Early in “The Power of the Dog”, a character tearfully confesses to another, “I just wanted to say how nice it is not to be alone.” The line is a trick. Or, more accurately, the clarity of its meaning is marred by the incongruity of the moment. The line, on its own, feels like a romantic entreaty. Except although the characters are lovers, they are not in anything resembling an embrace at the time. In fact, their relationship so far despite overtures of closeness, feels awkward. An awkward ghost of a dance precedes the confession. Their embrace, which happens after, is tentative. Then there’s the fact that the tears from the baleful speaker do not feel like an exhortation of joy. Instead, they feel like a shaky realisation–a harbinger of separation to come. As if to say, it is nice not to be alone. But things aren’t nice here, are they?

Of course, “The Power of the Dog” is – among other things – about the nature of loneliness. Its final act of tragedy (or deliverance, depending on your perspective) occurs because of a skewed, misguided overture of feigned closeness. Here, in Montana where the story is set, loneliness is survival. Or, loneliness is safety. To a point. Jane Campion has been preoccupied with that for her entire career. This, her first film in twelve years, is a western drama – an adaptation of Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel. Of her earlier work, that concern for the lonely is most overt in her Palme D’Or winning “The Piano” but it bleeds out of all her work, a haemorrhage of realisation that colours Ben Whishaw’s Keatsian desire for closeness in “Bright Star” or Meg Ryan’s flirtations with dangers of masculine overtures in “In the Cut”. The “Power of the Dog” contemplates those concerns, and then turns them into something even more heightened. It’s not incidental that this is the first Jane Campion film that feels truly like an ensemble film. We are not rooted in a central character. There are four main characters here, three more shaded but the entire quartet is pivotal. And four is a promising number. There are sixteen subsets from four. Minus the empty set, heavy with its absence, we can construct the group as each of the four alone. Six pairs. Four triads. And again, the four. If these constructions seem too headily pedantic, “The Power of the Dog” invites a methodical desire to construct, and then deconstruct and then reconstruct. Human against human against human against human.

Of course, “The Power of the Dog” is – among other things – about the nature of loneliness. Its final act of tragedy (or deliverance, depending on your perspective) occurs because of a skewed, misguided overture of feigned closeness. Here, in Montana where the story is set, loneliness is survival. Or, loneliness is safety. To a point. Jane Campion has been preoccupied with that for her entire career. This, her first film in twelve years, is a western drama – an adaptation of Thomas Savage’s 1967 novel. Of her earlier work, that concern for the lonely is most overt in her Palme D’Or winning “The Piano” but it bleeds out of all her work, a haemorrhage of realisation that colours Ben Whishaw’s Keatsian desire for closeness in “Bright Star” or Meg Ryan’s flirtations with dangers of masculine overtures in “In the Cut”. The “Power of the Dog” contemplates those concerns, and then turns them into something even more heightened. It’s not incidental that this is the first Jane Campion film that feels truly like an ensemble film. We are not rooted in a central character. There are four main characters here, three more shaded but the entire quartet is pivotal. And four is a promising number. There are sixteen subsets from four. Minus the empty set, heavy with its absence, we can construct the group as each of the four alone. Six pairs. Four triads. And again, the four. If these constructions seem too headily pedantic, “The Power of the Dog” invites a methodical desire to construct, and then deconstruct and then reconstruct. Human against human against human against human.

Our first image, after the number I appears (the film is divided into five established chapters) is a herd of cows; the cowhands ride around them. Two of the cows come against each other, touching foreheads, either in opposition or in acceptance. That kind of ambiguity defines later moments of human proximity. We leave the cows (they will return, more important than we initially anticipate) and follow a man, striding confidently across the plain. It is Benedict Cumberbatch as Phil Burbank, ranch owner. We watch him from a distance, an immediately beguiling positioning. Our vantage point is inside the house, and we follow him walking outside. He passes a window, and we see him. He walks and the wall of the house interrupts our view. And then he reappears in the next widow. Then, again, he is hidden by the next wall. A man alone, a subset of one. We meet him at the stairs and he stalks into the bedroom upstairs, where he begins a conversation with his brother George (Jesse Plemmons). Brother to brother, a subset of two. Their words suggest engagement – a conversation hearkening back to the past. How long have they been running together? But most of the conversation plays out by emphasising a separation. Phil in the bedroom, George in the bathroom. Together, but alone.

We also meet our other pair divided by a wall. A mother knocks at her son’s door, announcing her entrance. “I’m going to need your room.” She is a widowed inn-owner. As played by Kirsten Dunst, a woman weighed down by sadness that feels endemic. Even when she smiles, her mouth seems downturned. Her son Peter (Kodi Smith-McPhee, all limbs) is lanky and fragile. The two pairs clash when the brothers stop at the inn. George is taken by Rose. Beguiled her sadness. Phil is repelled (or fascinated?) by Peter’s effeminacy. An unhappy union. An unhappy quartet. One set of four. Rose and George soon marry and move to the brothers’ ranch. She adapts, maladjusted albeit, to life on the ranch and a chain is set in motions. Each of the quartet navigating around each other forming, and reconfiguring variations on subsets of that four.

We never see them, all four of them, properly together. Separation, explicit or implicit, defines the subsets in this quartet but the incongruity of the union is central. The clarity of these themes are telegraphed immediately by the film which teems with attention to details. Halfway through the film there’s a striking sequence. Months after we first meet them, Peter – who has been away at boarding school – arrives at the ranch. It is a reunion with his mother, who is not in throes of a newly-married bliss. The moment begins with the other pair, brother and brother divided by a fence this time but mercifully in the same shot. “Well fatso, I think we’re finished,” Phil says to George. He’s talking about the farm-work, castrating cows as George records the information. But Jane Campion is deliberate. Everything here is a symbol. There’s no time for equivocation or subtlety. At that very loaded sentence, a car pulls up in the periphery driving into the space between the two brothers, pronouncing the division. Now, the two brothers are explicitly divided on screen. They turn away from the audience, to the car and George begins to walk to the newcomers. By the time Rose and Peter unpack, they’re sharing the same physical space – across a distance of some yards but all on the same ranch. But not the same frame. The frame can’t hold them all. One is sweet solitude. Two is company. Three is a crowd. Four is chaos.

These character need space, physical and psychic. The film’s title is a reference to the illusion of a dog which the mountains in the distance create. A change of perspective reveals something that does not really exist. In a scene, George struggles to make a simple request for hygiene to Phil. In another, Rose stoops with a bottle of alcohol, as if clinging to life. An accidental duet between Phil’s banjo and Rose’s piano has no suggestions of closeness, but feels dangerous. Proximity to others is not always joyful. In a rare moment of joy, cutting through the gloom of the ranch, Peter and Rose play a game of tennis for onlookers. They are joined by their game but divided by the net. But as soon as characters share the frame (claustrophobically thrust together under the piercing cinematography of Ari Wegner – the discomfort discombobulates) someone begs an escape. The game is short-lived. And we see them, isolated in the frame, each aware of the other’s presence, but struggling to be together. In the one true erotic moment of the film, a cigarette break towards the end, two characters share a cigarette. One lights it, and smokes, puts it in the mouth of the other. Breathe in. release. Smokes it. But even here, never together. They never appear together in the sequence. So we close-up on a face. Too close, forehead and chin cut off. Solitude. But a hand without a body interrupts the frame with a cigarette. Smoke envelopes the frame. We cut to the other party. Gazing back. Formerly disembodied hand finds its limbs. Smokes. Each reacts to the other, but the camera never grants us that union. It’s nice not to be lonely, but things aren’t nice here.

And “The Power of Dog” makes that discomfort manifest. Campion needles at us. In the way she structures her screenplay, and the way she directs her technical team. Jonny Greenwood’s score encourages anxiety and trepidation. Peter Sciberras’s editing deliberately evokes something effortful. Slowly, but slowly, labouring and lingering on moments. Pay attention it tells you. Why? It’ll make sense by the end, and it does. Wegner’s camera moves across spaces slowly, punishingly. What will we see? And how will it be framed? It’s an empathically deliberate mode for Campion, who has never been as explicit as this before with her thematic concerns. Family. Masculinity. Identity deconstructed. What better than a Western to explore this by? The American genre come home to lay bare the isolation of America. Man against man. But also man against nature. Human nature. But also Mother Nature. Flora and fauna. Remember, the cows were the first things we saw. But, significantly. They are not the first thing we hear.

The film disarmingly encourages us to forget our beginning in a way. Visually, we begin with the cows and then the brothers. They establish the visuals of this world. The first image after the “I” of the first chapter appears. But for a few brief seconds, before that first image, we hear before we see. As the credits roll, and the restless music accelerates, the film opens with a voice, “When my father passed, I wanted nothing more than my mother’s happiness. For what kind of man would I be if I did not help my mother? If I did not save her.” It’s a trick because it sets up something the film immediately abandons. Narration does not return substantively in “The Power of the Dog”, but more significantly there’s a liminal temporality to that opening confession. The timestamp, Montana 1925, appears moments after, rather than before. And so the voice, we will soon learn it’s Peter, seems to float in time. Between past and future and present. A promise, but also threat. But to whom? And from what vantage point?

That will also be answered. “The Power of the Dog” leaves no room for ambiguity. It is an equation. Just like the number four has a finite list of subsets (an equation can find a definitive answer), “The Power of the Dog” is an equation and it will work everything out. Methodical. Deliberate. Decisive. Striking. Pulverising. Campion is harnessing her gifts, but also her team, for something exacting. Like the plan revealed in hindsight by a member of the quartet, this is all feels incredibly worked out. If that worked feeling is a bit too overzealous for Campion, it is to the benefit of these themes and these characters. “The Power of the Dog” resonates with clarity and exactitude. The emotional wallops here are stunning, and lasting. It’s excellent film-making.

“How nice it is not to be alone.” We end with an embrace, and a voyeur looking on. Superficially, it’s a look of content and yet we think, is it? At what cost? How nice it is not to be alone. But we are alone, though. And what niceness is there to find in the bleak terrains of this ambivalent world?

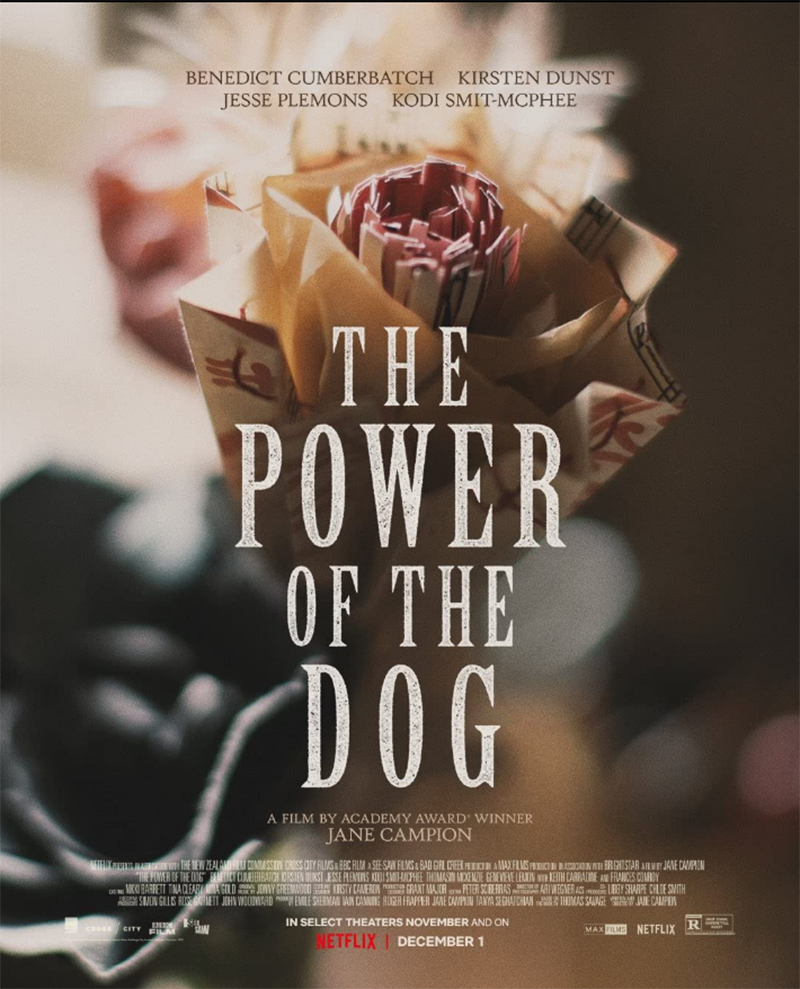

The Power of the Dog is streaming on Netflix