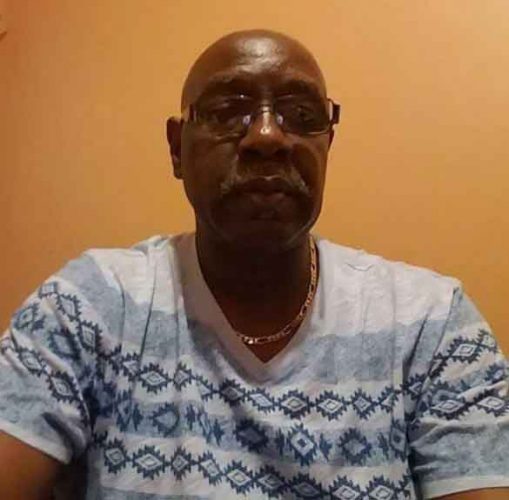

On the death of her husband Clarence Young in October 2017, Co-founder and Chief Executive Officer of Phoenix Recovery Project Inc, Samantha Prince-Young vowed to keep the facility open and almost five years later she is satisfied that the organisation is continuing to help people to reclaim control of their lives from addiction due to substance abuse.

“I am satisfied we have made positive changes in people’s lives and from among young and brilliant people who are caught up in addiction. When I see them back in work places and doing their little businesses it makes one feel good. Not everyone who come into rehab will be 100 per cent successful but we are grateful we have steadily seen successes from those coming in for treatment,” Prince-Young told Stabroek Weekend, while revealing that over 150 persons have been helped since her husband’s passing.

As Young’s family continues to keep his legacy alive, Prince-Young said, it could not have been possible without the support of the staff and the board of Phoenix, and other stakeholders, including the government of Guyana which provides an annual subvention.

“We put the subvention and fees charged for treatment from those who could afford together to balance our budget.”

The last of 12 children, Prince-Young’s first encountered addiction through her father, who was an alcoholic and then three of her siblings who were alcoholics and who were also hooked on harder substances.

In spite of her father’s addiction, she had a strong Christian upbringing as a member of the Seventh Day Adventist Church, where she recognised early in life she needed to get more involved in helping people than just going to school or going to church. She did not know how that was going to evolve. However, involvement in youth work and ministry through her church kept her in line.

A past student of St Joseph High, she is today an accountant by profession. She worked at a few places before starting her career at Marian Academy in 1998 shortly after the school opened its doors for the first time.

She was born and raised at Public Road, Kitty to a Trinidadian father and a Guyanese housewife.

Even though Clarence Young visited Guyana regularly between 1993 and 1994 and had begun to reside in Guyana prior to their meeting, the two met in Trinidad while Prince-Young was doing an advanced Association of Chartered Certified Accountants course at UWI, St Augustine Cam-pus. They subsequently married in 2000.

“Clarence was the person who brought the leading treatment for addiction to Guyana. Nothing was in place for treating addiction prior to him coming here. Families who could have afforded it took their loved ones to Trinidad and other Caribbean countries or further afield for treatment for substance misuse disorder.”

Young was himself an addict of crack cocaine. “He had many years of struggles on the streets of Port of Spain. After a successful period in rehabilitation he started to support the facility that helped him. It is a common belief that in helping others you help yourself.”

In giving back, Prince-Young said, her husband was encouraged to come to Guyana to set up a facility to help Guyanese but he was discouraged by his Trinidadian friends who told him Guyana was a hard place. “They used a simple loaf of bread for G$100 to try to deter him but did not succeed. He worked tirelessly in various bodies and groups, setting up the necessary policies on drugs and in any area he could have dealt with. He made Guyana his home. When he went to programmes in Trinidad to represent Guyana I would tease him when he said he couldn’t wait to get back home. I would tell him ‘but you’re home’. I’m happy he took up the challenge to come to Guyana because over the years based on the numbers of persons who came through Phoenix their lives have been reformed.”

Young was first invited by families whose loved ones were receiving treatment at facilities where he offered his services in Trinidad.

“Some of those very relatives and associates provided accommodation for him initially. Unfortunately, most of those people would have passed on.”

His first out-patient programme was at Prashad’s Hospital. After that he was approached to do a men’s programme by the Salva-tion Army. He designed and implemented the Salvation Army Men’s Programme in 1996.”

The rise of the Phoenix

After Prince-Young and Young were married in 2000, some internal changes at the Salvation Army led to Young being unemployed. “He was becoming frustrated with not much to do. One day at work I thought I could encourage him to do something at home that could make him feel a sense of purpose. We discussed it and I approached the then landlord where we were renting in Hadfield Street. She said if I was comfortable with him starting his own rehab programme, she had no problems. It was a decision I took. It meant our family had to share space with people who were not family.”

When they started the programme in Hadfield Street, Prince-Young said, “We did not know whether we would have done it for one year, two years or three years. Today Phoenix is over 20 years old. When we started we had no name for the facility.”

The name Phoenix was taken from the depiction of a painting that Young had done on completion of his rehabilitation. His depiction was an intention to run his own programme. He did not bring the painting to Guyana because he had forgotten about it.

Prince-Young related that one August during a visit to Trinidad she was helping her mother-in-law to clean up. There was a box with some things to throw away. Curious about what was in the box, she opened it and found among the items a painting. “It caught my attention because it was a painting of a phoenix. Knowing the symbolism of the phoenix, I asked Clarence’s mom whose painting it was. She said it was his. I brought it to Guyana and gave it to him, reminding him of his intention.”

Young started Phoenix in October 2000 but it was not registered as a non-governmental organisation until 2007.

Eventually there was need for expansion. The family and Phoenix then moved to Sparendaam, where they accommodated 12 men. The Hadfield Street home accommodated four men. Clients come through referrals from those who were rehabilitated.

In 2008, the women’s programme came about. Initially, Young was hesitant to run a women’s programme.

“I encouraged him to do the women’s programme because I had a sister, now deceased, who was a drug addict. She needed help.” The start-up of the women’s arm of the project was funded by the US State Department through the then Catholic Relief Services (CRS) in Georgetown. Today the facilities for both men and women are located in Mon Repos and run by a staff of ten, including Prince-Young and three counsellors. One of the Young’s children assists in counselling and the other in administration. Both children, Jahleel and Jahrier, are at the University of Guyana.

“The good thing about it is that both of my children lend support in a full time capacity. They have virtually grown up in the programme. One is into administrative and the other in counselling. It is a legacy that the family is literally carrying on. People are surprised to see young people involved.”

In 2019 through the Caribbean Community Secretariat most of the staff took part in courses on substance misuse disorders at the University of the West Indies, Mona Campus. In relation to training and keeping abreast of new protocols and international practices, the staff have also been taking part in webinars sponsored by the Inter American Drug Abuse Control Commission (CICAD) of the Organization of American States.

“Whenever government ministries or agencies like the Customs Anti-Narcotic Unit have training programmes they also include us.”

Phoenix caters for 40 men and ten women. However, occupancy is averaged between 25 and 35.

Most people admitted to the facility are for using more than one substance.

“We call them poly users. They use more than one substance at a time. Someone’s primary substance may be crack cocaine but they use alcohol. Another’s primary substance may be alcohol but they use marijuana. Today you rarely find someone coming in for one primary substance. Once it is not a case of induced psychosis the process of treatment becomes a lot easier. When they are detoxed they are not on any chemical treatment thereafter. That process is easier than for someone caught with psychosis induced issues. We do not deal with the psychosis or mental issues part. That is a condition that may require medication.”

While women are more hesitant to seek help, Prince-Young said, “In every 15 men we get about one woman. It is easier to get men to accept that they need help, but women are a little hesitant. However, with women, their serenity period is longer and their success rate is higher than men.”

Three phases

The programme is strictly residential and is run in three phases. The first phase focuses on detoxification, that lasts from six to 12 months. In the second phase there is a half way home that allows the client to work and earn a living. The programme is basically the same for both men and women.

“If after six months the family is not satisfied or the client is not successful in rehabilitation, the client may continue on the 12 month programme. Because of Covid-19, families asked for the 12-month programme.

The second phase involves a one and half hour group session, once a week for six months to aid in preventing any relapse.

In the third phase, clients are encouraged to attend various narcotics/alcoholics anonymous group meetings to gain support.

“Overall we can equip a client with all the necessary relapse prevention but if they do not do the necessary maintenance they can relapse. The maintenance has nothing to do with drinking a pill. It is about going to the various anonymous meetings and keeping in touch with their group and following all the protocols taught.”

Noting that addiction is now categorized as a chronic disease, Prince-Young said, “There is no cure, there is treatment and therapy. The moment you leave rehab and you do not continue with the protocols you were taught or encouraged to continue, you may relapse. My husband never relapsed because he followed the protocols. He accepted that he had a problem and he was proud to know he could give back. It never mattered what time you called him. He would answer that phone.”

And while she is not Mr Young, Prince-Young said, “People call me at any time. Even though we have office hours, it is never about the time. Even though Mr Young is not there, I like keeping his legacy alive. When you see a person come at their lowest point and after a month or two you start to see the transformation, it is uplifting. It brings me back to Clarence’s last words, ‘I didn’t need you to leave your job because I know you love what you do at Marian but I want you to keep the doors open because I know that there are many sick and suffering who would need help.’ If I were to close the door to Phoenix, it would affect that healing process. From October 2017 to today the number of persons who came into Phoenix for the first time has exceeded 150. When you look back at those number, I ask, ‘Had I closed the doors where else could they have gone?’ The satisfaction now comes when you see those persons reintegrated back into society. They are part of the nation building process, holding good jobs [or] their own little businesses. Families have reunited and relationships rebuilt. When they are using substances they may lose their wives and children and loved ones because they can’t have them in their home. Addiction breaks up families. I can speak from experience.”

Young was very unique in what he did, she said. “I just try to make sure that what he put down on the ground is built on and the values he put in place are kept. When a client says ‘Oh Mrs Young is here’, I say ‘but Mr Young is not here’. When we have very challenging clients. I tell them they come to Phoenix at a very nice time. Your encounter with Mr Young would have been different. He was rigid.” Young had a late diagnosis of liver cancer.