By Errol Ross Brewster

Errol Ross Brewster is a Caribbean artist from Guyana, who has lived in Barbados, and is currently living in the United States. He was educated at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, Canada, and served as Director of Studies at the E. R. Burrowes School of Art in Guyana. With more than four decades of a Caribbean-wide, multimedia imaging practice, he has participated in multiple CARIFESTA’s; the EU’s Centro Cultural Cariforo, “Between the Lines”, travelling exhibition, 2000; the First International Triennial of Caribbean Art, 2010; and the Inter-American Development Bank’s “Sidewalks of the Americas” installation, 2018. You can read more about him and the influences on his artistic practice online in his conversation carried on Veerle Poupeye’s blog about art in the Caribbean and beyond.

Errol Ross Brewster is a Caribbean artist from Guyana, who has lived in Barbados, and is currently living in the United States. He was educated at the Ontario College of Art in Toronto, Canada, and served as Director of Studies at the E. R. Burrowes School of Art in Guyana. With more than four decades of a Caribbean-wide, multimedia imaging practice, he has participated in multiple CARIFESTA’s; the EU’s Centro Cultural Cariforo, “Between the Lines”, travelling exhibition, 2000; the First International Triennial of Caribbean Art, 2010; and the Inter-American Development Bank’s “Sidewalks of the Americas” installation, 2018. You can read more about him and the influences on his artistic practice online in his conversation carried on Veerle Poupeye’s blog about art in the Caribbean and beyond.

Being a frequent visitor to the Guyana SPEAKS Facebook page, I saw posted there a call for artwork for the British writer Thomas Harding’s book on the 1823 Demerara Revolt, ‘White Debt: The Demerara Uprising and Britain’s Legacy of Slavery’, which has just been published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson. As a text about a history I was familiar with, I was immediately interested. Much of my work is inspired by history, so this was right up my alley. The idea of doing imagined portraits of historical characters for publication in an historical text was something to hotly pursue, especially as one of the desired portraits was of an obscure woman leader, Amba. I dove into the book written by the Brazilian historian Emilia Viotti da Costa, ‘Crowns of Glory Tears of Blood: The Demerara Slave Rebellion,’ which was recommended to me by Dr. Juanita Cox-Westmaas, of Ghanaian/British heritage and a naturalised Guyanese citizen, who with Rod Westmaas co-ordinates Guyana Speaks, an initiative that was set up in 2017 and that hosts monthly gatherings on a topic pertaining to Guyana.

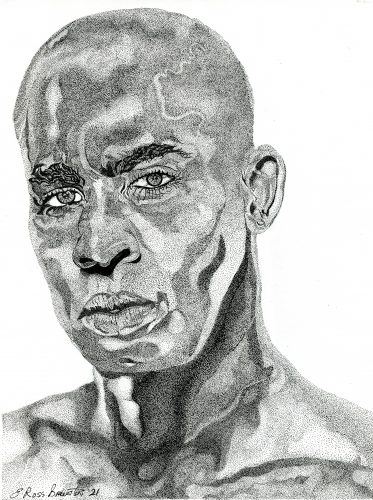

From the details in da Costa’s book, I conjured up Amba and Jack Gladstone, two of the leaders of the 1823 rebellion. Portraiture arises out of good eye/hand coordination. By that I mean that what is required is accurate recording of keen observation of the subject. Descriptions of Jack Gladstone appearing in a Wanted advertisement in a local newspaper in 1823 offering one thousand Guilders for his capture alive. It stated that he was about “twenty-five years of age; handsome, well made; rather a European nose; good white teeth” Other descriptions of him were revealed in da Costa’s book, which provided wide-ranging details of the man’s character and personality through its reports of his interactions with a cross-section of society, from the Governor’s personal servants to fugitives from other plantations hiding in broad daylight. The most useful description of Jack Gladstone’s physicality for me was that he was 6 feet, 2 inches tall. This information was also provided in the Wanted advertisement. People are proportioned, roughly, at one to six. His head would, therefore, have to be about twelve inches if his whole body was seventy-four inches.

Everything else was about what kind of man Jack Gladstone was. It’s not a keen observation kind of business this. It’s a reverse engineering job! I would have to understand who he is and translate that to what physical characteristics people associate such qualities with. Folks tend to know who’s a scamp and who’s bright as a lamp from their physical appearance. This is quite commonplace. So, who was this son of an enslaved Ghanaian man of God – the Christian God? The archives reveal that his father, who had the Akan name Quamina, was a deacon in Rev. Smith’s church, a man of influence in the community, respected and trusted by his congregations, including some Whites. His son Jack, with whom he was close, was associated with the church but not an adherent (I made a mental note to self – he’s of his own mind).

We learn, also, that the Prosecutor in the Kangaroo court case found Jack to be an extraordinary man. The Governor also recognized that his motives were purely political, and this would have an impact on the outcome of the case too – banishment to St. Lucia with hard labour instead of death. These are no ordinary set of circumstances he was engaged in. They would necessitate a highly contemplative man to navigate, I think. And this had big implications for the drawing. It meant Jack Gladstone must have had tremendous presence, an engaging aura. Da Costa’s text also revealed that Europeans, who in their low regard of Africans ordinarily reduced them to ‘other’/ invisibility, found him to be of a striking appearance.

As a skilled artisan, Jack had a certain freedom. He would be hired out to neighbouring plantations. The text reveals him as a man who wielded influence among men and women. He was said to throw himself into all his undertakings with full heart and hand. As an artist, I had to translate this into features in my mind’s eye – strength of character, bold decisiveness, daring, intensity, questioning concentration – they gave good direction to the hundred and one dots scattered across the page to bring Jack Gladstone to life. The text’s telling of a range of interactions with others confirmed these qualities that gave all great confidence in his leadership. These got translated to a furrowed brow, square set jaw line, determined chin (dimpled for good measure) a penetrating gaze from out sensitive eyes, and lips, fulsome with probing question.

The level of clandestine organization and coordination, along miles of coast and over weeks of planning, spoke to a clever mind and a high determination. These necessitated the domed forehead of an ample crown, tilted in anticipation of weighing what response the enquiry on his lips would bring to his ear. Their cross-referencing convincing Jack that all the rumors, that the planters were hiding the news of emancipation, were true. This filled him with an impatience for his longed-for freedom to be his own man. And da Costa’s text reveals the surprising fact of his wish to avoid violence. His actions saved some Whites from certain death, including the very man who arrested and detained him. Such was his ennobled intent and the extent of his influence in steering others to that goal that the governor, recognizing it, pleaded for leniency. He feared that execution – the court’s verdict on Jack – would mean that Regent Street might bun dung.

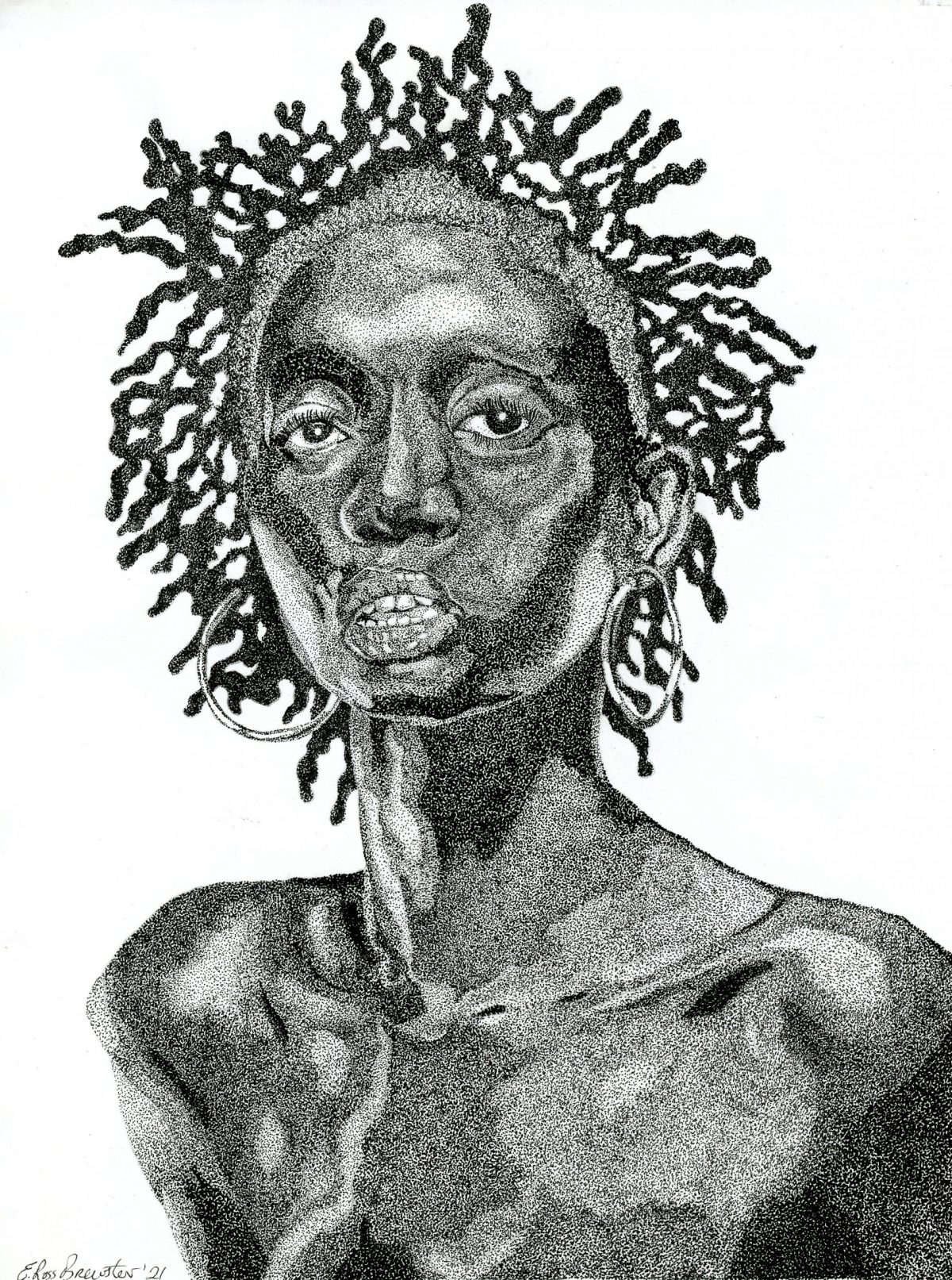

Amba, a leader in the revolt, was a young woman exhibiting deep anguish, calm but determined, with an implacable intent to revenge her people, with no compunction. She has come to appear to me as an artist as she does by the same reverse engineering I employed with Jack. The text revealed that she led the freedom fighters on that fateful morning in August 1823, marching them miles to the overseer’s house, where they stood in the cold dark foreday morning, to await his emergence into the hostility of her intent.

Amba was a woman apart, exercising an outsized influence over others of the enslaved on the plantation she laboured at. Like most African women her age she was likely possessed of a lissome figure. She was said to be tall, wiry, with narrow shoulders. I imagined her to be a gawky woman whose influence over other came not so much from her physicality. She was like a broomstick, but strong. The force of her command came from her determination. Seeming to be all seeing she would look people over with her big baleful eyes which signaled that she did not tolerate frivolity. The men she commanded well knew this. Her locks, which she did not cover as did other women, stood prominently on her head, seeming to mirror the fighting men standing in a seething silence that morning outside the overseer’s house.

Who among the enslaved women wore jewelry? No one, but in my mind’s eye Amba fashioned hoop earrings for herself, and I imaged her as having the extraordinary presence of a runway model. One modeling such fierce intent that she was aghast that her men were having difficulty disarming the overseer; according to the declaration of one Mr. Shepard, of Porters Hope, in the court transcripts, she ordered that they shoot the overseer. What, just the day before, the overseer would have seen as insubordination on Amba’s ready lips, he would now have understood as being her strong self-assertion. On this particular morning, suited in his well pressed, short khaki pants, her demeanor held a frightening control over him. And in that moment, he could tell that by her nose she understood the fear he was feeling. She signaled the men to drag him off to the plantation stocks. These leaders could make such choices, because of their confidence in the justice of their cause. It gave them a steely, laser focused determination, a sure knowing of their purpose – the commendable attributes of great leadership. Not hatred, not anger, astonishingly. Look them in their face; you’ll see that humanity! This is what I tried to communicate in the two portraits I produced.

Having an equal part of my heritage (according to DNA test results) tied to the tumultuous horror of enslavement, and being a descendant of those of the Fante people ripped from their homeland, family, name, traditions, and language, I feel an urgent imperative to help gather the scattered fragments of history through my art. This request of Thomas Harding, the author of the just published White Debt, for portraits of the leaders of the 1823 Demerara Revolt, played directly into that aspiration of mine, and I thank him sincerely for the opportunity to contribute to the book. I hope to parlay this visualizing of these two important historical figures into the commissioning of local artists by the Guyana government and the private sector to involve our young people in the creation of a series of large fresco murals of the significant leaders of our historical resistance efforts and to also embed them in our currency. This way people may have them at hand to bring to bear on us, in a directly felt manner, our awesome responsibility to be free of domination local or foreign. A celebration of the1823 Revolt with a two-hundred-dollar coin in 2023! And as a fitting tribute to our ancestors, let us rename Middle Street, along which the decapitated heads of freedom fighters were placed on stakes to dissuade further attempts to be free, to Avenue of the !823 Demerara Revolt, tuh please!