Some people remember the first time

Some can’t forget the last

Some just select what they want to from the past

– Mary Chapin Carpenter, “Come On Come On”

In 1992 Mary Chapin Carpenter released her album “Come On Come On”. It spawned seven hit singles but the album’s title track was not one of them. Instead, it served as a pleasant closing song, its vaguely upbeat arrangement a bit out of touch with the beseeching lyrics. But four years later, at Carnegie Hall, Betty Buckley spun Carpenter’s song into something miraculous – something sparer, melancholier and better. With her long-time arranger and musical director Keny Wener and musical director Paul Gemignani, Buckley gave Chapin’s lyrics a home in a new searing arrangement, and the repeated pleas of the speaker to partake in the act of remembrance felt fittingly haunting now: “Come on come on, take my hand / Come on come on, you just have to whisper / Come on come on, I will understand”.

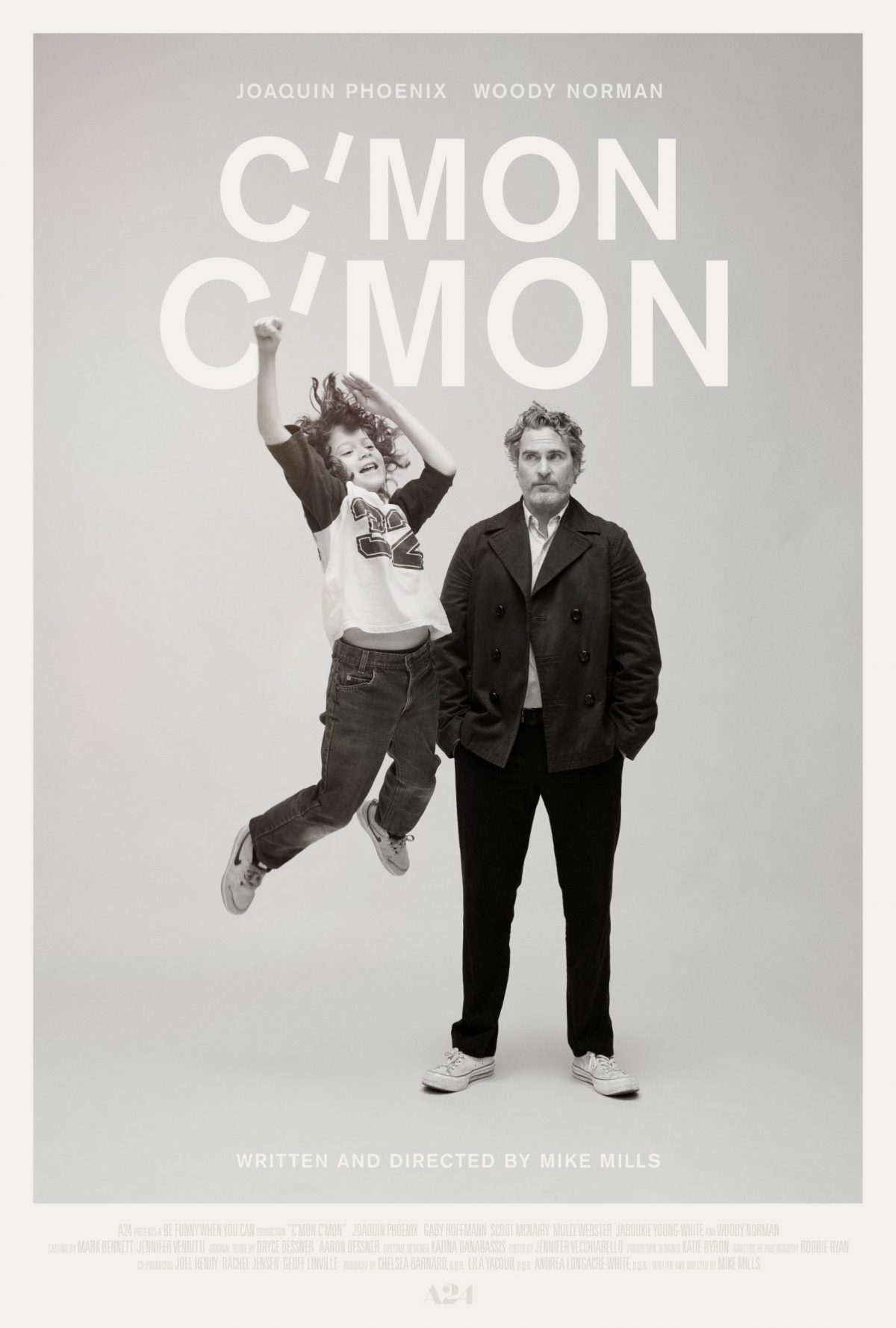

Mike Mills’ new film “C’mon C’mon” (as differentiated from “Come On Come On”) has nothing to do with Carpenter’s song; they just happen to have similar titles. But I’ve been thinking about the echoes of wistfulness in Betty Buckley’s rendition since I watched Mills’ film earlier in December. Both are about memory and how it comes: in waves, by choice or by chance. Mills’ work has always shown great care for memory, and how it mutates. Some might call it nostalgia, although that description feels unapt for the complications of his work. That particular word was bandied about for his last film “20th Century Women” – constructed from anecdotes of his childhood with his mother in the late 1970s. Memorialising runs through his career, though, all the way to his 2001 documentary on paperboys in Stillwater, Minnesota, which found him capturing the lives of paperboys with an elegiac grace that seemed incongruous with the field. His characters always feel as if they are existing in minor keys, sacred in the face of normality. Even the great big things that happen to them are seen through a gaze askance, but never really the focus. It’s the kind of independent filmmaking that gets introduced as quirky, too gossamer thin or too warm or too kind to be really revolutionary or to be listed in the annals of “great” filmmakers, at least not in their time. But Mills is exactly the kind of filmmaker whose gentleness, matched with sharp acuity, might reveal itself as indelible to 21st century American filmmaking when we construct this era in our memories, sometime in the future. He is a filmmaker made for memories.

In “C’mon C’mon,” the legacy of memory is at the forefront of the film, even more explicit than in Mills’ earlier work. Unlike his previous two films, it is set completely in the present, the few flashbacks only go as far back as the previous year. It follows a few sequences of uncle-nephew bonding between Johnny (played by an excellently restrained Joaquin Phoenix), a soft-spoken radio journalist, and Jesse (British-actor Woody Norman, unpredictable and wonderful), his precocious and unpredictable nephew. Johnny has been out of touch with his sister Viv (Jesse’s mother) for a year since their mother, a dementia patient, died. When Johnny reaches out to Viv very early in the film, broaching the separation, she has other things on her mind. Her estranged husband is struggling with mental illness in his new home and she needs to take the trip from Los Angeles to Oakland to help him adapt. Can Uncle Johnny step in? “C’mon C’mon” will build from the misadventures of uncle and nephew as the two learn to understand each other. Preceded by two films explicitly about himself and his family, it feels strange to say that “C’mon C’mon” is the one that gets to the heart of something that has been haunting Mills across his feature-film career – a capital “R” Romantic engagement with what it means to be a person. What does it mean to construct our identities? How do we choose which memories to build from? In short – how does a person be?

In “C’mon C’mon,” the legacy of memory is at the forefront of the film, even more explicit than in Mills’ earlier work. Unlike his previous two films, it is set completely in the present, the few flashbacks only go as far back as the previous year. It follows a few sequences of uncle-nephew bonding between Johnny (played by an excellently restrained Joaquin Phoenix), a soft-spoken radio journalist, and Jesse (British-actor Woody Norman, unpredictable and wonderful), his precocious and unpredictable nephew. Johnny has been out of touch with his sister Viv (Jesse’s mother) for a year since their mother, a dementia patient, died. When Johnny reaches out to Viv very early in the film, broaching the separation, she has other things on her mind. Her estranged husband is struggling with mental illness in his new home and she needs to take the trip from Los Angeles to Oakland to help him adapt. Can Uncle Johnny step in? “C’mon C’mon” will build from the misadventures of uncle and nephew as the two learn to understand each other. Preceded by two films explicitly about himself and his family, it feels strange to say that “C’mon C’mon” is the one that gets to the heart of something that has been haunting Mills across his feature-film career – a capital “R” Romantic engagement with what it means to be a person. What does it mean to construct our identities? How do we choose which memories to build from? In short – how does a person be?

*****

Johnny’s work as a radio journalist gives “C’mon C’mon” its loose structure. He travels around the U.S., interviewing children on their perceptions of the world and soon Jesse becomes part of that structure. The child interviewees meld into the more narrative-bound interactions between Johnny and Jesse, needlingly investigating what it means to be a child in this precarious world. Their answers are thoughtful, surprising, sharp and unusual revealing private struggles. Both Johnny and Jesse are also dealing with their own private struggles. But Mills declines to paint them as exactly the same. Cinematographer Robbie Ryan takes pleasure in framing them in juxtaposition in some of the film’s most striking tableaus – not completely different but not the same. The uncle-nephew relationship is an extension of the mother-son and father-son dynamics of Mills’ previous films, but it’s not a repetition, or not a repetition of those patterns, at least.

Mills opens the film with the framing device that will be repeated throughout. Johnny and his team meet a new interviewee, and open with a series of repeated questions: “When you think about the future how do you imagine it will be? What will nature be like? How will your city change? Will families be the same? What will stay with you and what will you forget?” The last bit, the bit about memory, is the important part. When the idea of memory is invoked in most film, it’s oftentimes in films that are about the past; films explicitly engaging in a kind of reaching back that comfort you with the notions of recognising what the world felt like then, or what the past feels like now. 2021 has seen many of that kind. It’s the kind of reaching back that Pablo Sorrentino does excellently with the roving camera in “The Hand of God” and Kenneth Branagh a little more self-consciously this year in the less impressive “Belfast”. Filmmaking is about bringing the past to the present. But “C’mon C’mon” isn’t feeding us memories. Instead, Mills is asking us to partake in the ceremony of making memories. In the now. Present tense.

Because Johnny and Jesse have not seen each other in some time, Mills is able to filter some much-needed exposition through these catch-up moments. Recent memories play over conversations, or elongated moments of silences, as Jennifer Vecchiarello’s editing stitches the past into the present with a deliberately dreamy quality. The black-and-white cinematography helps with the dreaminess. Temporality is interrupted as memories are made and unmade. But even the exposition feels reticent and accidental, typical of Mills. Yes, there are real moments of pain that resulted in the schism between Johnny and his sister Viv but Mills never really focuses on that even when he’s nudging at them. When “C’mon C’mon” delves into the crises at the root – Johnny’s previous unsupportiveness with Viv’s estranged husband Paul and his mental illness (Scoot McNairy in an excellent, mostly silent performance); Viv’s resentment and frustration of Johnny’s carelessness, amplified by his place as their mother’s favourites; Johnny’s unresolved feelings for a former partner who haunts him in the present – they are not centred, but inform the smaller details Mills cares about. The camera does not mine these crises for expected arguments, instead we have moments like Gaby Hoffman as Viv (who spends much of the film on the phone) holding back a sob for a beat too long. Or the camera focuses on smaller details like Norman’s tiny hand lingering on Phoenix’s nose as he sleeps, or on Phoenix’s hands playing with his hair or his glasses to play off a moment of discomfort.

Mills establishes a rhythm between Johnny and Jesse that lets the structure of “C’mon C’mon” play out as a series of anecdotes from the experiences between the two over the course of their time together. Each anecdote is punctuated with a kind of a lesson, or edification, sometimes very explicitly in the form of a book Johnny reads. Johnny introduces Jesse to his co-workers, who are charmed by Jesse’s precociousness. Johnny loses Jesse in a store and yells at him. Johnny attempts to send Jesse back to his mother and then relents. Late in the film, Johnny reads from “Star Child”, a children’s book by Claire A Nivola – it’s the sequence that introduces the climactic last act of the film where the act of memorialising becomes explicit. As Johnny reads the climax of that book to Jesse, images of the past and present (and perhaps even the future) blur over us. “Over the years you will try to make sense of that happy, sad, full, empty, always-shifting life you are in.”

With “C’mon, C’mon” Mills is making sense – in real-time – of those happy, sad, full, empty feelings. The interviewees punctuate these moments of understanding in ways that introduce them, on the surface, as “lessons”. But this is no twee rumination on growing up; nor, the kind of generic “film we need right now” to show us how empathy works on the screen. Mills is empathetic – it’s part of his filmic marrow. But his empathy is predicated resistance to telling us all the secrets these characters carry within them. A game Jesse plays where he imagines himself as an orphan is left deliberately underexplained. Just as Carpenter sings about selecting what we want to from the past, these people curate what they wish to reveal from their lives. And, in that same way, “C’mon C’mon” feels like a curated assemblage of moments stitched together with good faith and sharpness. They are ambivalent and unresolved but careful and full of clarity – the work of a filmmaker at the height of his talents.

*****

Near the conclusion, Mills finally introduces the scene that establishes the title of the film. It’s a small and beautiful moment I won’t spoil. But in that scene, as the title – now dialogue – echoes over and over, “c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon, c’mon,” the film begins to recognise the subtle hints that have been planted from earlier on: memory-making is not an event that comes with being still; memory-making comes in its movement. You have to live life to remember it. You cannot wait. Even as the Johnny and Jesse act as the centre, the camera is moves beyond them, extending generosity to characters that appear briefly. Time goes by with a deceptive weightlessness in “C’mon C’mon”. It’s a kind of mystical unreality that makes you wonder: how did we get from there to here? Mills’ charm is in as much in the revelations as it is in the secrets.

In a trip to New Orleans, Johnny and his team interview 9-year-old Devante Bryant. Asked to explain the tattoo on his arm, he charmingly refuses and the adults laugh. One of the crewmembers praises his insistence on this privacy: “You know what I appreciate about you? I appreciate the fact that you hold what is sacred.” If you sit through the credits, you’ll see the film is dedicated to Devante. He died earlier this year, weeks shy of his tenth birthday, to gun violence. It’s a reminder of that ephemerality of life that “C’mon C’mon” cares about. How to make sense of this sad, empty, always-shifting life? You hold on to what is sacred. And Robbie Ryan’s camera treats every moment – especially the little ones – like something sacred. Making memories is an act of commemoration. Things go on. Sadness filters through and we urge each other to “c’mon, c’mon”. Forwards and backwards. To the future, but also bringing the past with us.

I spent most of September to early December with my niece, who is seven. Earlier in the month I showed her some photos from when she was younger. She responded in astonishment and wonder, as children tend to do when confronted with their past selves. “I don’t remember that,” she exclaimed at one of images. I explained the moment to her. “Oooh, I remember now,” she acquiesced, a few moments later. I’m not sure that she did remember or if she was responding to my urgings. “C’mon C’mon” plays around with this uncertain reality. The moments we cling to with the children around us might be forgotten when they grow older. No matter how sincere. How do you tell a child, in the moment, this might matter more to me than to you in the future? And how to even abandon the limits of thinking our memories hold on to what we need.

When Johnny’s mother forgetfully asks for her father in a scene, her forgetting has not rendered her love for her children lesser. Nor has it made the hurt they have experienced with her immaterial. Memories come and go, beyond us. But we can’t remember everything. The things we experience do not disappear when we do not remember. “I’ll remind you”, Johnny says at the end. He’s talking to Jesse but he’s thinking and her lost memories, too – a hopeful promise, a slightly desperate invocation to hold on this moment as if to say, “Let me make this moment last just a little longer.” Just in that soft way Betty Buckley plaintively crooned over and over at that Carnegie Hall concert in 1996: Come on come on, come on come on, come on come on, come on come on, I will understand.

C’mon C’mon is available on Prime Video and other streaming platforms