An alliance of Caribbean organisations have objected to the Environmental Impact Assessment (EIA) for the Exxon-led Yellowtail project in the Stabroek Block offshore Guyana, saying that that regional states that could potentially be affected were excluded from the process.

In a December 15, 2021 letter to Environmental Assessment Board (EAB) Chairman Omkar Lochan, environmentalist Simone Mangal-Joly, on behalf of the Caribbean Coastal Area Management (C-CAM) Foundation, The Jamaica Fish Sanctuary Network, the Jamaica Environment Trust, the Institute for Small Islands, Fishermen and Friends of the Sea, and Freedom Imaginaries, also says that the EIA is “significantly deficient” as it fails to establish a baseline economic value of the coastal areas of the Caribbean, including Guyana.

“We therefore call on the EPA [Environmental Protection Agency] to reject the EIA until minimum guarantees are established in Guyana,” Mangal-Joly added in the letter.

In the letter, Mangal-Joly noted that the present Yellowtail EIA process fails to meet basic standards of international environmental law that were designed to protect the planet’s ecosystems and citizens from potentially catastrophic accidents. “Given the failures… coupled with the high-risk nature of the proposed Yellowtail project, we call upon the Guyana authorities to immediately set aside the current EIA process, alert the Governments of the Caribbean of the specifics of the risks posed by offshore oil production, and re-engage with an EIA process that meets international legal obligations and best practice standards for both transboundary consultation and objectivity,” it urged.

The Yellowtail project is ExxonMobil and partners’ fourth development in the Stabroek Block and is considered the largest undertaking since Guyana became an oil-producing nation. As part of the Yellowtail Project, ExxonMobil plans to drill between 40 and 67 wells for the 20-year duration of the investment. It is intended to be the largest of the four developments with over 250,000 barrels of oil per day targeted once production commences. Based on the schedule, once approval is granted, engineering commences in 2022 and production in the latter part of 2025.

However, Mangal-Joly’s letter explained that the EIA process failed to meet basic principles of international environmental law, including the right of potentially affected states to participate in the EIA process and provide and access information on the risk of transboundary harm. “By failing to respect these basic rights, Guyana has excluded Caribbean states and its communities from public debate on whether the risk associated with the proposed project is acceptable to the region and the appropriate measures to prevent or mitigate that risk,” she said.

The letter noted that ExxonMobil’s affiliate, Esso Exploration and Production Guyana Limited (EEPGL) and its partners have been producing oil offshore of Guyana since 2019 in a high-risk deepwater operation at 1,500m to 1,900m depths.

Environmental Resources Management (ERM), an Ameri-can consulting firm registered in Guyana, has conducted all the EIAs for EEPGL for three deep water project developments for which the Government of Guyana has granted Environmental Authorisation: Liza 1, Liza 2, and Payara. This firm was also responsible for the Yellowtail EIA.

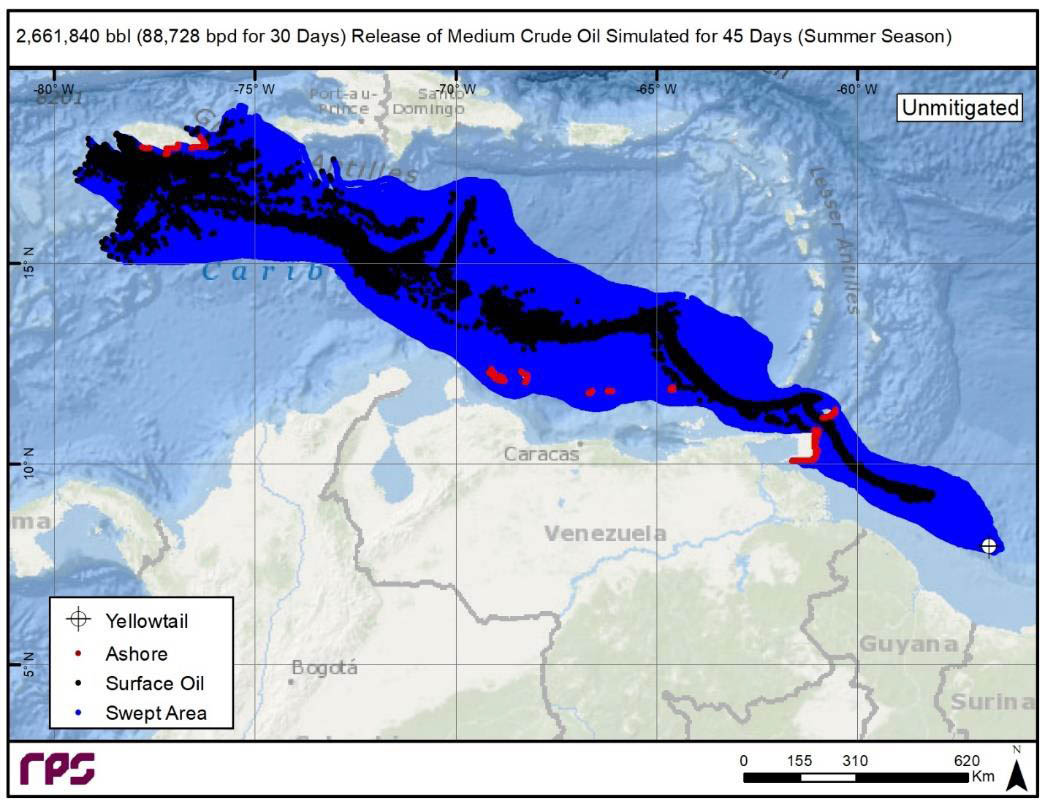

According to the letter, the Government of Guyana, EEPGL and its British and Chinese partners have been aware of possible transboundary impacts of a potential deep well oil spill since the conduct of the first EIA for the Liza 1 development in 2017. “This risk to Venezuela and Caribbean Sea countries was affirmed by successive EIA studies, with the Yellowtail study indicating a potential impact area covering all the Lesser Antilles and reaching as far as the southern and eastern coasts of Jamaica. This is according to ERM’s oil spill modelling, which was done with an unrealistic worst-case scenario that heavily favours the company at an underestimated 30-day spill window. We know the Macondo deep water well took 87 days to control, and at the very least this sets the precedent for a worst-case scenario,” Mangal-Joly points out.

She acknowledged that EEPGL has acknowledged the possibility of oil spill risk and its liability for damages, and that it laid out steps to alert and engage potential transboundary victims in the Liza 1, Liza 2 and Payara EIA studies. The letter also quotes the text in the EIA approved for Liza 1 (2017) setting out how EEPGL would treat with transboundary victims of an oil spill from its operations:

“EEPGL will work with representatives for the respective countries to be prepared for the unlikely event of a spill by:

– Establishing operations and communication protocols between different command posts.

– Creating a transboundary workgroup to manage waste from a product release – including identifying waste-handling locations in the impacted region and managing commercial and legal issues.

– Identifying places of refuge in the impacted region where vessels experiencing mechanical issues could go for repairs and assistance.

– Determining how EEPGL and the impacted regional stakeholders can work together to allow equipment and personnel to move to assist in a spill response outside the Guyana EEZ.

– Assigning or accepting financial liability and establishing a claims process during a response to a transboundary event.

– Informing local communities regarding response planning.”

According to Mangal-Joly, the ERM has copied and pasted this text, with only minor alterations, into Liza 2’s EIA (2018) and Payara’s EIA (2019). “However, this was repeatedly done with no reflection or assessment whatsoever as to whether EEPGL had made any effort to honour the steps it had outlined in the previous EIAs regarding potential transboundary victims.

“Now, four years after the Liza 1 EIA, and two years into oil production, the same text appears in the Yellowtail EIA, with only slight alterations that reduce the scope of EEPGL’s responsibilities to engage only when an oil spill occurs and in coordination with the Government of Guyana,” she said.

The text now reads:

● “Working jointly with the Government of Guyana and, as appropriate, with the government(s) of other potentially impacted jurisdictions to support bi-lateral oil spill response agreements in the region, in alignment with the principles and protocols of the Guyana National Oil Spill Contin-gency Plan. In the event that there is an oil spill incident that impacts areas outside the Guyana Exclusive Eco-nomic Zone, EEPGL—with support and approval from the Government of Guy-ana—will work closely with representatives for the respective locations to:

– Coordinate oil spill response operations and communication between different command posts in the region;

● Create a spill-specific transboundary workgroup to manage waste from a product release—including identifying waste-handling locations in the impacted regions and managing commercial and legal issues; Work with nominated spill response vessel owners/operators to identify places of refuge in the impacted regions where vessels could go for repairs and assistance;

● Determine how EEPGL and the impacted regional stakeholders can work together during a spill res-ponse to allow equipment and personnel to move to assist in a spill response outside the region while still retaining a core level of response readiness within the jurisdictions;

● Determine spill-specific financial liability during a response to a transboundary event; and

● On a spill-specific basis, work with local communities within the impacted areas to raise awareness of oil spill planning and preparations.

Mangal-Joly said except for efforts to develop an MoU with Trinidad and Tobago, neither the Government of Guyana nor EEPGL have alerted our governments with the specifics of the risk shown in the oil spill modeling or invited them to consult, thus enabling them to consult internally with directed affected parties. “The proposed approach in the Yellowtail EIA of engaging us as potential transboundary victims only when a crisis is upon us is prejudicial against our interests. Among other things, it deprives us of the opportunity to participate in preventative efforts and it fails to allow for a fair process for establishing ecological and socio-economic baselines as the basis for damage claims. It is, in fact, a clear violation of our rights under international law,” she wrote, before citing a 2017 advisory opinion by the InterAmerican Court of Human Rights on “The Environment and Human Rights,” as well as a 2015 International Court of Justice judgment on the construction of a road in Costa Rica along the San Juan River.

“To date all of the EIAs conducted by ERM, since as early as 2018, have identified the possibility of significant transboundary harm. Yet, all the EIAs conducted by ERM have failed to identify Guyana’s legal obligations to notify and consult with potential transboundary victims before a project is undertaken,” she pointed out.

Mangal-Joly charged that the decision not to alert other countries and involve the potential victims of a transboundary spill was taken by EEPGL, its consultant ERM, and Guyana’s EPA in full cognizance of international best practice standards on transboundary consultations as she noted that the Yellowtail EIA process commenced under international best practice standards reflected in the Guyana 2020 General Guidelines and Petroleum Guidelines in May of 2021. “These guidelines alerted the companies and Agency as well as stakeholders to the value of transboundary consultations…,” she said.

These 2020 EIA Guidelines, Mangal-Joly pointed out, were consistent with the Environmental Protection Act, which empowers the EPA to require private developers to honour Guyana’s obligations under international laws and conventions. Section 13 (1) (c) specifies: “a developer shall have an obligation to comply with any directions by the Agency where compliance with such directions as necessary for the implementation of any obligations of Guyana under any treaty or international law relating to environmental protection.”

However, she said all four successive EIAs conducted by ERM not only failed to identify Guyana’s legal international obligation but also to acknowledge that Guyana has signed and ratified the Cartagena Convention, which, among other things, sets out the commitments that Caribbean states have made towards each other when it comes to addressing seabed pollution from development activities as well as oil spills.

Mangal-Joly said another major point of concern is that the EIAs openly lack objectivity. “They treat with potential socio-economic impacts primarily as benefits of the proposed investment and there is no proper assessment of potential economic losses to subgroups of stakeholders from the project’s routine activities and potential upset conditions. Nowhere do they acknowledge and establish a baseline economic value of the coastal areas of the Caribbean. For example, the Yellowtail EIA document identifies the Portland Bight Protected Area, Jamaica’s largest protected area, in the south of Jamaica and other sensitive ecological areas, but fails to identify the numerous fish sanctuaries and other important fishing locations that are the ecological and economic base of the island’s fisheries industry. Additionally, there is the Kingston port through which millions of dollars of business is done daily, important coastal tourist areas, and mangrove forests that provide protection in lieu of millions of dollars that would have to be spent for built defence structures to protect the island from storms. There is no effort to assess the socio-economic baselines and potential economic losses even to Guyana, the host country,” she added.