PORT-AU-PRINCE, (Reuters) – The United States is becoming increasingly involved in the investigation of Haitian President Jovenel Moise’s murder, with key suspects facing the prospect of trial in U.S. courts, as a probe by the Caribbean nation’s authorities stalls.

Congress last week ordered the U.S. State Department to produce a report about the July 7 assassination, which deepened a political power vacuum in the Western hemisphere’s poorest country and has emboldened the powerful gangs who serve as de facto authorities in parts of Haiti.

The judge who has been in charge of the case, Garry Orelien, told Reuters in a telephone interview he welcomed U.S. interest in the case as it would help him advance the stalled probe.

“At no time will the involvement of the United States interfere with the investigation in Haiti. On the contrary, it is a plus,” Orelien said. “The United States has the means to apprehend fugitives who are no longer” in Haiti.

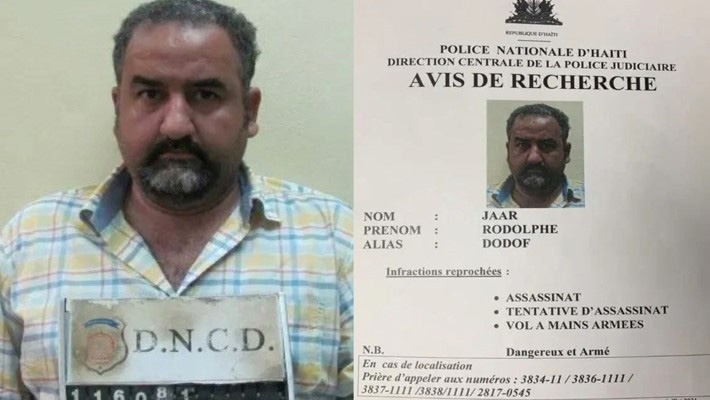

U.S. prosecutors on Thursday charged Rodolphe Jaar, 49, a dual Haitian-Chilean citizen, with conspiring to commit murder or kidnapping outside of the United States and providing material support resulting in death.

Prosecutors in Florida filed similar charges on Jan. 4 against former Colombian military officer Mario Palacios, who Haitian police say was part of a five-man team that stormed Moise’s bedroom and shot him dead. The other four alleged members are in custody in Haiti.

Palacios, first arrested in Jamaica, was brought to the United States in January. Another key suspect arrested in the Dominican Republic was extradited to the United States this week and a third suspect captured in Jamaica could also be handed over to U.S. authorities, according to media.

Palacios stands by his not guilty plea, his lawyer Alfredo Izaguirre said.

Prosecutors in the United States have said one member of the conspiracy, a Haitian-American man they described as “Co-conspirator #1,” traveled to the United States in late June to seek help to further the plot.

Jamaican police on Thursday said former Haitian Senator John Joel Joseph, a suspect arrested last week in Jamaica, will remain in police custody until a court hearing on Feb. 15. It remains unclear whether he will be extradited to either the United States or Haiti.

Haitian police say Joseph supplied weapons and planned meetings for the plot to kill Moise.

The U.S. Congress last Thursday gave the State Department 90 days to produce its own report on the murder, with the help of other agencies. It also ordered an assessment of the independence and capacity of Haitian authorities to investigate the assassination.

In a sign of the disarray surrounding the investigation, Bernard St Vil, head of the Port-au-Prince court system, on Tuesday told Haiti’s Kingdom FM radio that Orelien was no longer in charge of the case because he had not completed it within the time frame established.

Orelien said the delays were not his fault and that he would continue with the case anyway. He said he had been shot at twice and his office broken into during the probe.

A U.S. State Department spokesperson said it supports an independent Haitian investigation and wants those who planned the killing brought to justice.

“Nevertheless, we remain concerned by the slow progress of the investigation and the threats and attacks that have targeted Judge Orelien,” the spokesperson said.

Reuters could not independently confirm the attack on the judge’s office, or whether Orelien had been removed from the case.

Although Haitian police have arrested dozens of people, so far no one has been charged in Haiti. Under Haiti’s legal system, prosecutors file charges after receiving instructions from an investigating judge.

A Haitian police report in August concluded that a little-known Haitian-American doctor Christian Emmanuel Sanon hired a group of former Colombian soldiers to kill the president and seize power. Sanon was arrested in Haiti shortly after the killing. In July Sanon’s brother told the Daily Mail Sanon was not a violent instigator, but did not deny he was in Haiti to seek political change.

Moise’s family says the real masterminds of the attack have not been caught.

“The people behind my father’s assassination are still at large and remain powerful,” Joverlein Moise, the late president’s son, said in an interview, citing the burglary of Orelien’s office as evidence.

WORSENING SECURITY

Moise’s killing further undermined Haiti’s precarious political and security situation, emboldening gangs to expand territory and escalate kidnappings – including the two-month abduction of a group of Canadian and American missionaries.

A group of gangs in October prevented trucks from loading at fuel terminals in an effort to force the resignation of Prime Minister Ariel Henry, leading to weeks of crippling shortages.

Henry has not provided a time frame for general elections, which were originally slated for November but postponed after a devastating earthquake struck southern Haiti in August.

Consulted on the U.S. role in the Moise investigation, a spokesperson for the prime minister’s office said Henry himself had requested international help for the probe.

In a speech to the U.N. General Assembly in September, Henry described Moise’s murder as an international crime: “It is because of this that we formally request mutual legal aid.”

Some politicians are calling for Henry to be investigated for his alleged involvement in Moise’s death, following accusations he spoke with a key suspect, former justice official Joseph Felix Badio, hours after the killing.

Henry, a political moderate named by Moise shortly before the assassination, denies any involvement.

The New York Times last month reported that Moise was compiling a list of officials and businessmen linked to the drug trade before he was assassinated and planned to give the names to the U.S. government. Reuters was unable to confirm this.

Complaints of intimidation of officials have dogged Haiti’s investigation. Weeks after the murder, court clerks Marcelin Valentin and Waky Philostene said they received phone calls threatening them if they did not alter records or remove certain names from registries, according to letters seen by Reuters.

Some Haitians say the involvement of the United States in such a high profile crime signals an alarming deterioration of the country’s justice system.

“What is happening clearly shows how impunity is growing,” said Pierre Esperance, of the National Human Rights Defense Network, adding that the police and judicial authorities have not done enough to advance the investigation.

“Haiti cannot have rule of law without good governance.”