bring his legacy to light. But unravelling his personal story has presented a different challenge.

Watson was born in 1856, in Georgetown, Demerara, a colonial trading post established by the Dutch, captured by the French, then re-named by British rulers who imported slaves from Africa to work on its plantations. Now it’s the capital of Guyana – which has been a republic since 1970, four years after it declared independence from Britain. It borders Suriname, Venezuela and Brazil.

Watson moved to Britain aged around two. He was educated at some of the finest schools in England. His family boasted significant wealth and powerful family connections.

Liverpudlian poet Mark Al Nasir spent years researching Watson’s background. After first “seeing himself” in images of a 19th-century footballer broadcast on a BBC TV documentary in 2002, he traced his own ancestry back to Watson’s in Guyana.

“I saw a black guy from Guyana who was the world’s first black footballer, who looked like me and has our family name. I thought: ‘We have to be related,’” says Al Nasir, who changed his name from Mark Watson when he converted to Islam.

“I grew up to feel worthless, that I was nobody, that I was from nothing. There was nothing to give me pride or dignity in being black. So seeing someone like him, one of the very architects of the game, I needed to find out what our connection might be.

“I was looking for a sense of black pride, something in my history to be proud of.”

What Al Nasir found were ancestors who were both slaves and slave traders.

“The blood of both courses through my veins and that is a dilemma that I have to reconcile within my own soul,” he says.

“And Andrew Watson’s family consisted of both.”

Watson’s mother, Anna Rose, was a black woman born into slavery and freed as a young girl, along with her mother Minkie.

His father, Peter Miller Watson, was a white Scottish solicitor among the most influential figures in Demerara. He looked after the affairs of Sandbach, Tinne and Co – a firm that exported sugar, coffee and rum and had been involved in the slave trade.

In a complex family tree is also John Gladstone, one of the largest slave owners in the West Indies and the father of William Gladstone, who served for 12 years as British Prime Minister over four terms between 1868 and 1894.

Watson’s family in the 19th Century were also expanding into banking and railway development – amassing huge wealth in the process.

“Andrew Watson was born into one of the most powerful, dynastical slavery conglomerates in the history of the British slave trade,” Al Nasir says.

“This is a guy who lived the life of privilege. He had a Prime Minister for a cousin and his family owned a bank.”

After moving to England with his elder sister Annetta, Watson attended Heath Grammar School in Halifax, West Yorkshire, and went on to study at King’s College, London, as well as Glasgow University.

Aged 21, he drew on an inheritance of £6,000, plus interest, left to him following his father’s death. The sum would be worth around £700,000 today. He invested some of the money in his football club, Parkgrove, as well as in a wholesale warehouse business.

After moving on to Queen’s Park, where he won three Scottish Cups, The Scottish Athletic Journal profiled Watson in 1885 under the headline: ‘Modern Athletic Celebrities’.

Like many such articles about him, he is described as “first-class” and is said to “play a sterling honest game”. But unlike other reports of the time, there is reference to abuse he had to contend with:

“Although on more than one occasion subjected to vulgar insults by splenetic, ill-tempered players, he uniformly preserved that gentlemanly demeanour which has endeared him to opponents as well as his club companions.”

To those who have researched Watson, it gives a telling insight into what he had to deal with as a black player. No reports of the time explicitly mentioned racism.

“Why has the writer written it?” asks Richard McBrearty, curator at the Scottish Football Museum.

“I’ve read hundreds of these articles and they don’t talk of ‘splenetic, ill-tempered players’ for the white footballers. It’s the only reference I’ve ever seen and it happens to be a line mentioned in an article about a black player. That was part of what he faced.

“It sets him out as a champion of football, not just for his playing prowess but as a black man playing what was basically a white game at that time. He was a pioneer.”

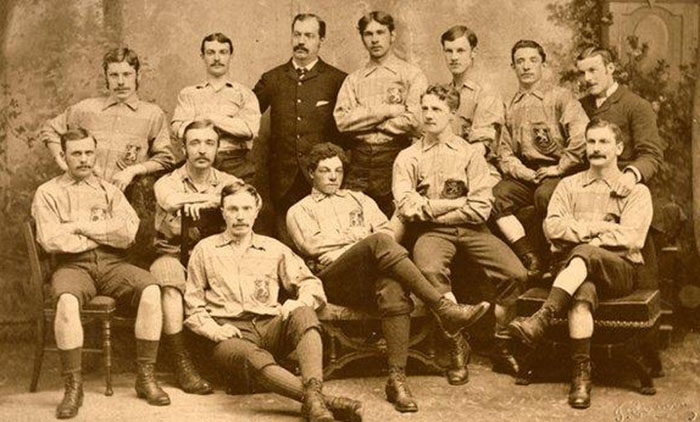

Watson sits front and centre in one of the Scotland national team’s most famous early photos, and his wider influence is now plain to see. So why was he forgotten?

Shortly after arriving in London as a footballer in 1882, Watson’s first wife Jessie Nimmo Armour died. Their two children would remain with their grandparents in Glasgow for the next 30 years. It heralded an unsettled period in Watson’s life where he led an almost nomadic existence playing for numerous teams.

By 1888 he was in the twilight of his career and playing for Bootle – Everton’s main rival on Merseyside at the time. There, he set up a new home with his second wife Eliza Kate Tyler, with whom he had two more children, retired from football and trained as a maritime engineer.

He went to sea, working for the West Indian and Pacific Steamship Company and rising to the rank of chief engineer. To football he was lost. A mention in the Glasgow Evening Post in 1889 referenced that he was “doing well as an engineer”, but from public consciousness his presence faded.

His death was announced in 1921 in The Richmond and Twickenham Times, which referenced him as being cousin to former Prime Minister Gladstone. There was no obituary, no football tributes.

“If you remove Andrew Watson from the timeline of football – and not just wipe him from the history books as previously done – what would have happened to the game?” asks Llew Walker, author of Andrew Watson, A straggling Life.

He adds: “There is a whitewashing of football history as an English game over the past 100 years, and when the Scottish influence is pushed out of the game you also push Andrew Watson’s story out.”

There is a campaign for Watson to be honoured with a statue at Hampden Park. But Al Nasir is against such efforts – because of the footballer’s family ties and the money he was bequeathed later in life.

“If you are going to stand up and say ‘remove William Gladstone’s name from a building at Liverpool University because he received money from his father and his link to the slave trade’, then what argument have you got for putting a statue of Watson up?” Al Nasir asks.

“You can’t apply a different standard to Watson.”

Historian Andy Mitchell believes Watson’s story is “still to be concluded”. Many biographical details remain shrouded in mystery, even if Mitchell himself helped with a recent major rediscovery.

For decades, Watson’s last resting place was unknown. It was thought possibly to be in Australia, possibly Mumbai. Mitchell was the man who found the actual grave, in Richmond Cemetery, in south-west London.

“In some respects, Watson is finally being recognised as a hugely important figure,” says Mitchell.

“And yet there is still so many questions about his life and what he felt. He is an enigma – a very important enigma.”