By Thomas Harding

Thomas Harding is author of ‘White Debt: The Demerara Uprising and Britain’s Legacy of Slavery’ published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson . You can order the book from One Tree Books in the UK, email sally@onetreebooks.com

Thomas Harding is author of ‘White Debt: The Demerara Uprising and Britain’s Legacy of Slavery’ published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson . You can order the book from One Tree Books in the UK, email sally@onetreebooks.com

You can follow Thomas on Twitter @thomasharding

It was a warm dry day in October when I visited Bachelors Adventure on the East Coast of Demerara. With me, just a few steps from the public road, was the poet and social worker Ras Blackman, who grew up in the village and was kindly giving me a tour.

On 20 August 1823, more than 4,000 enslaved women and men had gathered here, Ras told me, in what had been a cotton field. On the other side of the public road were assembled 200 members of the British militia, each carrying a rifle. I was suddenly overtaken by a sense of awe. Awe at the courage of the enslaved people. Awe at their remarkable organisational skills. Awe at the profound legacy of freedom they had left behind, including for me, a White person.

My journey to Bachelors Adventure had started a year before when I had learned that my mother’s family had made money importing tobacco from plantations in the USA and Cuba worked on by enslaved people. This had come as a surprise. For the past decade, I had written about my father’s family, German Jews who had to flee the Nazis and seek refuge in Britain. My grandmother had been thrown out of university. The family’s house was stolen by the Gestapo. Several relatives were killed in the Holocaust. I have received reparations from the German government. It was not only an official admission of guilt; it was something material. This was part of the process of reconciliation. So if I was willing to identify as a ‘victim’ in my father’s family, to receive reparations from the German government, then surely I had better understand Britain’s role in slavery.

As a child, I had been taught that Britain had been the first nation to abolish slavery, that the effort had been led by the politician William Wilberforce, that we were the ‘good guys’, the great emancipators. I began reading articles and books and was quickly shocked at how little I knew. It soon became clear to me that considerable harm had been done, that a debt was owed. The question then became, who caused this harm and who should bear the cost of restitution?

For a long time, I danced around this question and when I found the answer, it made me a little nervous. I am someone who until recently did not enter ‘White’ on the British census form because it made me feel uncomfortable. I didn’t want the label. It wasn’t the government’s business. But then, after reading about Britain’s role in slavery – which was built on the classification and brutalisation of people according to their skin colour – it became obvious to me that I had to give a name to those primarily responsible: White people.

After all, the vast majority of those who transported the captured Africans to the Caribbean were White. Similarly, the vast majority of those who ‘purchased’ these enslaved men, women and children and made them work on the appalling sugar, cotton and coffee plantations were White. The same is true of the shipowners and sailors, bankers and insurance officers, traders, dock-workers, shopkeepers and countless others who were employed transporting, processing and selling the commodities back in Britain, including my own family. As to the general population who gained from the enormous wealth that poured into Britain on the back of slavery, again the vast majority were White.

To explore this further, I wanted to find an example that captured what British slavery was like in a microcosm. An event that could reveal the complexities of a British slave society in granular detail, the ambiguities involved. A set of characters who reflected different points of view. A colony in the Caribbean was the obvious place to start, the heart of the British plantocracy, one that could shed light on the trade links with the ‘mother country’. Preferably somewhere that could explore whether the abolition of slavery was brought about not just by humanitarians in Britain but also by the enslaved people themselves, through information-gathering, organising, protest and rebellion.

Which is how I learned about the uprising that broke out in Demerara in 1823. In the National Archives in London and Georgetown, as well as online, I found enormous amounts of primary source material about the 1823 uprising. Most importantly, and quite exceptionally, the records included the voices of enslaved women and men, contributing tone and texture to the story. I also spoke to Guyanese historians, including Winston McGowan, Cecila McAlmont, Hazel Woolford, Nigel Westmaas and others. They told me that the 1823 uprising was a critical moment in Guyana’s history and that it had a huge impact on the anti-slavery movement across the British Empire. I was gripped.

From the archives, newspaper articles, memoirs and letters, I learned that the enslaved abolitionists — for that is what they were, they were enslaved and they wished to abolish slavery — were highly organised. At the centre of the uprising, was Jack Gladstone. According to his court testimony, and that of many others, he was the leader (not his father Quamina). It was Jack who gathered intelligence from the dockworkers and the estate managers. It was Jack who confirmed that Governor John Murray was not implementing the King’s instructions to improve the condition of those enslaved. It was Jack who encouraged his friends to spread word of the uprising along the Atlantic Coast. It was also he who said they must keep this plan secret, to be ready for the signal. It was Jack who set the strategy, that the uprising should take place simultaneously across dozens of estates to make it more difficult for the British militia to suppress. And it was Jack who led the abolitionists as they took one plantation and then the next (Quamina stayed at home). Perhaps most astonishingly of all, it was Jack who insisted that the uprising must, if at all possible, be non-violent.

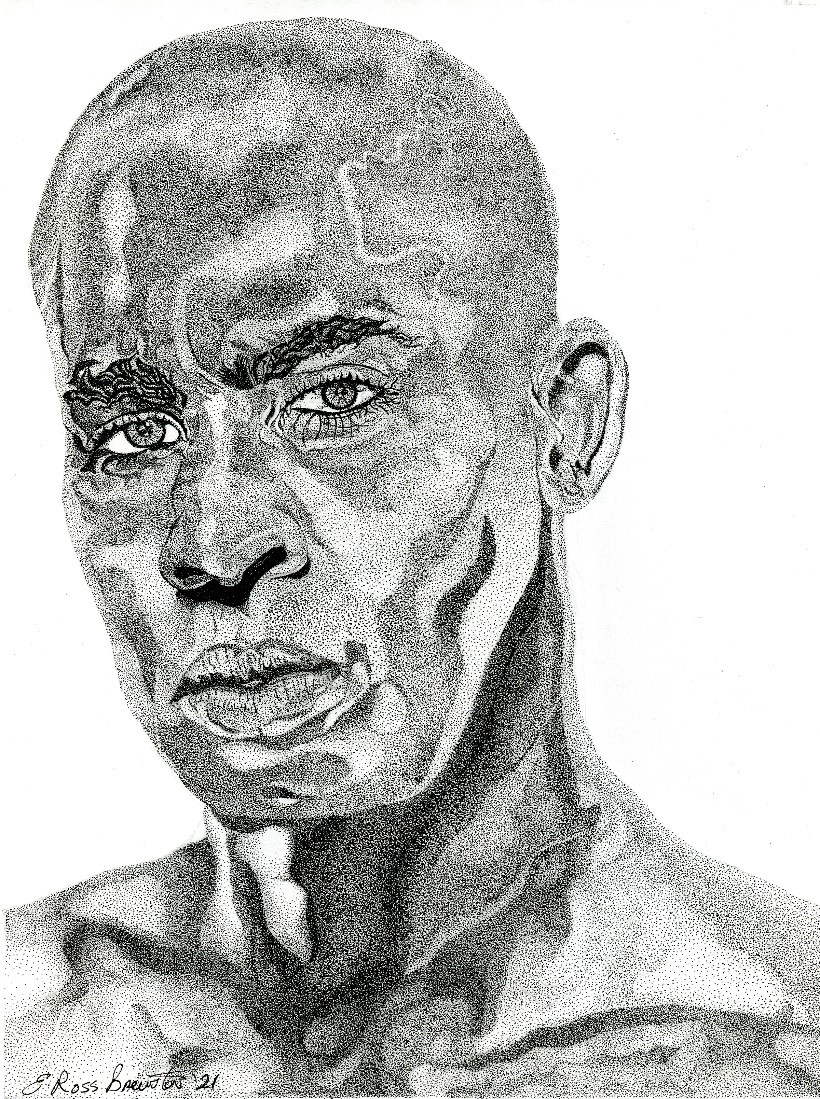

As part of my research, I noticed that there were plenty of pictures of the colonists involved in the uprising (John Smith, John Murray, John Gladstone), but very few of those enslaved. I reached out to Juanita Cox who convenes a diaspora organisation in London called Guyana SPEAKS and we discussed this lack of representation. A few days later, she announced a call for artwork on social media. Shortly after, Juanita put me in contact with Errol Brewster, a Guyanese artist living in Florida, USA. He said that he would be interested in imagining what Jack Gladstone looked like based on the available archival records. He would get to work right away. Several weeks later, the illustration arrived in my inbox. It was stunning. For the first time, I saw Jack: strong, charismatic, handsome, intense. And with that, my connection with Jack and his associates deepened.

Which takes us back to Bachelors Adventure, early in the morning of 20 August 1823. The members of the British militia were now standing fifty yards from the enslaved abolitionists gathered in the cotton field. Upon the command of Colonel Leahey, the order was given to fire. The sound of gunpowder exploding in a hundred rifles filled the air. Scores of men and women collapsed in the cotton field, screaming in pain, clutching at their wounds. Those close by tried to help, holding their fallen comrades, reaching to stop the bleeding.

Meanwhile, the British militia front row reloaded while the men behind stepped forward and fired. Another hundred bullets were let loose. A handful of the freedom fighters fired back, but they had barely any guns and little or no training. In less than fifteen minutes it was over. Hundreds of abolitionists were dead. Those able to escape had fled. Meanwhile, the militia kept loading and shooting, loading and shooting, loading and shooting. It was a bloodbath. More than 200 enslaved men and women were killed. More were injured. Not a single soldier had been hurt, with the exception of a trumpeter who had rendered himself unconscious by drinking too much rum and had been set upon by the abolitionists.

Over the course of the next week, the British militia went from estate to estate, rounding up anyone they suspected of taking part in the uprising. At least another 200 people were briefly questioned before being lined up in front of ditches and shot. In September 1823, a court martial was opened. The jury comprised British militia men who had just taken part in the suppression of the uprising, the trial was overseen by the man in charge of the colony’s slave auction. Many at the time, pointed out that such proceedings could hardly be unbiased. Seventy enslaved people were found guilty of taking part in the uprising, twenty-one of these were executed, most were decapitated, their heads put on pikes as a warning to others. As to the rest of those found guilty, most were severely whipped or confined to chains. What happened to Jack Gladstone? He was sentenced to death, but, after a clemency appeal that stressed his advocacy of non-violence during the uprising, he was deported to St Lucia, where he spent the rest of his life in hard labour.

Ten years after the start of the Demerara uprising, almost to the day, the British parliament passed the Abolition of Slavery Act. I would argue that the Demerara uprising played a big role in the passage of this law. When news of the uprising reached Britain, the population had been shocked by high mortality rates on the plantations and the abhorrent conditions the enslaved people endured. In addition, people in Britain were impressed by the enslaved abolitionists’ careful planning and their efforts to limit violence during the uprising. Jack Gladstone and his associates, had shaken the British establishment into understanding that the enslavement of African people was untenable, since they would continue to fight for their freedom through organised resistance. That they were highly aware and conscious actors, agents of change. That they were human beings with natural rights and the commitment to demand those rights.

To put it simply, the enslaved abolitionists of Demerara — along with those who took part in Sharpe’s rebellion in Jamaica and other insurrections in the Caribbean – played as important a role as the British abolitionists in bringing about the end of slavery.

So what is the White Debt? It is a cultural debt, acknowledging and apologising for the horror that was British slavery. A financial debt, compensating for the economic losses endured by the men, women and children enslaved and the generations of their descendants. And a debt of gratitude, to the freedom fighters of Demerara, who not only won liberty for themselves, through bravery, courage and organisation, but for everyone, all humanity, including White people.