Embassy

As evening fell the day’s oppression lifted

Far peaks came into focus it had rained

Across wide lawns and cultured flowers drifted

The conversation of the highly trained

Two gardeners watched them pass and priced their

shoes

A chauffeur waited reading in the drive

For them to finish their exchange of views.

It seemed a picture of the private life.

Far off, no matter what good they intended

The armies waited for a verbal error

With all the instruments for causing pain

And on the issue of their charm depended

A land laid waste, its towns in terror

And all its young men slain.

– WH Auden

The Shield of Achilles

She looked over his shoulder

For vines and olive trees,

Marble well-governed cities

And ships upon untamed seas,

But there on the shining metal

His hands had put instead

An artificial wilderness

And a sky like lead.

A plain without a feature, bare and brown,

No blade of grass, no sign of neighbourhood,

Nothing to eat and nowhere to sit down,

Yet, congregated on its blankness, stood

An unintelligible multitude,

A million eyes, a million boots in line,

Without expression, waiting for a sign.

Out of the air a voice without a face

Proved by statistics that some cause was just

In tones as dry and level as the place:

No one was cheered and nothing was discussed;

Column by column in a cloud of dust

They marched away enduring a belief

Whose logic brought them, somewhere else, to grief.

She looked over his shoulder

For ritual pieties,

White flower-garlanded heifers,

Libation and sacrifice,

But there on the shining metal

Where the altar should have been,

She saw by his flickering forge-light

Quite another scene.

Barbed wire enclosed an arbitrary spot

Where bored officials lounged (one cracked a joke)

And sentries sweated for the day was hot:

A crowd of ordinary decent folk

Watched from without and neither moved nor spoke

As three pale figures were led forth and bound

To three posts driven upright in the ground.

The mass and majesty of this world, all

That carries weight and always weighs the same

Lay in the hands of others; they were small

And could not hope for help and no help came:

What their foes like to do was done, their shame

Was all the worst could wish; they lost their pride

And died as men before their bodies died.

She looked over his shoulder

For athletes at their games,

Men and women in a dance

Moving their sweet limbs

Quick, quick, to music,

But there on the shining shield

His hands had set no dancing-floor

But a weed-choked field.

A ragged urchin, aimless and alone,

Loitered about that vacancy; a bird

Flew up to safety from his well-aimed stone:

That girls are raped, that two boys knife a third,

Were axioms to him, who’d never heard

Of any world where promises were kept,

Or one could weep because another wept.

The thin-lipped armourer,

Hephaestos, hobbled away,

Thetis of the shining breasts

Cried out in dismay

At what the god had wrought

To please her son, the strong

Iron-hearted man-slaying Achilles

Who would not live long.

– WH Auden

The Hand That Signed The Paper

The hand that signed the paper felled a city;

Five sovereign fingers taxed the breath,

Doubled the globe of dead and halved a country;

These five kings did a king to death.

The mighty hand leads to a sloping shoulder,

The finger joints are cramped with chalk;

A goose’s quill has put an end to murder

That put an end to talk.

The hand that signed the treaty bred a fever,

And famine grew, and locusts came;

Great is the hand that holds dominion over

Man by a scribbled name.

The five kings count the dead but do not soften

The crusted wound nor pat the brow;

A hand rules pity as a hand rules heaven;

Hands have no tears to flow.

– Dylan Thomas

This is the poetry of war. Not that war is poetry, since it is antithetic to the humanitarian and the aesthetic, as the poems reproduced here demonstrate. But, throughout history, poetry has been closely associated with war.

In modern thought, it is difficult to see the poetic in a war as it can be imagined in sports and many forms of human endeavour or achievement. Beautiful wars do not exist, and these poems attest to that. However, as one will find in the history of poetry, verse has had an association with war as old as poetry itself.

This is not confined to western poetry, as the same may be seen in traditional verse, oral poetry, in Africa, for instance, or in the ancient scribal traditions of Chinese poetry. The great epic poems of Homer count war as glory and as heroic – at the very heights of national honour. Moving down the centuries, poetry related to war and heroism was the essence that sustained the human spirit, kept hope among a people accustomed to constant war in the Middle Ages. Chivalry was a philosophy born out of horsemanship and honour in battle. War poetry accounted for a considerable share of world literature.

Today we live in more enlightened times when words, diplomacy, reason, humanitarianism will prevail in any conflict. Or so we thought, until Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine in late February, this year. The response of NATO and the allied west seems restricted and restrained because they are conscious of the real possibility of a world war – an outcome that they are trying to avoid. There are many spinoff terrors and hardships for ordinary people around the world even as a result of the carefully downplayed measures taken by various governments to sanction and pressure Russia.

Many of these have economic effects which are already being felt way outside of Russia and Europe. Oil and international banking are much affected, and not even Guyana’s new oil is making it immune to the repercussions. The common man will feel it in the rise of prices for even basic consumer items. The poems reveal the cruel and widespread hardships that are felt by people, the genocide and devastation, cities and lands laid waste by acts of war, insurrections and totalitarianism.

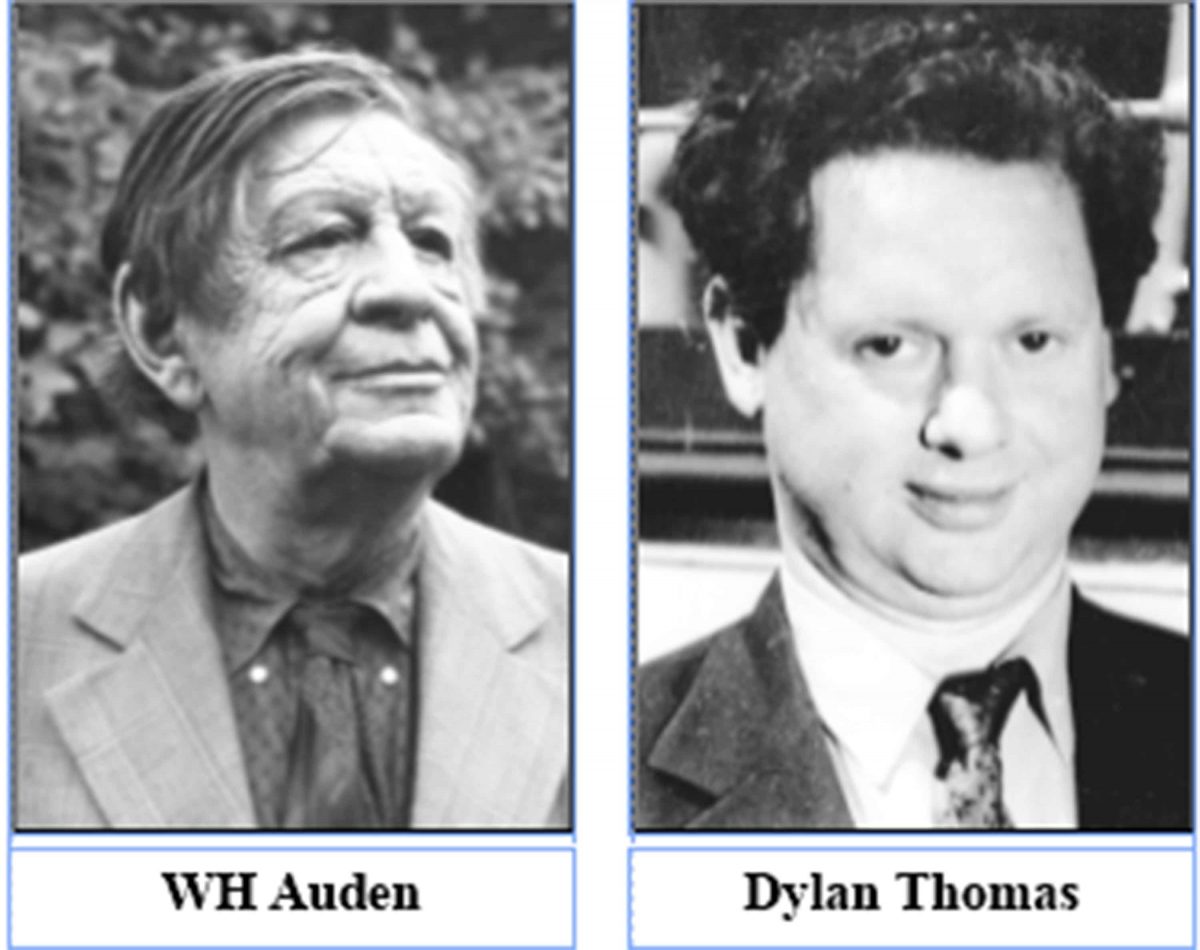

The poem “Embassy” by WH (Wystan Hugh) Auden (1907 – 1973) has other titles. It is also called “The Embassy” and “Sonnet From China” and was written in 1936 – 1940 as a part of a sonnet sequence when Auden and his companion Christopher Isherwood made an extended visit to China as travel writers. Auden, a British-American poet of a socialist, perhaps Marxist persuasion, focused on war, as he closely observed the invasion of China by Japan at that time. He ironically set the poem in the well-cultured, wealthy, middle-class suburb where the embassy was located and put it in stark contrast with the working class, the soldiers and the terrifying mass destruction and havoc wreaked by war.

Auden’s other poem, “The Shield Of Achilles” was published in 1955. Again, it exposes a contrast between the idealism of war on the one hand and the harsh, tragic dislocation, human violation, reduction and plunder it wreaks on the other. The poem goes back to the classics, to Greek mythology and the story of the great, indestructible hero Achilles, famous for victory in the Trojan War. Achilles’ mother looks over the armourer’s shoulder as he makes a new shield for her warrior son. She expects to see the glories of Greece etched in pictures on the shield, but instead, the wise, far-seeing armourer carves images and pictures of slaughter and waste, which are the realities of the wars that Achilles will use the shield to wage. It is as if the bright, shining shield is reflecting the future.

“The Hand That Signed The Paper” is by another of the great visionary poets of the twentieth century, Dylan Thomas (1914 – 1953). Like Auden, he observed the slow, steady rise of totalitarianism around Europe and the two World Wars. This poem focuses on the great and widespread mayhem, waste of lands and nations and the annihilation of human life that can result from a single signature on a piece of paper. It opposes dictatorship and the absolute power a totalitarian ruler has in his command over humanity. The world of dead can double and a country cut in half on his say-so.

Poetry can be a powerful force against war, dictatorship and interterritorial aggression. The twentieth century witnessed the outstanding work of Seigfreid Sassoon and Wilfred Owen, who were voices against World War I. But even at a time when epic poems glorified war there were poetic voices against it. Testimony to this is the comedy drama Lysistrata by one of the great Greek playwrights of the fifth century BC, Aristophanes.

Today, as the world thought it might be slowly moving out of the oppression wrought by the COVID-19 pandemic, it is faced with the prospect of continuation of hardships because of the military aggression against Ukraine.

A good example of the effects of World War II on the lives of people far away from the actual war zone is Caribbean poet Louise Bennett’s satirical “Dutty Tough”. It draws from the Jamaican proverb, “Rain a fall but dutty tough”, to show the deterioration of not only the economic means of West Indians in wartime, but the ill effects on interpersonal relationships. Today sports, travel, trade and a range of other things are either throttled or under threat.