By Nigel Westmaas

In November 1916, the British Guiana East Indian Association (BGEIA) was established in New Amsterdam. At this meeting, Joseph Ruhomon moved that the Society be called “The British Guiana East Indian Association.” This was unanimously carried. Joseph Alexander Luckhoo, (who as Financial Representative for the South East Essequibo became the first Indian Guyanese to win a seat in the colonial legislature in October 1916), after pronouncing in favour of the idea of the Association, called on Ruhomon, civil servant, journalist and Indian rights activist, to outline the aims and objects of the society. These included, inter alia, protecting the general “interests of East Indians and to obtain redress for them in established cases of grievances”; establishing a scheme for “settling time expired East Indian immigrants on the land under conditions that would ensure to the settlers the best possible results”; amend the colony’s constitution so that Indians could “write their own languages and with the necessary qualifications, may be enabled to exercise the franchise”; advocate and promote “by all possible and legitimate means, the intellectual, moral, social, economical, political and general public interests and welfare of the East Indian Community at large”; and to “promote among East Indians fellowship and social converse and interchange of thoughts and ideas by means of public sports, entertainments, lectures and conventions”.

In 1917 the Association launched the Indian Opinion, described as a newspaper that would report and present the views of the Association. It appears that the newspaper had lapsed publication for a time; in 1920 there were calls for its resuscitation, including consideration of the acquisition of a printing press (Indian Opinion was in existence, off and on, as late as 1946).

BGEIA ROOTS

During the course of the introductions and formal presentations, the organisers said attempts had been made to launch an association of its type since 1892. Berbice appears to have been a hotbed of ideas about forming an Indian association in the colony. For instance, the British Guiana East Indian Institute was reported as being “created in Berbice in 1892.” A Guyanese newspaper also claimed the association was conceived by Ruhomon (intellectual and journalist) in 1895 in New Amsterdam and supported by the Wesleyan minister HVP Bronkhurst.

The Rose Hall disturbances (more often described as a riot) of Indian indentured labourers in 1913, one of the most violent in the country’s history with the killing of 15 sugar workers, was widely reported on in the formal press and by extension a matter of public discussion and discontent with the colonial system. There were other issues of concern. Although there was an Indian mayor in New Amsterdam, there were no positions open to Indians on the Court of Policy up to that time. A 1915 Commission of Inquiry had also found that the position of free immigrants had “grown in numbers, wealth and influence”. But in spite of this, less than “six percent of the Indian population were on the voters’ list.” It concluded that “there need be no doubt that when the interest of the Indian community indicates the need for political activity they will avail themselves more fully of the rights which they enjoy.”

There were many challenges in the period. Indian Guyanese and their middle class representatives stridently opposed the Recall movement for Governor Walter Egerton, which was a hot button issue in 1916 and pitted Indian Guyanese against African Guyanese and other interests, the colonial government having previously insisted on limitations to constitutional reform (Crown colony government) as a precondition for a proposed construction of a railway to Brazil. The Recall was initiated by and supported by African, Portuguese and Coloured members of the Combined Court including JP Santos, AB Brown, Francis Dias, Nelson Cannon and JM Rohlehr. Thomas Flood (Indian Guyanese sportsman and businessman who died in December 1920) and other Indian Guyanese called a town hall meeting to decry the “disloyalty” toward the Governor and, to applause, the meeting called on everyone to “stand shoulder to shoulder in support of the British flag…and not to hinder the representative of the King in the government of this colony.” Ultimately, the Recall move against the governor was unsuccessful.

1919 BGEIA REDUX

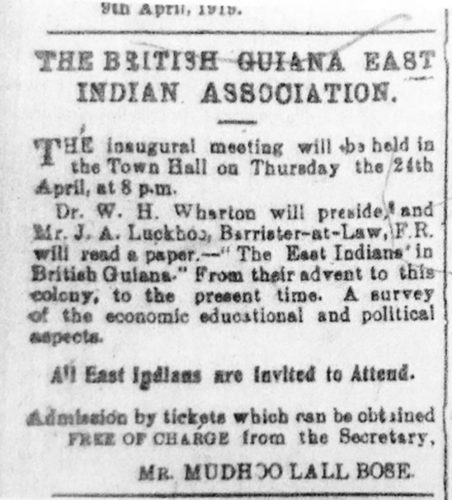

The first meeting of the newly recalibrated BGEIA occurred at the Town Hall in Georgetown on the 24th April 1919 before a large attendance. By this time, the Berbice Association had merged with its Demerara counterpart to become a single entity. Luckhoo was elected President. Sir Wilfred Collet, the governor of British Guiana was invited and attended the inaugural meeting, as was common with organisation launches. Also present and delivering a violin solo and the British national anthem was an African Guyanese, George Carrington.

Months before the formal launch of the BGEIA in 1919, the Indian community had by resolution assented to the proposal to form the association and office bearers were elected. These included Thomas Flood and Dr WH Wharton (Indian Guyanese doctor of medicine), Honorary presidents; JA Luckhoo, President; GT Ramdeholl and JA Viapree, vice-presidents; Mudhoo Lall Bhose, secretary; Peter Ruhoman, assistant secretary; and Manraj, treasurer. The inaugural Georgetown meeting of the BGEIA included a main address by Luckhoo, who read a paper, “The East Indians in British Guiana; from their advent to the colony to the present time; being a survey of the economic, educational and political aspects,” which included a call for advocacy over a number of issues of concern to the Indian population including Indian education, the franchise, land settlement issues, voluntary immigration from India, and encouraging “interest in matters political as affecting the welfare of East Indians.” The chairman, Dr Wharton stated he was pleased to see “such a large gathering of Indians and other fellow colonists present…which showed that good fellowship existed between the Indians and other races in the colony.” Wharton also added: “it was first thought that the meeting should be a racial one but thanks to the good judgement and common sense displayed by the committee that idea was abandoned.”

The BGEIA was in the main middle class and led by intellectuals, businessmen and professionals whose social status and political outlook were generally conservative. Or as Mohan Ragbeer (2011) put it, “many BGEIA members and officials had assumed most, if not all the norms of Victoriana still dominant in Guianese polite society.”

COLONISATION SCHEME DISSENT

The controversial Colonisation scheme, leading to disagreement between the colony’s Indian and African citizens and leaderships originated in 1919. One underlying concern of the black community was the 1911 Guyana census, which for the first time gave Indians a numerical advantage in the colony. Advanced mainly by Joseph Luckhoo and the Attorney-General JJ Nunan (both travelled widely to garner support for the scheme) the Colonisation Scheme created ripples in the community. As Clem Seecharan (2011) notes, the issue “precipitated an amazing articulation of local opinion pertaining to the character of the economy…the perennial hazard of drainage and irrigation, the potential source of immigrants and the fundamental question of ‘ethnic balance’ in British Guiana.” Given the ‘ethnic balance’ dilemma, Seecharan posited that the Scheme “exacerbated African fears and strengthened their resolve to resist not only the idea of an Indian colony but the whole Colonisation scheme.” But opposition also emerged inside the BGEIA and Indian National Congress leader Mahatma Gandhi (whom the Luckhoo group met with) was quoted as stating that he “was not in favour of a single person leaving India; but if he secured official guarantees of continued commercial, legal and political equality in British Guiana he would not oppose the scheme publicly.” In general, fearing a concealed form of indenture the Indian government was opposed to the Scheme. The result was an eventual BGEIA resolution dissociating the body from the Colonisation scheme although not, from all indications, of the broad idea of an “Indian colony.” A dissenting voice, JA Veerasawmy was quoted as stating: “the idea of aiming at an Indian colony only tends to create unpleasant feelings between East Indians and other races in the colony.”

Later, in 1928, the Colonisation scheme was reactivated, and there was discussion on its possibility and potential in the Legislative Council in 1929. But like its 1919 predecessor, it did not materialize. Other “colonisation schemes” would follow and all were aborted, including the Turkish Assyrian scheme for British Guiana in 1934, and the Jewish Colonisation scheme of 1938-1939, which proposed the settlement of Jewish refugees in the Rupununi. The Second World War, among other issues, interrupted these British colonial plans.

In 1924 the BGEIA and its then President Francis Kawall (described as “vehemently opposed” to the Colonisation scheme) were very active in the labour protests, along with Hubert Critchlow and the British Guiana Labour Union (BGLU) that eventuated in the killing of workers at Ruimveldt.

By 1929 the BGEIA was already at the forefront of activity in the community. In December of that year, for instance, it made representation, together with Critchlow’s BGLU to the Colonial Secretary for Universal Adult Suffrage in the colony. The BGEIA also campaigned for a “printing press to publish a newsletter in Hindi, Urdu, and English for the benefit of the East Indian community.” One prominent and influential member if the BGEIA was the Hindu leader Dr. Jung Bahadur Singh (known for his medical support for Indian immigrants as a ship doctor) who served as President of the organisation for a record seven times.

But there were also internal contradictions in the Association inclusive of squabbles over leadership and rules. This came to a head in 1931 with a public spat over which candidate was rightfully qualified to be President of the Association, as exemplified by a deadlock between AE Seeram and Deonarine Singh, with the latter eventually prevailing.

In May 1937, at its annual Assembly, the BGEIA put forward resolutions, including the request for adequate Indian representation on Public Boards and education issues. The BGEIA further campaigned for a literacy programme for Indian children. The Daily Chronicle reported that “illiteracy among East Indian girls has been aptly described as a colonial danger.”

As with other organisations and individuals, in 1939 the BGEIA submitted evidence to the Moyne Commission (the Lord Moyne commission visited the Caribbean in the wake of the labour protests and rebellions across the region), with the broad desire to “preserve racial identity (of Indians) and religious precepts.”

One encounter between CR Jacob and the Moyne Commission on behalf of the “whole Indian community” went thus:

Q: Do the views you have set forward in this memorandum, that you have been good enough to let us have, represent the views of the whole Indian community?

CR Jacob: We would say 95 per cent…This Association had been in existence for 20 years and it has the confidence of 95 percent of the community, Christians, Hindoos, Muslims and we are so composed.

This of course was an exaggeration. With a population of 130,000 Indians in the colony, only about five hundred were “financial contributing members of the BGEIA” in 1938. But while the BGEIA might not have had the support of 95% of the Indian community, there was overlapping membership in the labour union, Man Power Citizens Association (MPCA) launched in 1937. The BGEIA generally supported the Indian working class and there were attempts to attract a rural base.

Faria Nasruddin (2020) characterised the collective efforts of the BGEIA as a “political imaginary” intended to “create a homogenous cultural community” that “proposed a new model of citizenship in the colony that resisted creolization.” Nasruddin also emphasized the middle-class orientation of the BGEIA: “when the BGEIA claimed to represent all East Indians in British Guiana, they actually muddled the boundaries between speaking on behalf of and speaking for. The middle class urban elite aimed to further their own place in mainstream society and legitimize their own place in the face of colonial power….ultimately supporting the colonial authority’s system.” In this endeavour the Association underscored its middle class orientation, along similar lines as the rival ethnic organisation, the Negro Progress Convention (established in 1922). Nonetheless, the two groups held distinctly different views on many issues but maintained a mutual cordiality, especially in the 1930s. However, African and Indian interests in Guyana between 1928 and 1950 largely came from the middle class led League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) and the BGEIA.

In 1944, the membership of the BGEIA stood at around 800. New faces who would become prominent in their own right were members of the association including CR Jacobs and Ayube Edun. Among the new faces by 1947 was Dr Cheddi Jagan, who joined the BGEIA and was Secretary for a period but reportedly left within the year, disappointed with the Association’s ideology and trajectory.

The BGEIA was also quite active, together with a number of organisations, labour and political, as part of the general agitation in support of the victims of the 1948 Enmore shootings of Indian sugar workers.

In January 1966, before independence, the BGEIA was still active. At its annual general meeting the body voted to send a letter congratulating Indira Gandhi on her election as Prime Minister of India. There was also a discussion on amending the rules of the organisation to allow membership “to non Indians.” There is no indication of whether this ruling was activated but the site of many BGEIA meetings, the British Guiana East Indian Cricket Club, established in 1914, became the Everest Cricket Club. While remaining active for an indeterminate period after independence, the Guyanese East Indian Association was certainly not operating on the same scale and had little of the influence it attracted during the colonial era.