“He was not of an age but for all time.”

“He was not of an age but for all time.”

(Ben Jonson, 1616)

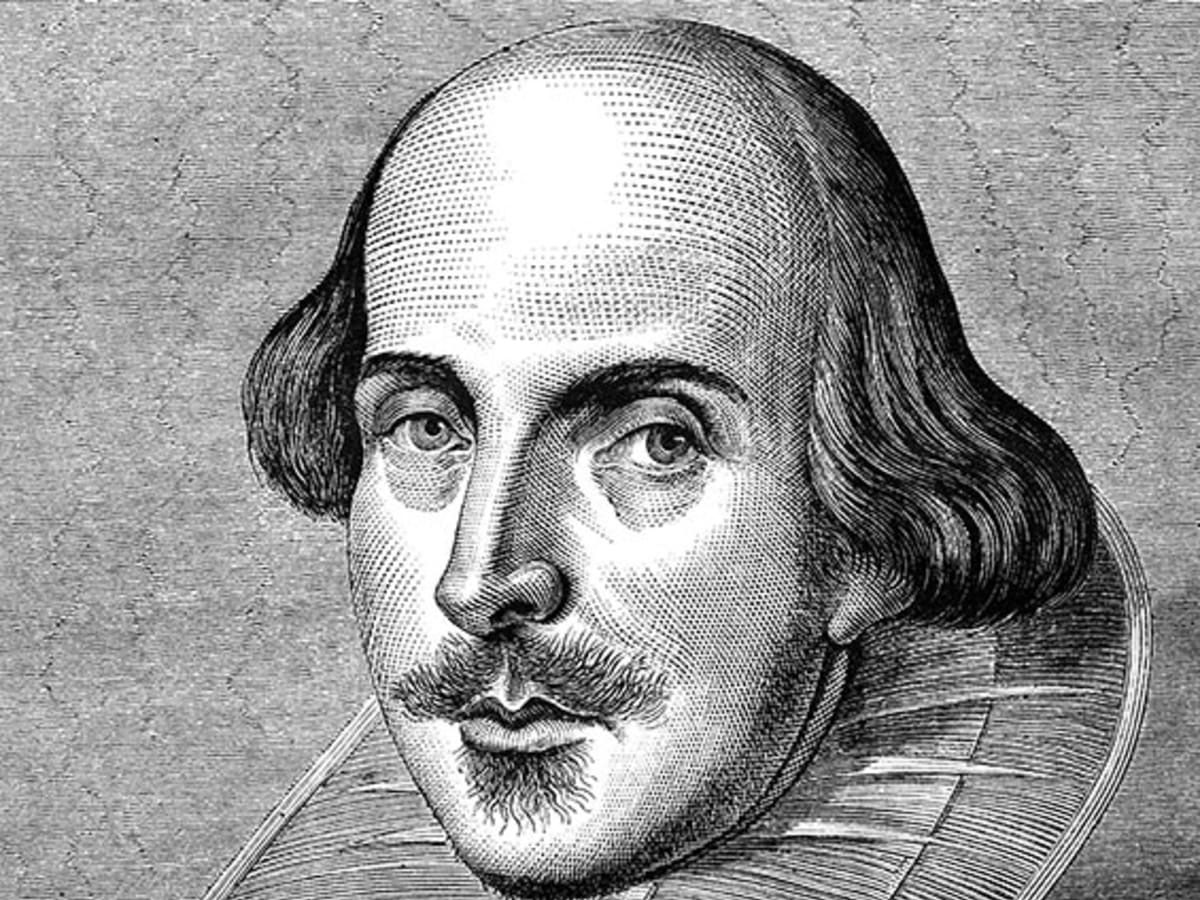

This weekend the world celebrates the birthday of William Shakespeare (April 23, 1564 – April 23, 1616), highly distinguished as the greatest playwright and poet known to the English language and the world.

Shakespeare was born in the town of Stratford, through which flows the River Avon in Warwickshire, England. Stratford is now a thriving urban centre, with an atmosphere ranging from elegant, regal and unhurried swans gliding on the river to the cluster of theatres on the central strip nearby, and a bustling invasion of thousands of tourists.

The birthplace of “the Bard of Avon”, as well as the metropolis of London, and indeed much of the rest of the world, usually explodes with energy in the celebration of the anniversary of his birth. Following a shutdown because of the Coronavirus in 2020 and 2021, all the excitement returned this weekend, with events that started on Friday April 22 and end today, Sunday April 24. This includes special programmes by the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) both at its home in the Swan Theatre, Stratford, and in London.

But why all this fuss over an Englishman who trod the boards all of 400 years ago? There is post-colonial and Caribbean thought which argues that he is no longer relevant, and is a colonial fossil on the canon of literature in this part of the modern world. Some have removed him from the study of literature in English today. But there is a counter-argument that supports his continued relevance and importance.

Why celebrate Shakespeare? Perhaps the greatest reason was advanced by one of his famous rivals and contemporaries, foremost Elizabethan poet-playwright Ben Jonson, who was known to have repeatedly criticised him. Jonson had summed him up as “a man of small Latine and lesse Greeke”. But Jonson was still able to recognise greatness as he wrote in 1616 that Shakespeare “was not of an age but for all time”; an objective and telling testimony.

After Bob Dylan accepted his Nobel Prize in 2017, he wrote that when Shakespeare worked in the theatre, he must have been primarily concerned with managing his actors, stage productions and sale of tickets and surely did not spend time wondering if he was producing “literature”. Yet time has proven him a truly memorable producer of literature.

Time and space will not permit an expansion on the reasons for celebrating Shakespeare as great and relevant, but there is overwhelming evidence in support of this and of the indelible mark he made; there is still material of substantial worth that speaks to a modern society after 400 years. His volumes are very instructive, with themes and arguments in favour of the whole of humanity, and justice for all.

There are plays with post-colonial arguments even so long before post-colonialism, and which treat with conquest, usurpation and even slavery. This includes the creation of a treatise against imperialism found in The Tempest, in Caliban and the abused woman Sycorax. This play, and others such as Titus Andronicus, or Cymbelline, or Pericles or The Winters Tale, touch on forms of slavery and contain feminist arguments against abuse of women. To those add female strength and triumph as in The Merchant of Venice, which also contains resistance to racism as in Othello and Titus Andronicus, with their treatment of the “Other” and the “subaltern” as articulated by modern twentieth century critics Edward Said and Gayatri Spivak.

There are several other plays with theses against usurpation and conquest, burning issues which the world confronts even now in the invasion of Ukraine by Russia. Shakespeare’s works treat governance, republicanism, the monarchy and kingship, republicanism, loyalty and deception, all mixed and covered in Julius Caesar, or Henry IV. There are questions of patriarchy, megalomania, corruption and murder, embroiled in such plays as Richard III. Above all, there is the eternal theme of love, the course of which “never did run smooth”, spread over comedies like A Midsummer Night’s Dream and Twelfth Night or tragedies such as Romeo and Juliet or Antony and Cleopatra.

Shakespeare may be considered great because he was the best in his time but also transcended his time. He did predict in his Sonnets that his lines would be immortal and conquer time. Quotes from his writings have made permanent contributions to English language and sayings in everyday use. The most remembered and identified line in any drama is the famous “To be or not to be” from Hamlet. Ordinary sayings like “all that glisters is not gold” came from The Merchant of Venice, and “some were born great, others achieved greatness, some have greatness thrust upon them” is found in Twelfth Night.

Shakespeare was a product of the Elizabethan Era (the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, 1558 – 1603), which may be considered the greatest age in the development of English !literature and drama. Several very important factors contributed to that and Shakespeare was consistently involved in most of those that coincided with his career. When Elizabeth banned religious drama around 1558, playwrights were forced to find other subjects if they were to survive. Not only did they survive, but they created a new wealth of drama that covered several other areas and enriched the theatre of the time. Much was imported from Italy; and both poetry and drama drew extensively from the Renaissance.

The Renaissance was the rediscovery of the Classics, lost throughout the Middle Ages. This was a vast reservoir of stories, Greek and Roman mythology, poetry, drama, art and philosophy, as well as forms of the theatre – the tragedy and the comedy. Additionally, there was a growth in the practice of patronage. Elizabeth herself was a leading patron, and along with many noblemen provided sponsorship for theatre companies. Related to this was the rise of a number of theatre companies to add to the life of drama at the time. Another crucial factor was that permanent buildings were erected for the first time in British theatre. Before that companies were travelling and performing at several different convenient locations, including the residences of their patrons. But then, the audience for theatre expanded to include the local people once again, and the building of theatres added to that. This began with the Red Lion in 1567. It was not surprising that the era gave rise to the emergence of several outstanding poets and dramatists.

Shakespeare was among them. Moreover his presence was one of the reasons for the greatness of the age. He was the best of them as acknowledged by his contemporaries. He was successful and came up through the ranks as an actor and earned his place from ‘trodding the boards’ and drawing on his exceptional talents. He was a leading playwright, director, producer, manager, and owner of a theatre and of a company of men. His company was the favourite of both Queen Elizabeth and King James I who succeeded her. He earned wealth from theatre. Additionally, while his contemporaries would excel at one genre of play or sometimes two, Shakespeare was successful in four or five different types. He wrote tragedies, comedies, romances as well as historical, Roman, and problem plays. He was innovative, and made some forms of poetry and drama his own: Shakespearean comedy, Shakespearean tragedy and the Shakespearean sonnet.

Shakespeare has indeed been established as extraordinarily great by all measures, both by Elizabethan standards and modern criteria, by measures both materialistic and artistic and by standards both professional and academic. He was in the habit of describing his poetry as “eternal lines” that “in black ink” shall “still shine bright” after all else is gone, and will live “so long as men shall live and eyes can see”. His words proved prophetic.