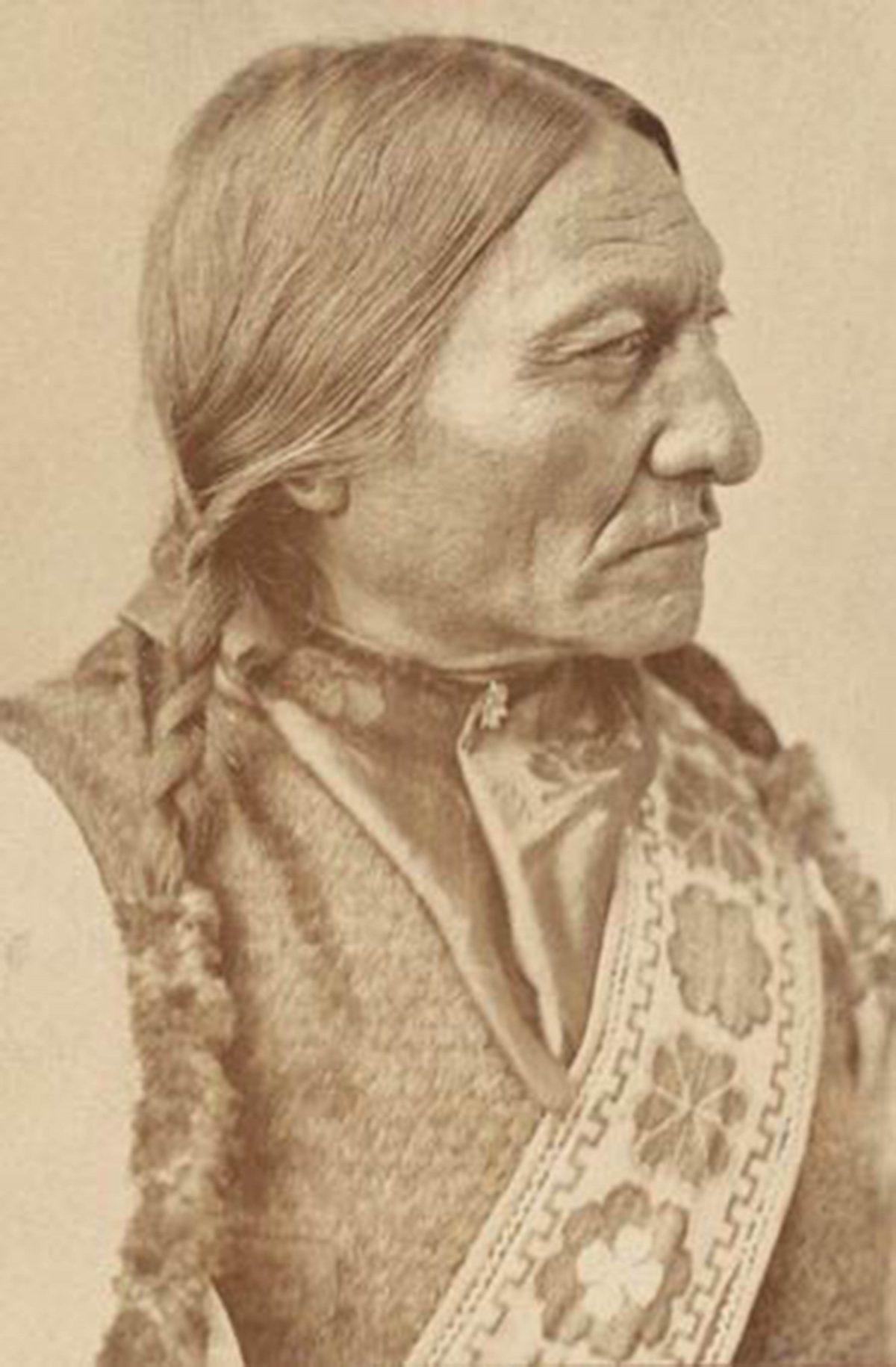

WASHINGTON, (Reuters) – A sample of Sitting Bull’s hair has helped scientists confirm that a South Dakota man is the famed 19th century Native American leader’s great-grandson using a new method to analyze family lineages with DNA fragments from long-dead people.

Researchers said on Wednesday that DNA extracted from the hair, which had been stored at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, confirmed the familial relationship between Sitting Bull, who died in 1890, and Ernie LaPointe, 73, of Lead, South Dakota.

“I feel this DNA research is another way of identifying my lineal relationship to my great-grandfather,” said LaPointe, who has three sisters. “People have been questioning our relationship to our ancestor as long as I can remember. These people are just a pain in the place you sit – and will probably doubt these findings, also.”

The study represented the first time that DNA from a long-dead person was used to demonstrate a familial relationship between a living individual and a historical figure – and offers the potential for doing so with others whose DNA can be extracted from remains such as hair, teeth or bones.

The new method was developed by scientists led by Eske Willerslev, director of the Lundbeck Foundation GeoGenetics Centre at the University of Cambridge.

The researchers took 14 years to discover a way of extracting useable DNA from the hair, which was degraded after being stored at room temperature before being handed over by the Smithsonian to LaPointe and his sisters in 2007.

Willerslev said he read in a magazine about the Smithsonian turning over the lock of hair from Sitting Bull’s scalp and reached out to LaPointe.

“LaPointe asked me to extract DNA from it and compare it to his DNA to establish relationship,” said Willerslev, senior author of the research published in the Science Advances. “I got very little hair and there was very limited DNA in it. It took us a long time developing a method that, based on limited ancient DNA, can by compared to that of living people across multiple generations.”

The novel technique centered on what is known as autosomal DNA in the genetic fragments extracted from the hair. Traditional analysis involves specific DNA in the Y chromosome passed down the male line or specific DNA in the mitochondria – powerhouses of a cell – passed down from mothers to children. Autosomal DNA instead is not gender specific.

“There existed methods, but they demanded for substantial amounts of DNA or did only allow to go to the level of grandchildren,” Willerslev said. “With our new method, it is possible to establish deeper-time family relationships using tiny amounts of DNA.”

Sitting Bull, whose Lakota name was Tatanka-Iyotanka, helped bring together the Sioux tribes of the Great Plains against white settlers taking tribal land and U.S. military forces trying to expel Native Americans from their territory. He led Native American warriors who wiped out federal troops led by George Custer at the 1876 Battle of the Little Bighorn in what is now the U.S. state of Montana.

Two official burial sites exist for Sitting Bull, one at Fort Yates, North Dakota and the other at Mobridge, South Dakota. LaPointe said he does not believe the Fort Yates site contains any of his great-grandfather’s remains.

“I feel the DNA results can identify the remains buried at the Mobridge, South Dakota site as my ancestor,” LaPointe said, raising the possibility of moving the Mobridge remains to another location in the future.