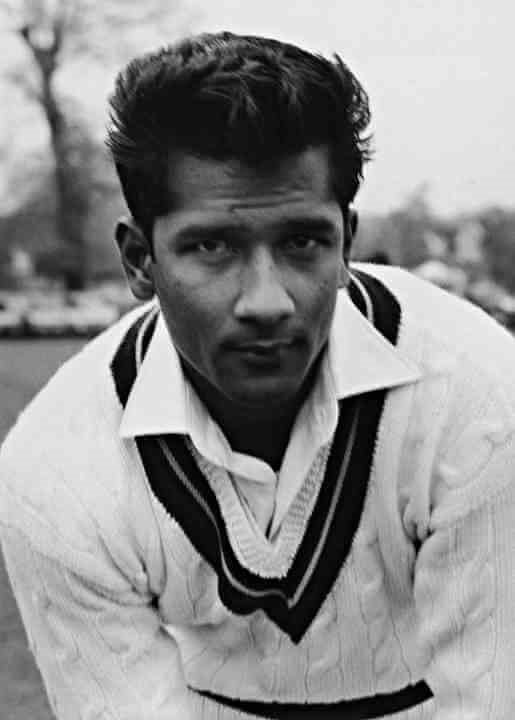

When Kanhai came out to bat there was that sudden, expectant, almost fearful, silence that tells you that you are in the presence of some extraordinary phenomenon… – Ian McDonald.

In the early 1970’s when I was at primary school in Guyana, there was a story going around about a great West Indian cricketer. It was a tall tale, an anecdote intended for juvenile consumption, it told of Rohan Kanhai batting at the Bourda cricket ground in Georgetown and how he hit a ball to Berbice, some sixty miles away. There was a non-glamorous and straight version of this event; Rohan launched a ball over the Regent Road side-screen, and it landed in the tray of a passing lorry, which went all the way to Berbice. However, to the enthralled youths of that era, some of us blessed with naivety, the fabled version was preferable, to them Kanhai was indeed capable of such superhuman feats.

Nothing was beyond our larger than life hero from Port Mourant estate, he was a Bunyanesque figure who bestrode the cricket fields around the world, bossing the best bowlers and ruling the radio waves. When he was in his element, cricket was indeed, lovely cricket and his flashing blade became a constant source of pride and lore; which other batsman could lie on his back on a cricket pitch and smash a fast bowler over the boundary for a six.

I was never a fortunate witness to the audacious and entertaining Rohan in his prime. It was until the mid-80’s , a decade after he retired from the game, that I saw the gray-haired veteran play a brief cameo in a friendly match at Bourda. In the new millennium, the age of internet offers a few videos mostly black and white, to the Kanhai aficionado. However, those experiences are like devouring a tantalizing hors d’oeuvre and then denied the rest of a seven-course dinner. I am famished for words, to do justice to his brilliance. How do you catch a blazing comet that has passed and place it in a bottle? Hence, I am beholden to those who saw him at his dashing best, and wrote about it.

Among the privileged was the esteemed author Ian McDonald, who first saw Kanhai in 1956 and was smitten since by the young genius , his words convey unbridled adoration: “When Kanhai was batting, every stroke he played, one felt as one feels reading the best poetry of John Donne or Derek Walcott or listening to Mozart or contemplating a painting by Turner or Van Gogh or trying to follow Einstein’s theory of relativity – one felt that somehow what you were experiencing was coming from “out there”: a gift, infinitely valuable and infinitely dangerous, a gift given to only a chosen few in all creation”. At the receiving end of a superb Kanhai double century, the Pakistani captain Abdul Kadar, an accomplished cricket writer did not mask his wonderment: “Kanhai’s batsman ship spoke of the thunder and told of the blood-shaking of his heart. The innings was existence itself and presence at the ground a privilege.”

Kanhai’s intrinsic talent and swashbuckling batting brought a different dimension to the game; Wisden Almanac described him as “playing shots never before seen on a cricket field”. In a way, he was before his time, a forerunner of cricket’s innovative strokeplay now mushrooming in white ball cricket; before the dill-scoop, the switch hit, the ramp shot or Dhoni’s helicopter there was Kanhai’s “falling hook.” It was a stroke of pure originality and refreshing boldness, paradoxically tagged by the great English writer Neville Cardus as “the triumphant fall”.

It was a triumph indeed, graphically described by his fellow Guyanese, the historian Clem Seecharan: “A cross between a sweep and a hook, Kanhai was usually off the ground as the horizontal blade crashed savagely into the ball, and with a free flow he would settle on his back, the bat aloft, his head off the ground, his eyes frozen, pursuing the retreating ball into the crowd beyond the backward square boundary as the ball swirled for six and Kanhai airborne, landed on his back.”

He did not possess the elegance of Worrell, the versatile genius of Sobers nor was he the intimidatory tamer of attacks like Richards; he was not a Lara, the left-handed slayer of spinners or a tireless, doughty opponent of bowlers like Shiv, yet he has a hallowed place in West Indies cricket. He resides in the collective psyche of a people as no other, for the greatness of Kanhai cannot be quantified in style or substance, how do you measure that essence, that spirit that embodied the game and gave it that West Indian flair.

The writer CLR James of Beyond a Boundary fame , was an astute analyst of the Kanhai phenomenon and describes it best “….in Kanhai’s batting what I have found is a unique pointer of the West Indian quest for identity, for ways of expressing our potential bursting at every seam”. He went on further to suggest the reason why the flashing blade of the Berbician blaster would earn him a special place in the annals of the sport, for he was “ …a West Indian proving to himself that henceforth, he was following no established pattern but would create his own. And that Kanhai was, “reaching the nether regions never touched by Bradman.”

The Guyanese batter came on the scene, during an important chapter in the socio-political history of the region, the 1950’s was a turbulent time as colonial shackles across the British Empire were being smashed, the reverberations resounded in the West Indies, where a new social consciousness awoke. In Kanhai’s homeland, Cheddi Jagan, another endeared son of Port Mourant, was leading a grassroots populist movement that challenged the entrenched interests of the sugar barons and the colonial authorities. Kanhai was a product of his time when, “Cricket is an art, a means of national expression”.

Blasting

In his autobiography, appropriately titled Blasting for Runs, he outlined his own creed, “The way I see it, I’m paid to hit any and every bowler as hard and as far as I can. Nobody said anything about how I have to do it”. The see ball, hit ball attitude and unorthodox strokeplay have won him legions of fans around the world .There is a pub in Ashington, Northumberland, in the northern England named, The Rohan Kanhai – I don’t know of any other cricketer to be so honoured .Even his contemporaries, fierce competitors on the field paid him homage, Ian Chappell described Kanhai as “one of the best right-hand batsmen I’ve seen”, Benaud echoed that praise: “one of the finest batsmen the world has seen.” Michael Manley wrote: “No more technically correct batsman ever came out of the West Indies than Rohan Kanhai”. However the ultimate tribute came from his admirers, among them the Indian opener Gavaskar, Kallicharran, Aussie leggie Bob Holland and reggae great Bob Marley, all them named their sons – Rohan. Rohan, a name bestowed on a baby boy, born on Boxing Day in 1935, it is a word taken from the lexicon of his ancestors and it translates roughly to “ascending”. For the East Indians of the then British Guiana, many domiciled on the sugar estates, still on the social fringes of BG society a century after their boats landed , that word was not just semantics. For them it was a tangible act. Rohan and his rise to prominence on the cricket field became a personification of their own hopes and ambitions; he also was from a sugar estate, he too faced the same travails and stigma of a rustic life and like them, he too was an East Indian.

His grandparents were among the multitudes of ‘coolies’ transplanted from the thousands of villages and towns spread across the vast plains of subcontinent to the British Guiana, for the sole purpose of turning the wheels of the sugar industry. Some returned to India at the end of their contracts, for those who chose to remain in their adopted land, cricket became a pastime of plantation life. Their early involvement was marginal and like the blacks before them, they often assumed the role of the passive spectator. Once the Indians moved away from the constraints of the plantations and settled in villages adjoining the sugar estates they became more participatory.

The village green and any open piece of land was transformed into a cricket field. D.W.D. Coming, an immigrant advocate who visited British Guiana in 1891 reported: “Many of the sons of the East Indians born in the colony play cricket regularly. On Saturday afternoon on most estates, a game can be seen going on, the player being partly Creole coolly boys and partly black and the game are played with Great Spirit. Many managers encourage them to play, and some even get up rival matches with neighboring estates.”

Not much is known of him but on 18th January 1909, P. Gajadhar a left arm spinner became a historic figure when he bowled for Trinidad against Barbados in the Inter Colonial Tournament Final. He was quite possibly the first cricketer of East Indian extraction to play inter- territorial cricket.

The following year, Joseph Veerasawmy and Paul Ouckram debuted for British Guiana and these three became the forerunners, as during the 1920’s and 1930’s Indians became more visible in the territorial teams with the likes of Richard Rahomon, Charles Pooran, Abdul Hamid, Korban Razack, DR Mohabir and Sydney Jagbir representing British Guiana and Trinidad at the colony level. East Indians however remained on the periphery of regional cricket as the WI cricket team was still dominated by whites, coloureds and blacks.

Their path to regional recognition and selection was often difficult and elusive. In 1937 an unknown right-handed batter from Demerara; Chatterpaul “Doosha” Persaud stroked a fine 174 at Bourda against Barbados on his first-class debut. In the next match, he accumulated 128 runs and took six wickets as BG won the Intercolonial Final against Trinidad. He was called to trials for the WI team but could not repeat his performances of the previous year and despite having an atypical First Class average of nearly fifty, he was not included in the regional team and was never given another opportunity to prove himself. The glass ceiling was finally shattered in 1950 when Sonny Ramadhin, a rookie off spinner after only two FC games, was selected to tour England and made a sensational debut; he was followed seven years later by Rohan Kanhai.

In his autobiography, Rohan narrates his early beginnings and aspirations; he captures it perfectly with this succinct line: “I never doubted my batting ability from the day I could hold a piece of wood between my two small hands…” He further details the role of Sir Clyde Walcott, in whom the cricketers from the backwater sugar estates and villages of Berbice found an advocate .Henceforth the raw, burgeoning talent of Kanhai, Solomon, Butcher, Madray , Baijnauth and others from the Ancient County could no longer be ignored, could no longer be contained.

In 1956, in his second FC match Kanhai hit a century off a Jamaican attack that included Gilchrist and further distinguished him with a wonderful 195 in his next match against a stronger Barbados lineup. He was called to trials to select the 1957 touring team to England. In two matches, he scored 62 and 90 and blasted away the barrier that previously deprived Doosha Persaud from reaching a higher echelon. Kanhai booked a passage on the boat to the Mother Country and became the first of his kind from BG to wear West Indian colours.

On a bright Wednesday morning in late May, clad in his keeper’s pads and with the weight of history on his slender shoulders, surrounded by Weekes, Worrell, his mentor Walcott, Sobers and Ramadhin the Berbician walked onto the Egbaston ground. He was soon in the action, catching Brian Close off the pacer Gilchrist. A rampant Sonny then bamboozled the English batters and in the late afternoon, Kanhai was walking out again, this time with bat in hand, to begin the WI reply. In the second over his compatriot and opening partner Pairaudeau was yorked but the debutant showed he belonged on the big stage, against the most potent bowling attack in the world, he cracked eight fours and at the end of the day’s play, he was on an undefeated 42. He didn’t add anymore and was dismissed first ball on the second morning .He made just a single in the second innings and accumulated 205 runs in the series with a highest of 47 and a moderate average of 22.88. None of his teammates averaged above 40, as they faltered against Trueman, Statham, Lock and Laker and the WI suffered heavy defeats in three matches of that series.

Kanhai during the 1960’s, along with Sobers, became the bulwark of the regional side and was universally recognized as one of the best batsmen in the world. By the end of that decade, he became one of the fastest batters to reach 5000 runs. He showed he was as good at home, as abroad and scored 50 percent of his runs on foreign pitches, with a touring average almost as good as his average at home. In 1973, he took over the reins of the regional team, the first East Indian to do so and under him, the WI emerged from the doldrums and began to win again. His Test playing days ended against England in 1974 at the Queens Park Oval, when he was stripped of the captaincy in favour of Lloyd, for the upcoming tour of India. He was not included as a player for that tour, although he indicated his availability.

A year later, now nearly 40, a resilient and magnanimous Kanhai turned out for the WI in the inaugural Prudential World Cup, after Sobers who was originally picked ahead of him ,became unavailable. He played a few cameos in the preliminary stages and then in the Final at Lords, showed the value of experience and of an astute cricket mind. The WI was in some trouble, against the Aussie pace quartet led by Thomson and Lillee, when he arrived at the crease. He stowed his explosive shots, dropped anchor and settled the nerves of his teammates in the pavilion and in the boisterous, overflowing stands crammed with West Indian supporters.

Steadied

The WI ship was soon steadied, he ensured no other wicket fell at his end, even as he stayed scoreless for some eleven overs but his reassuring presence at the crease allowed Lloyd to launch a counterattack. Kanhai eventually got going with a searing square drive off Thomson, the first of eight boundaries as he churned out a fifty, slow by his own scintillating standards. The vital 149-run\ partnership with his skipper, who scored an explosive hundred, enabled the WI to reach a decent and as it transpired a winning total.

In a seventeen-year career, in 79 matches played all around the globe, Kanhai produced many gems, among them were the twin centuries at Adelaide – one of those a dazzling 117 made in two and a half hours, a glorious hundred at the QPO in 1968 for a losing cause, a crushing 256, his maiden Test century, when he stamped the pride of India’s best bowler Gupte into the Kolkata dust, after the legspinner called him a bunny. He followed up with a masterful 217 at Lahore against Fazal Mahmood, the king of swing who dominated the WI previously on the matting wickets. Both of these double centuries are still the highest scores by a WI batsman in India and Pakistan.

However, two innings epitomized the greatness of Kanhai; two innings, different as cheese and chalk, one depicted Kanhai the swashbuckler, the other showed that he could also be a battling saviour. The first was at the Oval, when he returned to England in 1963, now styled by Wisden as: “Quick of eye and foot, he times the ball almost perfectly when executing a wide variety of strokes, some of which border upon the audacious, and at his best he can master the most formidable of bowlers”. It was the final match of the series, he had a knee injury , and was advised by a specialist not to play but to undergo an immediate operation .He eschewed all caution and in the second innings of that match with the WI needing 253 to win, he put on a glorious display, it was a sight for the gods, he took on his bowling nemeses of the previous tour and carved a buccaneering seventy-seven made in even time, during which he executed his famous falling hook, and set the WI on the road to victory .

The other was an atypical back-to-the-wall century against the greatest spin attack of the seventies, an effort that saved the WI from certain defeat at the Sabina Park. It was 1971, Kingston in Jamaica, on a moist, seaming track the Indians made a disastrous start and were tottering at 75/5 but they recovered and posted 387 due to a fighting double century from Sardesai and an equally crucial fifty from Solkar. The spin trio of Bedi, Prasanna and Venkat then wrecked the Windies first innings, in which Kanhai top scored with fifty. In a surprise move, the touring skipper Wadekar proudly asked Sobers to follow-on, a first against India.

At their second turn, the home team was in early trouble at 32/2, there was a day plus a session to go and the Indian spin trio were revved up, high in confidence after the WI first innings debacle. A half century by Lloyd and then a ninety by Sobers aided in the rescue effort but it was Rohan, enduring muscle cramps and tiredness who battled through the day to the very end and in the process made his highest Test score at home. It was a marathon, uncharacteristic innings, replete with defense and tenacity but he entertained the crowd with some vintage explosive shots, including his trademark falling hook. With the game saved, play was called off and scores of grateful Jamaican spectators surged onto the field; he was surrounded, hoisted on their shoulders and carried triumphantly off the ground.

Such was the incongruence and majesty of Kanhai, on occasions a dour, defensive fighter but whose entrance onto a cricket field can also empty the bars, as his “arrival to the wicket heralded both hush and expectancy”. Some may tag him as a flawed master, whose spontaneity and innate desire to hit the leather off a cricket ball, led him from the path of “assured and true greatness”. Others may argue that Kanhai was never destined to achieve momentous landmarks or to reign supreme in the cheerless dominion of cricket stats. Perhaps he was ordained for another purpose; to provide stupendous joy and create memories for cricket lovers around the world, memories that would endure long after the stumps were drawn and the applause has dwindled into silence.

However, his greatest legacy is to the people of Guyana; to them he was a champion, a legend with a willow blade who slashed a path so others could follow. His destiny was to be a hero to a people, in a time when heroes were scarce.