The opening scene of “No Time to Die” has stayed in mind longer than I expected it to. And the more I try to understand why, the more the moment feels emblematic of how this final entry in Daniel Craig’s James Bond saga works as a film. We first meet a mother and daughter in a wintry getaway. The mother is maudlin and drunk; the girl is alert and precious. The domestic space is interrupted by an assassin, seeking revenge on the absent patriarch. The mother is killed, the daughter escapes. She’s almost successful in outwitting her masked foe, except nature becomes a foe more than a friend and the sequence ends in a moment of unexpected providence that will have implications for the rest of the film.

We’re not quite sure who all the people are in this opening sequence, or why they should matter, although we can guess. But even as the suggestions of import are there, the moment works removed from any sense of character-based value or plot related significance. Linus Sandgren frames the world like a dreamscape that’s just on the verge of becoming a nightmare. Whiteness is unnerving more than comfort, and nature is a latently dangerous force. Our emotional reaction is purely predicated on the filmmaking. For someone generally ambivalent about James Bond in theory, it immediately caught me. But “No Time to Die” is not just an action movie dependent on wonderful aesthetics. It is a James Bond movie, and a James Bond movie with a specific focus on the meditative rather than the propulsive.

Things pick up a few decades later, still pre-credits, and we’re on a languorous European adventure with a retired bond and Madeline Swann (Léa Seydoux) catching up immediately after the events of “Spectre”. We spend what feels like a long stretch watching them dance around each other, and it looks beautiful but it immediately presents a reflectiveness that becomes a liability. Bond and Madeline’s relationship becomes a central bedrock for “No Time to Die”, a dynamic that is consistently affected by the poor chemistry between the two. Their disparate approaches to performance feel even more out-of-sync here. They’re in different genres, not even just different films and so the action sequences when they finally come, they feel not just energetic but merciless. Yes, more of that and not this hand-wringing about emotion.

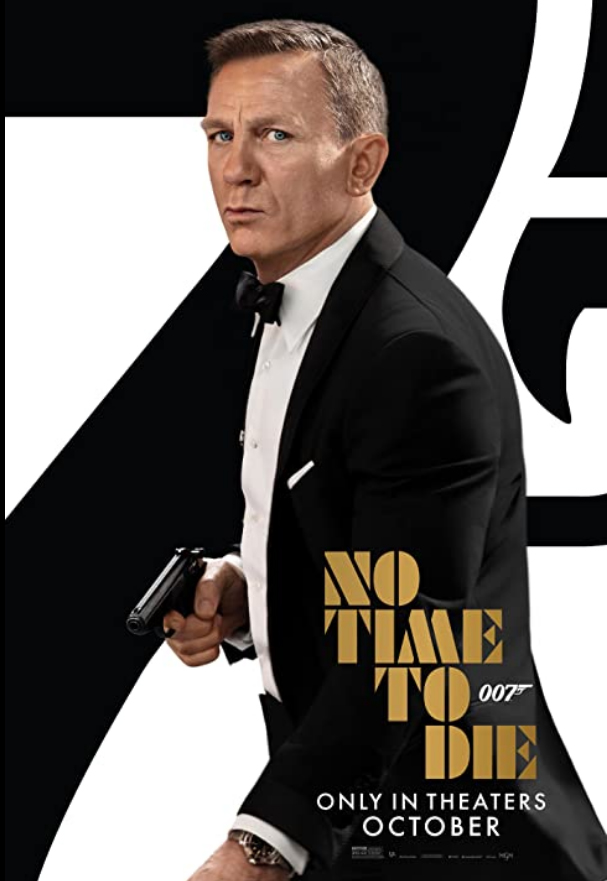

But what do we want in a James Bond? The character, for all the controversy that comes with it, is a cipher at best. The varied actors that have inhabited the character is proof that there’s no one type of James Bond. But, rather, the series can withstand any kind of performer once it builds the film up around it. I’ve been mostly ambivalent about the films built around Craig’s Bond, and some of that is because of my own ambivalence about Craig as a performer. He’s dutifully stoic and committed, but “No Time to Die” works best when it lets him be a beacon of stoicism for other characters to bounce their exasperation off. A quietly humorous reunion of workmates in an apartment. A misjudged attempt at seduction that’s really a shakedown. “No Time to Die” is incredibly effective when it’s working its charms and resisting reflectiveness. No sequence gets this better than a mid-film moment with Ana De Armas in a brief (but excellent turn) that bakes the plot developments into moments of humour and action that work less because of characterisation and more because of an energetic and kinetic devotion to movement.

But at every turn, the script (written by Neal Purvis, Robert Wade, Cary Joji Fukunaga and Phoebe Waller-Bridge) feels like it needs to return to the psyche of James Bond to hit home the VERY IMPORTANT EMOTIONAL THEMES here. Maybe that’s what some want from a James Bond. The psychic depths of “Skyfall” worked for many. But “No Times to Die” feels like proof that that kind of heavy lifting isn’t essential for this series. It’s most evidence in the last 25 minutes where that kind of emotion takes centre stage and everything feels too sluggishly maudlin to be truly engaging.

And it’s curious because even amid the most aggressively sombre moments, you can tell the film gets the need for lightness and litheness. There’s a peripheral moment where Rami Malek’s underutilised villain heaves a sigh in reaction to a trenchant child that feels so specific and careful without being overemphasised. And it’s likely that “No Time to Die,” bearing the weight of being Craig’s last entry and the 25th Bond film, is struggling to meet the inherent expectations. Each specific section is handled with care, but the film feels too oppressive in moment that keeps them from breathing. You can see the accidental muchness in the way that Malek feels like he’s giving a really sharp performance with a lot of thought put into his movement, the cadence of his voice and even the tiresome makeup that insists on facial disfigurement as the way to announce Bond villains. But the film itself can’t find space for him, there’s so much going on.

And, as is the nature of things with so much going on, your mileage may vary on what you find compelling. In this iteration the nanobot arc of the villain, dependent on a slew of science-fiction hijinks, feels like an interruption of the expert action set-pieces. Surprisingly, even with the sour notes of those closing moments, there’s so many more engaging things beyond Bond that I find myself feeling quite pleasant about the entire experience. Where does Bond go from there? Who knows? Really, though, I left “No Time to Die” wanting to see a Cary Joji Fukunaga action thriller without the trappings of Important Bond Issues. In the best moments, he directs this entry with a lightness of touch and insouciance that’s charmingly engaging.

“No Time to Die” is currently playing in local cinemas.