It was the other significant find that pushed Guyana to the top of breaking news in the first year of the pandemic. One cold, grey day in October, 2020, even the most experienced Belgian officers ended up astonished by what they discovered behind the rusting mass of scrap metal in a suspicious shipping container, newly arrived at the sprawling Antwerp port.

Joined in sections, a massive steel box loomed, its sides welded shut. It fitted so snugly into the 20 foot-long freight crate, the only narrow space remained at the top, jammed with a jumble of detritus. Inside the receptacle were hundreds of packages stacked to the ceiling. Big blue plastic bales swathed in tape brought the total estimated find to a record 11.5 tons, equivalent to over 25 000 pounds or 11,500 kilograms (kg) of high quality cocaine.

Days later, the “absolute top catch” was announced by the Belgian Federal Police, following coordinated investigations. They stated in a Tweet that “never before has such an amount of cocaine been found in one sea container” in the European country. Valued at a conservative estimate of €450M or US$530M, but double that when cut for the streets, the historic bust was then the latest advance by the country’s Customs department in its 2020 seizures of 54,543 kg of cocaine. They had intercepted communication in a sting operation, weeks earlier, and were on the lookout for the shipment.

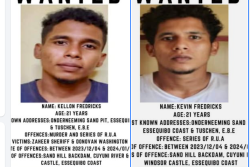

Destined for the Netherlands, the container was among five sent by the local scrap metal dealer and documented shipper, Marlon Primo, formerly of Atlantic Ville, East Coast Demerara, who vanished before international news of the bust, and still remains missing, and on the wanted list. Yet, he was a flashy, small-time figure and a likeable public face and family man locked in a lucrative trade, controlled by what experts call “the rise of the invisibles.”

Antwerp is Europe’s second largest goods port after Rotterdam, and these two cities are now among the top for cocaine trafficking to the continent as the illegal drug business sourced from South America soars to unprecedented and alarming levels in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, with widespread use fuelling violence, corruption and deaths.

For about a year now, the ranks of Guyana’s Customs Anti-Narcotic Unit (CANU) have been supposedly slowly sorting through some 50,000 images, retrieved with outside help, after the photos were deliberately deleted from a Guyana Revenue Authority (GRA) scanner database, in a telling reminder of the pervasive practice of deception within this small society.

No less than the Minister of Home Affairs, Mr Robeson Benn, informed reporters in late December, 2020 that the employee who removed the scans was known, and that related investigations were underway. But he/she has apparently evaporated and any results from the probe are also indiscernible so far.

It is a shameful reflection of the gross inadequacy of the administration’s tepid response that not a single individual has been charged in relation to the crime, or any other cocaine smuggling related offence based on a single of these retrieved scanner images.

With the seizure in Antwerp, there were several more European arrests, including that of a former head of the gendarmerie and three active police officers. Recently, the Dutch, Belgian and Spanish police held other suspects in coordinated raids, associated with the record cocaine bust in the Guyanese scrap metal export scandal.

Netherlands media reported that one of the three Dutch detainees, an “accountant” Joep H., 37, from the southernmost province of Limburg held a major role in the racket, using his financial advisory business based at a former bank building to launder large flows of money for the dealers and traffickers.

Mr H. claims that he was only a minor player, but officials believe that he was also directly involved in the smuggling of the 2,800 kilos of cocaine concealed between tropical wood, in a shipping container sent from Costa Rica in 2019. He was awaiting a decision on whether he will be extradited directly to Belgium to stand trial.

Dutch broadcaster L1 recalled that two years ago, the federal prosecutor’s office started a major investigation, codenamed Operation Costa, into the criminal organisation behind the large-scale cocaine smuggling, not only from Guyana but also Costa Rica, Ecuador and Brazil, among others. In Belgium, nine suspects were arrested in 14 raids, with firearms, cash and vehicles seized. Simultaneously, 13 raids launched in the Netherlands.

However the online site AccountantWeek stated that it “concludes on the basis of its own research that the aforementioned Joep. H. is not an accountant but a tax specialist and financial advisor,” who was part owner of an administrative office.

Predicting that this will be another record year for cocaine seizures, the Rotterdam authorities expect cocaine confiscations to reach at least 60,000 kilos this year, up from the record 41,000 kilos in 2020. Some 90 percent of the world’s cargo is transported in the ubiquitous maritime containers, but on average, due to the sheer volume, a mere two percent is physically inspected by customs officials, making them the ideal smuggling choice for huge amounts of illegal drugs.

The 2021 report, “The cocaine pipeline to Europe,” jointly produced by InSight Crime and the Global Initiative Against Transnational Organized crime, warned that cocaine traffickers have long preferred Europe, which has greater potential for growth and profits than the more saturated United States of America market.

“From a business perspective, trafficking cocaine to Europe is a far more attractive prospect than targeting the US. Prices are significantly higher and the risks of interdiction, extradition and seizure of assets significantly lower. A kilogram of cocaine in the US is worth up to US$28 000 wholesale. That same kilogram is worth around US$40 000 on average and as much as nearly US$80 000 in different parts of Europe,” the report said.

It acknowledged that while European and Latin American governments struggle to contain the pandemic and associated economic carnage, organised crime sees new opportunities, with the cocaine trade now populated by a variety of criminal syndicates, made up of many different and mixed nationalities.

“Criminal networks today rely on subcontracting out much of the work to different transport specialists, assassins for hire, corruption nodes and money launderers, as well as legal actors such as lawyers, accountants and bankers. (They) will align for a particular shipment, then drift apart, searching for new opportunities and trafficking constellations.”

The report noted, “Many of the more sophisticated drug traffickers have realised that their best protection lies not in a private army and extensive security, but rather in keeping a very low profile. These traffickers, whom we call ‘the invisibles,’ make Herculean efforts to remain off the radar of authorities, using brokers and ensuring they have no digital or social media footprint, as well as maintaining a solid legal facade for their business.” Like the “invisibles” in Guyana.

ID hears the words of a senior European policeman, who pointed to the most sophisticated criminal groups feeding corruption. “Corruption is creeping up slowly in Western societies in a way we have not seen before. 10 years ago, if you found a corrupt port official or customs agent, this was huge news. Now it is becoming more common.’