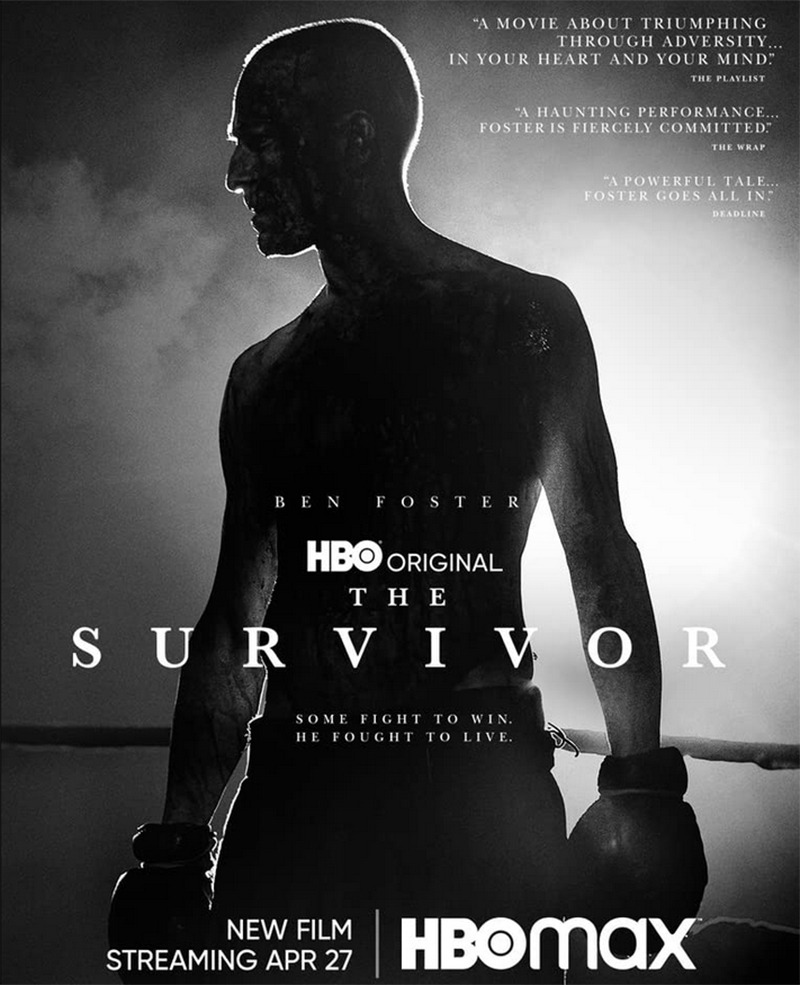

Barry Levinson’s upcoming “The Survivor” finds itself juggling dual timelines for a large part of its running time. In one version, in black-and-white, we find Hertzko Haft, a young Polish man who survives the brutality of Jaworzno by boxing fellow inmates for the entertainment of the Nazi officers. In the other, we find Haft (now Harry) older, tougher, sadder, and still boxing to survive, albeit in the US and professionally. He is hoping that if he finds success, his fame will allow him to reconnect with wartime girlfriend, whom he desperately hopes is still alive. Both versions of Haft are played by Ben Foster, in different modes of physicality – first, as a young ball of nervous anxiety and defiance, then a wearier manifestation of guilt and leaden unease. In some ways, Levinson’s direction, with a very earnest script from Justine Juel Gillmer, does a fair job at explaining why the duelling timelines find themselves intersecting in nonlinear ways. Even though we find ourselves grounded in post-war America, Harry’s PTSD and misplaced guilt linger and the horrors of the past keep bleeding into his present at the most inopportune times. In other ways, though, presenting the horrors of the past through the multiple interruptions of the timelines ends up leading to a recurring issue in “The Survivor,” which for all its tenacity occasionally feels unwilling to confront the most complex emotions and implications of its story.

It makes sense that “The Survivor” finds itself caught between timelines with an almost precious inclination to give us as much information as it can. Levinson’s film is based on the real-life story of Haft’s time as a Jaworzno prisoner and his subsequent recovery, and although the genericity of its title might seem to eclipse the specificity of this gruelling story, it nods to an important quality of Haft that defines much of Foster’s performance. Foster has long been one of the better actors of his generation who has seemed to exist below the radar. Even if “The Survivor” is not near his best film, its firm devotion to giving him tools to show his range makes it feel like an extended actor’s reel for what he can do. This might sound like an odd way to describe a Holocaust drama with such potent intentions at uncovering horrific truths of the past, but “The Survivor” often finds itself in a situation where its reach exceeds its grasp.

The Jaworzno timeline sets up what might seem like a “show-don’t-tell” response to history. Haft’s German-officer handler, played by Billy Magnussen, provides a strong line of conflict in those scenes, emphasising the dichotomy between two young men of similar ages, and even vaguely similar appearances with very different fates but there is little in those Jaworzno scenes that aren’t clearly communicated in the post-war scenes where Foster appears, physically transformed into what seems like a new man. The version of the story in that timeline sets up a psychological excavation of a man trying to simultaneously indict himself and find atonement for what he sees as his guilt in not saving his fellow-inmates in the war. Editor Douglas Crise makes the most of the boxing matches in both timelines, with some effective cuts to build momentum. But even as the actual flashbacks to Jaworzno maps on specifically what the reasons for that guilt looks like, the interruptions from the past leave large sections of the “The Survivor” feeling like it approaches something seismic, complex and complicated only to interrupt any real exploration of those contexts with a too literal attempt at over-explanation to us.

The penchant for over-literalisation is not uncommon in films of this type. It is as if Levinson and Gillmer recognise the weightiness of their subject and pour out all that they can into the film. The choice to present the moments in the concentration camp in black-and-white is clear, but I’m less sure if the George Steel’s cinematography is doing more than tastefully rendering the past, and doing the heavy excavation work the film needs. The literalisation makes for a disjointed narrative experience that becomes, in a way, apropos for Haft’s own story. The tighter version of the film, focusing on Harry’s PTSD and his increasingly despairing worldview, doesn’t seem within the range of possibility and leaves in it’s a wake this version of “The Survivor” which often feels like it’s uncertain what its central narrative arc is. It is Foster who gives a performance of heroic proportions, who bends the film to his film turning moments that don’t always feel propulsive into an actual dramatic arc that gives the film its energy in the final third which jumps a few more decades into Haft’s future. Even if “The Survivor” doesn’t have enough faith in its present-day sequences where a cast of excellent performers orbit Ben Foster in excellent turns, it presents the intersecting fates of those affected by WWII with enough care that the occasional disjointedness ends up working in its way, and with the final switch in timeline the last bit of the story settles into a surprisingly tender meditation on grief that stirs emotions in the most unusual way.

What “The Survivor” lacks throughout is an incisive point-of-view on what living with trauma means for the survivors and those around them. What little context we can extract, comes from Foster and late from Vicky Krieps as his wife. Both of them find themselves haunted by the life, and love, of the younger Haft who lives each post-war moment bound to the past. Levinson feels unwilling to really examine the wreckage of trauma completely, even if brief moments (an outburst at a journalist, a few taut scenes with his son, and a final reunion at the film’s end that jolts for its effect) attempt the incisiveness that’s more muddled elsewhere. Like many historical atrocities, it’s likely that we are fated to many more films about the Holocaust which feel increasingly relevant as the contemporary world experiences its own version of socio-political unease. “The Survivor”, then, is only one in a long line of past and future films that are likely to engage with Jaworzno. One could imagine variations on it that coalesce in a more effective way, but Foster’s performance feels so indelible that it feels good enough to stand above the fray.

The Survivor begins streaming on HBO Max on April 27 to coincide with Yom Hazikaron (Holocaust Remembrance Day)