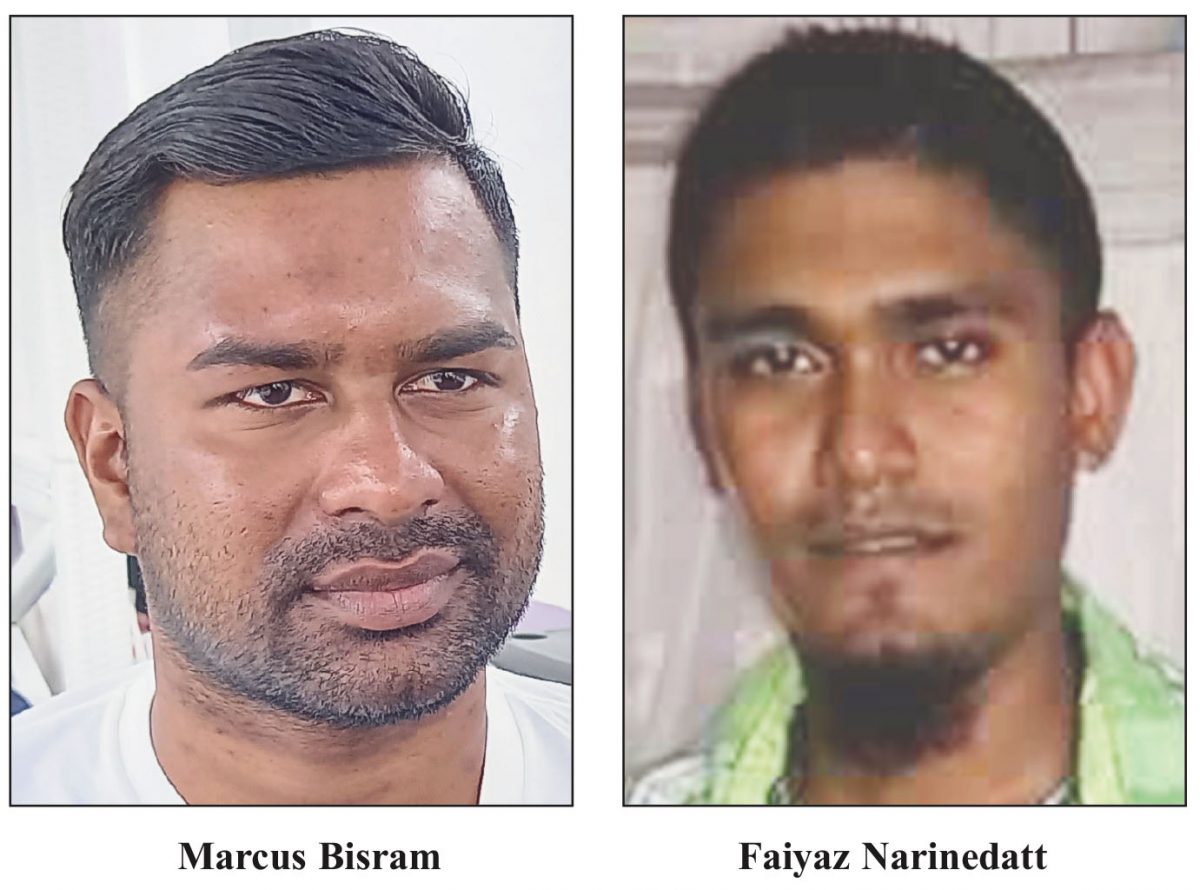

Unless the Director of Public Prosecutions (DPP) can present “fresh evidence” against him, Marcus Bisram will not be prosecuted for the 2016 murder of Berbice carpenter Faiyaz Narinedatt that the police said he had ordered.

His reprieve follows a unanimous ruling in his favour yesterday by the Caribbean Court of Justice (CCJ) voiding Section 72 of the Criminal Law (Procedure) Act, which empowers the DPP to order the committal of a murder accused for trial even though a magistrate has found no prima facie evidence to so do.

“A law which renders the magistrate’s professional decision-making subject to the dictates of another official cuts straight through Article 122A [of the Constitution] and must be declared void to the extent of its inconsistency with that article,” the CCJ said.

Noting that striking down the section would, however, create a gap in the criminal procedure and uncertainty as to when it would be closed, the Court has modified the offending section.

In March of 2020, Bisram had been discharged of murder following the conclusion of a preliminary inquiry (PI) into the charge against him. But he was soon after re-arrested after DPP Shalimar Ali-Hack invoked her powers under Section 72 and ordered the presiding magistrate to commit him to face trial before a judge and jury.

He, however, later challenge the DPP’s directive, arguing that Section 72 was unconstitutional in view of Article 122 A (1) of the Constitution by which it is trumped, because of its supremacy over other laws.

Article 122 A provides, “all Courts and all persons presiding over the courts shall exercise their functions independently of the control and direction of any other person or authority; and shall be free and independent from political, executive and any other form of direction and control.”

‘Failure’

High Court Judge Simone Morris-Ramlall had quashed the DPP’s order but that decision was then overturned by the Guyana Court of Appeal, which later affirmed the directive that Bisram face trial.

Allowing Bisram’s appeal and ruling in his favour, however, the CCJ—Guyana’s final appellate court—declared among other things that the DPP had not even correctly followed the law as prescribed in the offending section by which she was empowered.

President of the CCJ, Justice Adrian Sunders, who read the ruling, said Section 72 required the DPP to first receive the depositions and other material before forming an opinion therefrom that a prima facie case had been made out, as a prerequisite to directing the magistrate to reopen the PI and giving the accused an opportunity to make a statement or call witnesses.

The CCJ said that what it found, however, was that the DPP had made up her mind that the PI should be re-opened with a view to committing the accused, before receiving the depositions, while noting that in so doing she failed to follow the carefully crafted procedural steps of Section 72 “which embody substantive principles of fundamental fairness and natural justice conducive to the goal of a fair hearing.”

“This failure rendered the subsequent acts of both the DPP and the magistrate susceptible to being declared a nullity,” the Court found.

The final appellate court then went on to hold that a law which renders the magistrate’s professional decision-making subject to the dictates of another official cuts straight through Article 122 A and must be declared void to the extent of its inconsistency with that article.

Justice Saunders said that in the instant case, Article 152 of the Constitution—the savings provision—could not apply as it only relates to inconsistency with fundamental rights falling between Articles 138 and 149.

On the question whether Section 72, as an existing law, was saved and immunised from being held to be in contravention of Article 144, the Court re-affirmed the “modification first” approach.

Against this background it held that the savings and modification clauses should be interpreted together so that existing laws should be first suitably modified before being applied.

This approach, Justice Saunders said, allows courts to promote fundamental rights and freedoms by permitting them, ‘to identify an inconsistency between an existing law and the fundamental rights in the Constitution and to modify the inconsistency out of existence.’

The CCJ in affirming the decision of the High Court, said it agreed with Justice Morris-Ramlall that even if Section 72 were constitutional, the DPP’s directive to the magistrate “must be declared a nullity.”

The Court thus agreed with the trial judge that everything that followed the issuance of the DPP’s directive must be quashed.

The Court said it also found that it would be unjust, in all of the circumstances for Bisram to be made to answer any charge of murder in this case on the same evidence as was presented to the magistrate.

The apex court was clear in pointing out, however, that because Bisram, “at least in terms of the law, was never placed in jeopardy, nothing prevents the DPP from having him re-arrested and charged again if fresh evidence was obtained linking him to the alleged murder.”

Modified pending amendment

Regarding Section 72, the CCJ said that simply striking it down would leave a substantial gap in the criminal procedure, without any certainty as to when that gap will be closed.

Thus, it said that until the National Assembly addresses the matter, “Section 72 should be modified to provide that a DPP, who is for good reason disappointed with the decision of a magistrate to discharge an accused person, may place before a judge of the Supreme Court the depositions and other material that were before the magistrate on an ex parte application for the discharged accused to be arrested and committed if the judge is of the view that the material justifies such a course of action.”

In all the circumstances, the Court allowed the appeal and restored the magistrate’s decision discharging Bisram.

On a request from Bisram’s attorney Darshan Ramdhani, QC, the Court also ordered that his passport be returned to him forthwith.

The lawyer attempted to push further for orders that his client’s name be removed from watch lists at the various ports of exit, but the Court denied this request, stating that those were matters for executive consideration and into which it would not get involved.

Unable to arrive on an agreement as to costs, lawyers for Bisram and for the State have been given until Friday to agree on a sum, failing which they were ordered to make written submissions to the Court on the issue by next week Friday.

In addition to Justice Saunders, the appeal was heard by the Full Bench including Justices Jacob Wit, Winston Anderson, Maureen Rajnauth-Lee, Denys Barrow, Andrew Burgess and Peter Jamadar.

The hearing of the appeal had seen a heated debate between the DPP and Ramdhani, who maintained that Section 72 interfered with the independence of the judiciary as provided for in Article 122.

He had submitted that Section 72 was on a “collision course” with the Constitution and for that reason ought to be modified or repealed.

Ali-Hack, however, disagreed, advancing that the exercise of her powers under Section 72 was not only lawful, but reasonable, and embraced the ruling of the local appellate court in that regard.

Bisram had been extradited from the United States to face the capital charge. It had been alleged that between October 31, and November 1, 2016, at Number 70 Village, Corentyne, he counselled, procured and commanded Harri Paul Parsram, Radesh Motie, Niran Yacoob, Diodath Datt and Orlando Dickie to murder Narinedatt.

These five accused are currently on remand awaiting the commencement of their trial before the High Court.

Following the ruling of the Guyana Court of Appeal, the way had been paved for Bisram to be taken back into custody to await trial.

He had, however, successfully petitioned the CCJ for a stay of the judgment of the local appellate court.

In addition to Ramdhani, Bisram was represented by a battery of attorneys including Arudranauth Gossai, Sanjeev Datadin and Dexter Todd.