A famous actress is cosmetically and sartorially transformed into a famous historical figure. The historical figure isn’t inherently very similar to the actress, but the ostensible incongruity of the pair, placed in juxtaposition to each other, opens up possibilities. The film, by way of the actress, will excavate a moment in the past, bringing it into the present to tell us something about then but also about “now”. I could be talking about any number of 2021 films (“Respect”, “The Eyes of Tammy Faye”, “House of Gucci”) but this specific foray is about Nicole Kidman in “Being the Ricardos” and Kristen Stewart in “Spencer”, two buzzy recent releases that tread familiar paths of famous women playing famous women. Although ambitious in different ways, neither film manages to become a consistently successful reflection of the lives of real people on the screen. But whether in the immaculate and hollow “Spencer” or the busy and inconsistent “Being the Ricardos”, the women at the centre feel instructive to the fates of the films.

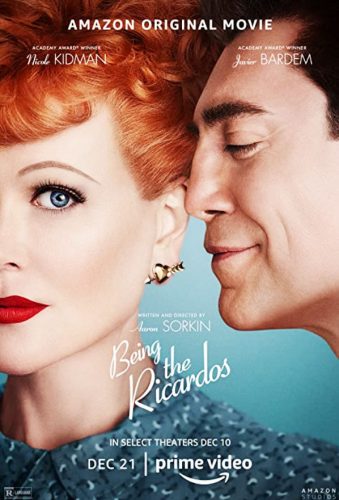

Lucille Ball and Desi Arnaz in “Being the Ricardos”

Art will come and go, but the movie biopic lives on forever it seems.

Endless parades of artists pontificating about how some past event really resonates with Our Present Reality can be exhausting after a time, but there is value in thinking of how the past reflects (and refracts) on to the present. It is why biopics are generally at their best when they engage with a particular aspect in the history of the protagonist; a single crevice in a larger structure of a life. And in that respect, both Pablo Larraín’s “Spencer” and Aaron Sorkin’s “Being the Ricardos” could be immediately compelling. At least in theory. Both films, rather than following a Dickensian birth-to-death format, zero in on a specific moment in the lives of Princess Diana and Lucille Ball to present very different stories about women in the public eye. In “Spencer,” scriptwriter Steven Knight imagines a few days over Christmas in 1991 where Princess Diana begins to unravel in the oppressive company of her in-laws. In “Being the Ricardos”, Sorkin’s script focuses primarily on a week in 1953 when the success of “I Love Lucy” is threatened by a report that Lucille Ball is a communist.

I’m sympathetic to the plight of the much-maligned historical biopic, although that sympathy is often more out of academic interest in the intersections of history and narrative than it is with individual entries. But the descriptor “biopic” often feels like a nonstarter. To imagine any film that features a protagonist who existed as a biopic reveals a nebulous conceptualisation of what a “genre” is. And so many films fall into this casual grouping that it’s no surprise the makeshift genre is judged by its worst offenders. But those worst offenders are plentiful, and oftentimes popular and wildly different. For casual viewers, a biopic can present an easy window into history. They are film narratives uncovering, or retelling events of the past. Audiences get the illumination of an essay or history book with the visual supplements. For performers, I’m less sure what the draw is. One might imagine, when the real person is very famous, it scratches an itch of embodying someone very notable. There is some kind of fascination with being a famous person embodying another famous person. It would explain why every year we watch an endless parade of stars and directors on seemingly endless press cycles drawing parallels to some historical figure reclaimed for the here and the now. But to what end? Why a biopic of this person in this time?

In “Spencer,” our first meeting with the princess, after a brief prologue where we see the Royal family’s Sandringham estate being prepared for the holiday guests, takes pleasures in the biopic as an act of spectatorship. Diana, en route to the estate, finds herself lost and stops at a café to enquire for directions. Claire Mathon’s camera (austere and stately) shoots Stewart like something out of a magazine. As she stalks into the building, the camera slowly travels down her body from behind. She is a glamorous figure, out of place. The patrons are entranced by her entry, Diana does not notice (or chooses not to notice) the attention and walks up to the counter. She is centred in the frame and Stewart speaks her first intelligible line of dialogue to the camera, almost as if breaking the fourth wall, “Excuse me. I’m looking for somewhere. I’ve absolutely no idea where I am.”

In a better film, the line might be an entry into “Spencer” as an excavation of Diana finding herself. The opening intertitle announces the film as “a fable from a true tragedy.” The word fable feels so right and so wrong. “Spencer” depends on overemphasised abstractions that might announce moralistic fables, but woefully little in its conceptualisation realises any meaning or significance in its intentions. I’ve long thought of Pablo Larraín as one of this century’s most exciting and innovative directors. He’s excellent at excavating the messiness of humanity with an insouciant refusal for simplicity. But for all the technical flourishes in “Spencer” (Johnny Greenwood’s frenetic, amped up score, Mathon’s sleek cinematography, Jacqueline Durran’s glamorous costuming), this film never settles into something that communicates anything nuance. Or anything at all.

Certainly, Knight’s script is the biggest liability here. It sketches a paper-thin idea of Diana and surrounds her with ghostlike figures who retain no significance beyond their conceptual relationship to her: her congenial children, estranged husband, affable chef, or intimidated maid. Everyone here is schematic, including Diana. Larraín’s characters are usually defined by their deft construction: like the mercurial lead in his most recent film “Ema” (a much better version of a mother on the edge of a breakdown); or the ambivalent ad-man in “No”; or the bereaved Jackie Kennedy in “Jackie”, his only other film in English. Those characters are specific and sharp, their films understand them and they tend to retain a careless surety even amidst the worst of the worlds. Here, Diana is the first of Larraín’s leads who feels perpetually lost. This is not a bad thing in itself, but Larraín never finds the right tone with the hollowness of the script and when joined with Stewart’s effortful performance the union is an unhappy one. Even in her moments of privacy, her presentation of this woman it’s too deliberate, too exacting and Knight’s florid language only problematise any sense of something real underneath. There’s an intriguing aspect to Stewart, an American actress whose “Twilight” days have followed her for more than a decade, thrust into this glamorous role. It is so unlike her, and the transformation is part of the pull here. Stewart has been excellent elsewhere and best in “The Clouds of Sils Maria,” where her ability to act out the process of thinking was so well deployed. But Diana in “Spencer” rarely thinks because the script demands no interiority, so her best quality is gone.

That perception of Diana as trapped in her own film might retain some significance if the film did anything with it, but beyond a safari-esque glimpse into a woman suffering and then suffering and then suffering, “Spencer” is indistinct and Stewart is never skilful enough to explicate interiority in the flatness of the script’s characterisation. Her Diana feels like a celebrity trapped in a paparazzi camera’s gaze rather than a woman really revealed to us, or even (especially) to herself. She manages the silences and is best in a moment where she strikes a pose in the film’s most recognisable image (Diana being hounded by paparazzi), but she is felled at every turn when invited to speak. Who is this woman? I couldn’t tell you. And I suspect neither could the players involved. For the first time at the end of a Larraín film, the credits rolled and I was no more edified about any of the characters than when it began. The rest of the cast, trapped playing shadows, fare very badly especially Timothy Spall playing a caricature in the worst of ways.

“Spencer” looks pristine and is shot like a thriller, finding horror in the hallowed halls of royalty but what does it tell us about anything in those halls? Very little.

If “Spencer” is too schematic, one might call “Being the Ricardos” overstuffed. Visually, it is much less ambitious than the splendour of “Spencer,” which is well-mounted, although its aesthetic fails to consistently deepen its themes. But, Aaron Sorkin’s third directorial feature is ambitious in a different way. The primary story, set in 1953 where Ball has a week from hell after concerns about her alleged communism surface, is interrupted by talking heads in the present (writers and producers of “I Love Lucy”) and flashbacks to the early days of Lucille Ball’s romance with her husband Desi Arnaz. The interruptions are unfortunate. The modern talking heads are completely useless. They add nothing of note and leave actors like Linda Lavin, John Rubenstein and Ronny Cox unusually charmless. The pre-1953 interruptions are of a different note. They contain significant ahistorical references the film strangely insists on, it misjudges our need to have the dynamics of Lucy and Desi’s relationship showed to us so slavishly. But it benefits from Nicole Kidman, who is tied to the fate of “Being the Ricardos,” throughout.

Like the incongruity between Diana and Stewart, the incongruity between Kidman and Lucille Ball feels distinct. Ball’s intense comedic registers feel out of sync with Kidman’s more dramatic reputation. The constant referrals to Kidman’s non-comedic skills, and her appearance, have plagued the film since it was announced and it feels impossible not to read this into the film itself which introduces Ball by her voice, saving us from a glimpse of her until the end of the scene. Kidman does not look like Ball, and the cosmetic transformation is inexact. But, even as Kidman’s comedic register is not historically like Ball, her work in the 21st century was defined by a role that feels in-line with what Sorkin asks of her. There’s a scene in “Moulin Rouge!” where Jim Broadbent’s proprietor asks Kidman’s glamorous courtesan how she plans to seduce the Duke, a mark. Kidman moves through a series of potential versions of herself: wilting flower, bright and bubbly, smouldering temptress. The moment lasts half a minute, but it’s part of that film’s engagement with Kidman’s prowess as an actress good at playing acting and an actress good at playing actresses who are always performing. And in “Being the Ricardos”, Lucille Ball by way of Nicole Kidman is always performing.

That the pre-1953 flashbacks work is because Kidman, who never really looks young enough, manages to distinguish the cadence and energy of Ball from decade to decade. Sorkin’s film is conceptually overemphasised. Ball’s communism scare is complemented by her fear that her husband is cheating on her, her jealousy of her colleagues more svelte figure, her unhappiness with the writing team, Desi’s fear of being emasculated on the show, the producers’ worries about Ball’s pregnancy and a handful of other concerns. The film runs just over two hours and still feels like it’s bursting at the seams. Too much is happening. Sorkin has grown more ambitious as a director and that ambition gives way to a clash of visual tones in the film, like a child showing off. If “Spencer” is, at least, aesthetically assured, “Being the Ricardos” feels too agitated. Jon Hutman’s production is doing a lot of groundwork imagining the spaces of the varying timelines, but Sorkin the director is too beguiled with Sorkin the writer to allow the visual team to do the storytelling. Where Knight’s work on “Spencer” is low on characterisation, Sorkin’s script is heavy with it. Each character’s line has a hidden meaning. It’s a busyness which has moments of striking clarity (a conversation between Ball and Nina Arianda’s Vivian Vance, a co-star) but some that feel too worked out (an argument between two writers). But if “Being the Ricardos” is a film doing too much, it has an actress who can thread those variations.

Ten minutes before the film ends, Sorkin gives Ball a private disappointment after what seems like a public win. The moment plays out with Kidman’s Ball and Javier Bardem as Desi in the backstage of a set. Visually, the moment is nothing special, except it’s asking Kidman to sell an emotional wallop that the script shakily offers up. She shouts, she cries and then she interrupts her tears to switch registers to another version of herself within the span of minutes. After a brief talking-head interruption, we return to her now “on” as a different Lucy, equipped with a different voice. Is Kidman ever really Lucille Ball? Maybe not. But what she manages to be, is a range of different versions of a woman threaded together by her eyes, forever darting around the screen taking in everything around her. “Being the Ricardos” never really keeps up with her. Bardem is good, if inconsistent. Arianda is rewarding, but wasted. The rest of the cast ranges from good (Tony Hale) to unspectacular (J.K. Simmons in a role that feels similar to a run of similarly plain-talking men). But it is Kidman who by sheer force of will turns “Being the Ricardos” into something that feels like it’s actually saying something about the rupture between the public and private.

In their way, we might extract some notion of Diana and Lucille Ball as women playing different iterations for those around them, and for themselves. Neither script feels truly clear on presenting this dichotomous relationship between those varying selves, though. But if “Being the Ricardos” feels like a film that understands the woman at its centre, it’s due to the sheer fortitude of Kidman, who recognises that transformation moves beyond the cosmetic. Her work justifies the gambit of this biopic.

Being the Ricardos and Spencer are available for streaming on PrimeVideo or Video on Demand.