On the anniversary of Martin Carter’s passing, Gemma Robinson asks what kind of writer we find if we look at Carter’s poems about the environment.

Martin Carter’s friend and contemporary, Wilson Harris, once wrote that Carter’s world was characterised by a ‘homing instinct within the wilderness of the Guianas’ whereas Harris’s was typified by a ‘voyaging instinct’. This contrast encourages us to think about how the two writers might journey towards or away from a familiar human-centred world. Carter is undoubtedly a poet of Georgetown and Harris a writer of the interior. However, these classifications are also in danger of trapping two of Guyana’s great writers within an opposition of human vs nature that we cannot afford in our contemporary moment of environmental disaster and uncertainty.

At the recent UN Climate Change Conference, COP26, Caribbean leaders outlined the risk of ‘our common destruction’ and made pledges about reducing emissions. Scientists and activists continue to focus our minds on the costs and consequences of human actions and our possible global futures. These times also call for the empathies and outrages of the imagination. In this age of climate change and environmental crises, Carter’s work helps to remind us of the fragility and complexity of our shared planet.

Here are three things we might learn from Carter’s poetry.

‘Humans are in and of nature’

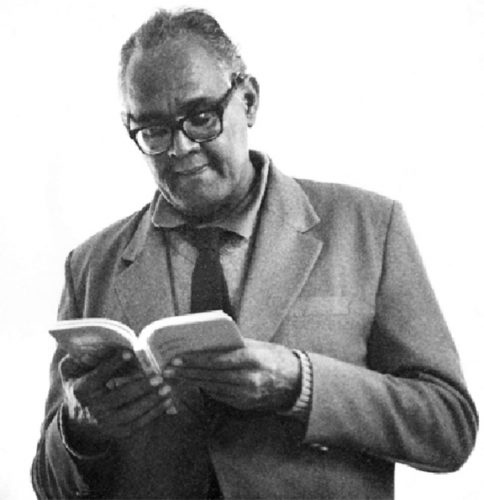

While Wilson Harris’s observation focuses on the powerful ways that Carter’s poetry is attuned to life as it is lived by humans, the artist Stanley Greaves has long recognised that there is more than a human-centred world in Carter’s work. Greaves remembers that hanging in Carter’s study was a print of The Tempest, a landscape painting by the Renaissance artist Giorgione. In his essay ‘Visions of Land and Landscape’ Greaves explains that the painting is ‘an expression of man in and of nature as opposed to man and nature, a distinction that appealed to Carter’.

Greaves also tells the story of Carter imagining the kind of landscape painting he would like to own: ‘it was to be done Chinese style featuring a mountain and a tiny human figure sitting at the base of it’. This image of balance and scale emphasises the relative importance of the human. Greaves continues: ‘Carter always felt that representations of the human figure should not be the major focus in landscape painting. They were just another element in the presentation and people need to know their place’.

The final lines of ‘Three Poems of Shape and Motion’ (1953) are a good example of Carter’s understanding of the human and the idea of ‘knowing their place’. He writes ‘I walk slowly in the wind / I walk because I cannot crawl or fly’. Here what it is to be human is only understandable by its relation to the other beings that inhabit our inseparable world. Carter would return to this idea throughout his writing. In ‘Endless Moment World’ (1970), Carter imagines the complex being required for living in his complex times – a new kind of being made of wind, bird and fish that can survive and even thrive in this place where breathing is hard:

And would not have turned to myself

if language were only sound.

Nor would have made use of the breath

if the wind itself were voice.

So living where to breathe is hard

I fly like a fish in the air

and swim like a bird in the water

and gill stays gill, and lung stays lung

and my fin and my wing help each other.

The word ‘world’ appears a lot in Carter’s poetry – from his earliest work to his last poems. One of his most repeated lines is ‘I do not sleep to dream, but dream to change the world’. Sometimes ‘world’ seems to refer to a human-centred vision of life – the world as people. Sometimes it feels more like a synonym for the earth and the idea of the connectedness of all things on this planet. The final paradoxical image in ‘Endless Moment World’ falls into this second way of understanding ‘world’.

Nature is urban

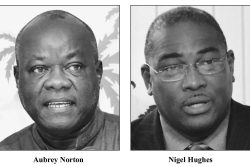

If Wilson Harris provided Carter with a direct link to Guyana’s interior landscapes and ecosystems, his friendships with Aubrey Williams, Denis Williams and Ivan Forrester continued this connection. In his poem ‘Cuyuni’ (1972), Carter faces the untranslatable power of one of Guyana’s great rivers, writing of it as a place ‘far from the noise of language / where gods still live and brood on thrones of rock’. In ‘Rain forest’ (1980) he writes that ‘Every clear raindrop helps to obscure / the green towers’, stressing the entwined ecosystem of climate and forest.

However, what is also striking about Carter’s work is how he does not deny the urban in favour of the wild. He blurs the edges between the urban, rural and wild to undermine strict distinctions between built, cultivated, and apparently ‘untouched’ environments. The concept of the Anthropocene was not current in Carter’s day, but the idea that we are living in a geological age when the actions of humans on this planet are transforming its climate and ecosystems seems to fit with Carter’s plural sense of ‘the world’. The poet who wrote ‘from the plantation earth I cry’ understood the violence and damage that humans can do to each other and their living landscapes.

What we might call urban nature abounds in Carter’s work, from the revolutionary landscapes of ‘Like the Blood of Quamina’ (1951) – that link plantation rebellion and river-side cane fields on the city’s edge – to the familiar contemporary sight of the ‘leaves of the canna lily near the pavement’ (‘The Leaves of the Canna Lily’ (1972)). In ‘We Walk the Streets’ (1974) the poet hears thunder, and lightning becomes ‘a flick-knife / in my mind’s awkward hand’. The poem, ‘In a small city at dusk’, is especially attuned to the ways that urban life might be unravelled to expose the layered forms of existence operating in a single place. The small city is presumably Georgetown, although it needn’t be. Carter begins with a simple observation that as the daylight decreases it is hard to tell the difference between a bird and a bat. This is a quiet poem but its reverberations are profound.

Carter was well-known as a walker, and this feels like a poem written by someone outside rather than someone inside looking out. In the poem, we move between beak and claw and hand, and the environmental consciousness is pronounced:

Stranger to each other they seek

planted by beak or claw or hand

the same tree that grows out of the great soil.

And I know, even before I came to live here,

before the city had so many houses

dusk did the same to bird and bat and does

the same to man.

With a lightness of touch we recognise the affinities between birds, bats and humans and the ecosystem that supports them (they all seek ‘the same tree’ from the same ‘great soil’). Carter imagines a prehistory for this urban landscape and, in doing so, the houses – the fragile structures of human history – seem to dissolve in this poem with the dusk.

Respect your micro-environments

In Carter’s later work from Poems of Affinity (1980), we find a group of poems that are esoterically environmental. ‘If / trees die, what happens to / caterpillars?’ he asks in ‘Too Much Waiting’. His questions articulate a hope for affinity in a world that the poet writes as arbitrary and as fragile as it is random. The main text of each poem in the collection is laid out on the right-hand pages of the book, with the title of each poem centred on the left-hand page. The effect is striking: wherever the book is opened a reader is faced with a single dense poem, often not more than ten lines long and many accompanied by a visual ‘appreciation’ by Stanley Greaves.

Gordon Rohlehr’s sharp evaluation of Poems of Affinity sees Carter as a poet ‘resigned to the barrenness of imagination and the squalor of politics’. However, when we recalibrate the collection to consider the non-human, another horizon opens for the future of social action. Carter’s eye becomes focused, even microscopic, and we discover previously obscured environments.

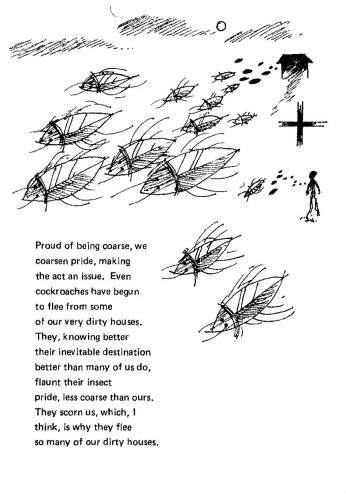

In ‘For Cesar Vallejo ii,’ it is the cockroaches who have more purpose than the humans, knowing their ‘destination’ better than the ‘we’ in the poem. Carter concludes, ‘They scorn us, which, I / think, is why they flee / so many of our dirty houses’. In his appreciation Greaves responds to this reversal of scale. The silhouette of a house recedes into the top right-hand corner as the cockroaches take over the page. But this is not infestation – the cockroaches have an almost jewel-like shape, like a reimagining of the Egyptian scarab amulets that symbolise renewal and rebirth.

In other poems, there are crows, seeds, uprooted trees, green leaf, owl, toad, seagull, shrimp, tick, crab, ants, padi, green pods, ground doves, dogs, kitten, jumbie umbrella, candle flies, parrots, petals, feather. And Carter gnomically dedicated Poems of Affinity to ‘all children, flowers and dogs in that order’. This is not a menagerie for exhibition – each life form is respected within its own context, but threat, uncertainty and extremity are never far away.

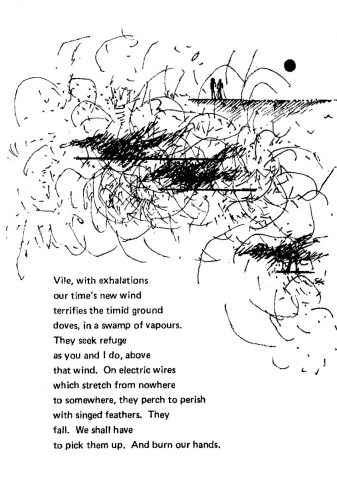

We read in ‘Ground Doves’ that ‘our time’s new wind / terrifies the timid ground doves’, sending them from their habitat of ground cover to the dangerous ‘refuge’ of electric wires where life is deadly:

they perch to perish

with singed feathers. They

fall. We shall have

to pick them up. And burn our hands.

Carter’s initial drafting of these lines reveals the accuracy of language to which he aspired. First he wrote ‘Aghast / Time will pick them up’. In revising the poem, Carter clarifies the nature of human responsibility, obligation and the shared pain that comes with ecological disaster. The costs of ‘our time’ are felt by all, and it is important, therefore, that ‘We shall pick them up’ rather than a notion of abstract ‘Time’.

Greaves’s image of miniature figures placed on a distant horizon poignantly notices this relationship, even as he foregrounds the terrifying experience of the doves. The fine lines of hatching that typify Greaves’s method across the collection become frenzied in this appreciation. The scale of the poem might be a micro-environment but the extremity of the crisis is all-encompassing. In that sense, we all ‘perch to perish’.

The future in Carter’s work is only voiced so far. At the end of ‘Ground Doves’ Carter does not intimate what happens after we pick up the dead birds and burn our hands. What remains is poetic ambiguity. In another poem from Poems of Affinity Carter closes with ‘And / when I see a green tree, / I tremble’. Across his work the colour green is often associated with hope, life and renewal. Here the poet literally shakes like a leaf, connecting human to leaf to tree. However, the connotations of ‘tremble’ pull in multiple directions, encouraging us to think of anxiety, excitement, frailty, fear, dread, and apprehension. This is the advantage of Carter’s ambiguity: all of these responses must be reckoned with and the complexities of this shared environment cannot be forgotten.

In 1990 in his private notebook, Carter wrote: ‘Poetry: a way of surviving: If life is the question asking what is the way to die, poetry is the question asking what is the way to live’. Carter was returning to the final line of ‘A Mouth is Always Muzzled’, but it is the twinned idea of surviving and living that demands attention now. What does survival and the question ‘what is the way to live?’ mean to us? We might remember Carter’s imagined small human figure living in the presence of the mountain and Greaves’s radical rescaling of the human in his drawings. In Carter’s work questions about the limits of human action are productive, reminding us of the diverse powers of the non-human. In our time of environmental crisis we need art forms that are attentive to questions of survival, not just to create the poetry of human life, but to respect and sustain the precarious ecosystems of our world.

Gemma Robinson is the editor of University of Hunger: Collected Poems and Selected Prose of Martin Carter (Bloodaxe Books).