Developing countries, including those in Latin America and the Caribbean, will have to face a worse than originally anticipated, longer-term COVID-19 impact on employment, according to adjusted figures recently released by the International Labour Organization (ILO).

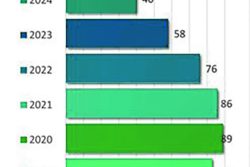

Contrary to the ILO’s earlier projection that global hours worked this year would be 3.5 per cent below pre-pandemic levels, the equivalent of 100 million full-time jobs, the UN agency is now projecting that the global hours worked this year will be 4.3 per cent below pandemic levels, the equivalent of 125 million jobs.

Further, the ILO says that poor countries will have to bear the brunt of the overall percentage of working hours lost on account of the fact that richer countries benefitted from a more timely and efficient rollout of COVID-19 vaccines. The report adds, however, that a likely “two-speed recovery” between developed and developing nations will impact the global economy as a whole.

The current edition of the ILO Monitor also warns that in the absence of “concrete financial and technical support” there is likely to occur a “great divergence” in employment recovery trends between developed and developing countries.

It discloses that in the course of the third quarter of 2021, the total number of hours worked in high-income countries were 3.6 percent lower than the fourth quarter of 2020. By contrast, the gap in low-income countries stood at 5.7 percent and in lower-middle income countries, at 7.3 percent.

According to the report Africa, the Americas and Arab states showed declines of 5.6, 5.4 and 6.5 percent respectively, the largest across countries, globally.

What the ILO regards as the great divergence in the loss of work hours between rich and poor countries was driven by what it says have been major differences in the roll out of vaccinations and fiscal stimulus packages. It estimates that for every 14 people fully vaccinated in the second quarter of 2021, one full-time equivalent job was added to the global labour market. In effect, the uneven rollout of vaccinations meant that the positive effect was largest in high-income countries, negligible in lower-middle-income countries and almost zero in low-income countries. The UN agency says, however, that these imbalances can be rapidly and effectively addressed through greater global solidarity in respect of vaccines. Its estimates assert that if low-income countries had more equitable access to vaccines, working-hour recovery would catch up with richer economies in just over one quarter.

What has also undermined the rate of recovery in poor countries, the ILO report says, is the fact that the gap in the disbursement of fiscal packages remains largely unaddressed. Around 86 percent of global stimulus measures were concentrated in high-income countries, according to the report.