In writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson’s latest feature, “Licorice Pizza”, a warm and fuzzy preoccupation with the past overwhelms the languorous manoeuvrings of its 134-minute running-time. One might call that preoccupation “love”, but the word seems incongruous with the tone of the film itself; it is too intentional and specific for the complacent mood of the film even as overtures (or pretensions?) of love feel central to the sliver of plot that keeps it afloat. At every moment “Licorice Pizza” reminds you, with a shrug or a careless defiance for any sense of context or meaning, that it is not a film about being deliberate. Instead, it invites us to observe a series of individual moments that might be connected as we traipse the 1970s in the San Fernando Valley of Los Angeles.

At the centre of the lark is Gary, a fifteen-year-old child actor. Gary is ageing quickly out of cherubic teen-years, but is unfazed by this potential predicament. In fact, nothing seems to faze Gary, a teenaged huckster with enough time and money to glide from one business venture to the next. He’s almost unbearably full of himself but the egoism feels apropos. The world available to him allows Gary to ease through life uninhibited by anything, so that when he meets a woman ten-years his senior, Alana, who seems to be experiencing actual malaise in a dull job taking high-school photos, Gary is intrigued by her. She is needled but reluctantly charmed by the tenacity of this teenager whose confidence belies his age, and so over the course of a few months or more (the film is cleverly indistinct about the passage of time) we follow their ambivalent romance throughout San Fernando Valley.

This set-up could go a number of ways, and Anderson’s works have often been interested in carving narrative context from fragmented worlds and lives – all the way from “Boogie Nights” up to his recent “Inherent Vice”, the last of which is most temporally and sometimes tonally similar to “Licorice Pizza”. There’s clearly an element of care put into this, the period meant to evoke Anderson’s childhood existence – so the film feels framed by that kind of focussed commitment to evoking a time and place. But the breezy and evocative confidence of the opening sections very soon give way to a casualness that I found increasingly listless. From its set-up, Anderson (who wrote the script and also serves as co-cinematographer) insists on binding Alana and Gary together, but their bond feels nebulous; they are connected more because of narrative conceits than an any genuine internal logic that deepens over the course of the film to contextualise the attraction, romantic or otherwise.

Of course, this refusal to contextualise anything is intentional; “Licorice Pizza” is emphasising a version of LA hangout culture – the noble art of “vibing” one’s way through life. And either it works for you, or it doesn’t. It doesn’t work for me. Anderson does establish the aesthetic of this world with clever immediacy, he and co-cinematographer Michael Bauman are imitating a particular kind of visual cadence that recalls Gordon Willis’s visual nonchalance from that era. The images often feel indistinct, and natural in a way that fits into what actual films of that period looked, or felt like. It’s that distinct visual tone that affirms the likelihood that this kind of unstudied vibe is exactly Anderson’s intentions, but beyond the look of it – the lived-in costumes from Mark Bridges or the cluttered and neurotic production design from Florencia Martin (evoking some lovingly ugly interior designs) “Licorice Pizza” feels nonchalant to the point of empty.

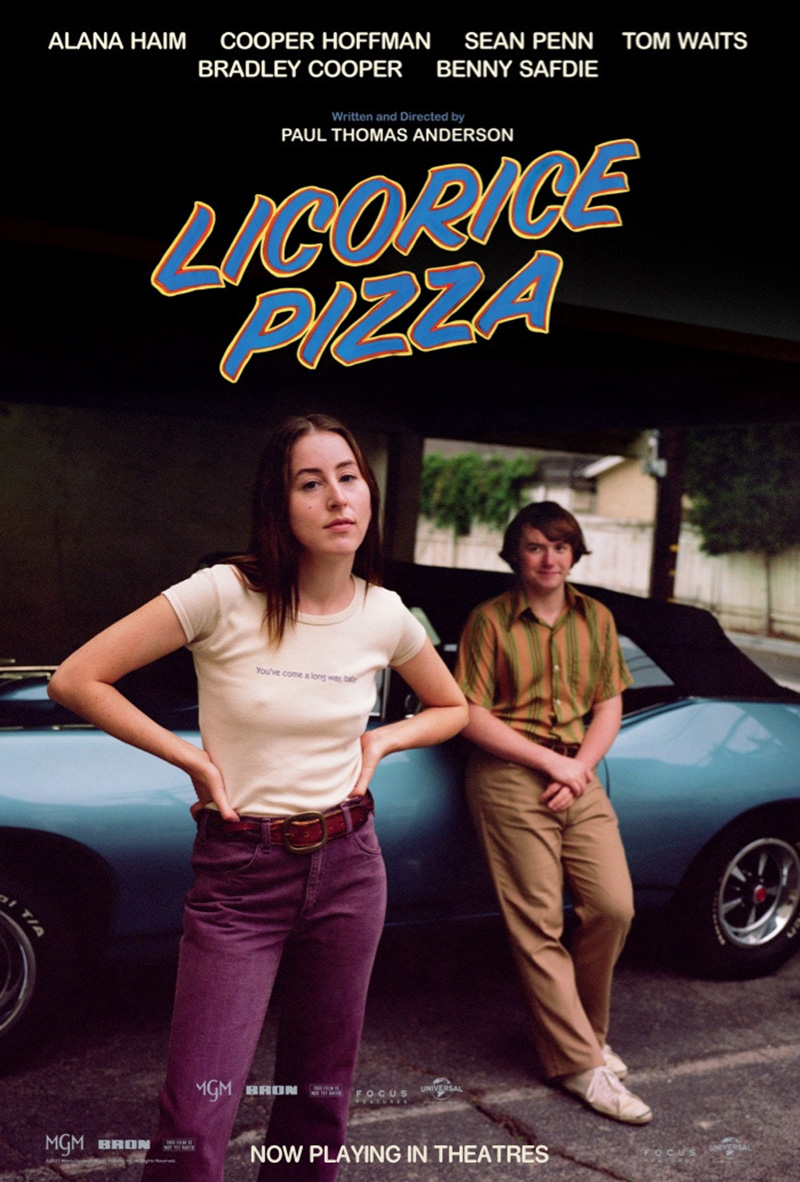

Gary and Alana are played by newcomers who are linked to Anderson in real-life. Gary is played by Cooper Hoffman, the son of the late Philip Seymour Hoffman (an inimitable talent and a long-time Anderson collaborator) and Alana is played by Alana Haim, of the Haim sisters, who Anderson has known for some decades. Neither has much experience with acting and neither ever truly works amidst a film that allows all its notable performers to appear for brief scenes as Alana and Gary rollick through the valley. Gary’s one-note characterisation is a gratingly unctuous smile, and Alana’s is a wince. Haim, who is better than Hoffman, works to pull some kind of internal characterisation from the plot but there’s little to work with, and a novice performer is not what the narrative listlessness of this film needs to hang itself on.

For all the care put into the very precisely curated vision of languor, I am doubtful that there’s any real interest in what these characters are thinking beyond what they say or beyond what the plot necessitates. The internal logic of the material feels tepid and that Haim is left to carry the brunt of an emotional turn in the film’s last third feels unfair to her and the film. That final third depends on her character recognising something about her relationship with Gary. But it’s not just that it’s hard to see what she thinks about him beyond some moments of compulsion it’s hard to discern what Alana thinks about most anything here. It is similarly hard to understand or even recognise what Gary actually likes about Alana beyond the allure and his teenage lust and compulsion to insist on getting what he wants. The string of extended celebrity cameos reminds us of the seediness of the world, with a series of performances that are intriguing if not particularly indelible, but contextualising the central “romance” against them feels hazy. What’s the dramatic shift between Alana and Gary in their first scene as compared with their last? Nothing really. Except beyond what the film deigns to find in an ending that feels like it’s supposed to wash over us like a dream, but only worked as a calcification of all that I found frustrating hitherto.

Those on its wavelength might be sensitive to the criticism wielded against the film, its immorality or its racism and the query of the need for us to like characters. John Michael Higgins turns up twice for an extended joke about a Japanese accent that adds nothing to the proceedings. More complicated is the film’s own ambivalence to the age-gap between Gary and Alana, which has caused ire in some circles. The film is ambivalent about commenting on it, and it never registers as a matter of import for me mostly because the film itself feels so listless but it is intriguing reading the final frames of the film in context of the gap and wondering what exactly that coda is meant to evoke. I don’t care about any of these people enough to worry. I don’t particularly like any of the characters in “Licorice Pizza”, sure. But it’s hardly the thing about it that indicts it. Anderson’s “Phantom Thread”, which is very likely my favourite film of his, features a trio of characters, each more exhausting than the other. But they are fascinating to watch, both because of what they do and how they do. In “Licorice Pizza”, that doesn’t translate. Occasionally, a moment interrupts the languor – Sean Penn is compellingly inconsistent as an ageing actor, Harriet Sansom Harris is enthralling as a hawk-like press-agent, Benny Safdie plays perhaps a rare figure of warmth, in an arc that almost comprises all of that warmth. But no matter the interest stirred by the occasionally well-established cameo, “Licorice Pizza” is deliberately averse to investing real interest in them. Instead, we return to Alana and Gary who consistently seem so much less compelling than the world they exist in. Who are these people? Why do they matter? Either you are with it, or you’re not. And I never found myself truly with it in this. Whatever “it” is.

By the end I was more exhausted than enchanted or intrigued or even illuminated. Within the ambling restlessness of the “no-thoughts-just-vibes” energy of it all, it’s hard to connect how the increasingly careless fragments are meant to be working towards the neon-lit final scene, where a reunion feels like a would-be rapturous event. One might explain away the directionless as a part of Anderson’s own creative framework, remembering his past, it’s curious to measure this against Quentin Tarantino’s “Once Upon A Time…in Hollywood”. Like Anderson, Tarantino devoted his ninth film to traipsing through the era of his childhood but there the nonchalance felt purposeful and challenging. Here, it’s all too hazy to register. You can, maybe, connect the dots if you squint, but I never believed in any of these people or this world, for all the aesthetic surety of its approach. Anderson’s visual specificity is too precise for the film to be unsalvageable but I was disengaged for most of “Licorice Pizza” – formless, and casual and just there. Sure, it’s a film that’s all about the magic of feeling the vibes. But the vibes don’t work if you don’t believe in the magic. And I never believed in any of this.

Licorice Pizza is currently playing at Caribbean Cinemas