Introduction

Today’s column continues the coverage of my linking of the theoretical analysis; that is Pillars A B completed so far and policy formulation for the sector, to come. It covers 1] a wrap-up of Item 1, via discussing the second of the two existential threats, which I have listed as an indicator/ marker, or data point for shedding light on the current situation in regard to Guyana’s oil and gas sector; and 2] the shares of various cost items in modelled estimates of the country’s offshore crude oil operations over the time period of my analysis – up to the late 2030s

Existential Crisis cont’d

Last week I dealt with the first of two existential threats. That is, my conviction Guyana’s oil and gas sector [and therefore by implication all Guyana]; faces over the time-frame to the late 2030s a potentially dangerous outcome due to the geo-political threat posed by Venezuela’s territorial claim against Guyana. Over the similar time-frame of the analysis, the other such threat is, I believe, an environmental spill on the scale of the BP Deepwater Horizon catastrophe of 2010, costing to date US$65 billion

To be very clear, this other foreseeable existential threat indicator is, in my view, a theoretical possibility because of the offshore upstream location of Guyana’s crude oil and gas operations. Even though highly unlikely this outcome defines the configuration of the emergent petroleum sector of Guyana. Of course, this threat is situated at the local level as it is based on the offshore location of Guyana’s oil operations. This should not therefore, be conflated with the global climate change transition.

In response to the above observations four caveats have been raised. I mention these here in order to underscore the integrity of my claim about the threat and not to promote inadvertently, deception and alarmism, which have been rife in the social and print media. These are evaluated in the next section.

Four caveats to this threat

The four caveats in random order are:

1. Worldwide, Guyana oil tanker spills are covered by the International Conventions on Civil Liability and Compensation Funding under the auspices of the International Maritime Organization (IMO). The regime provides for pollution damage legal assignment and compensation for assessed clean-up 1and remediation. Guyana became the 116th State Party to accede to the 118 Member body as of March 2022

.2. In the literature, it is widely believed that adequate financial provisioning and strong company balance sheets are the best safeguard. As reported in Oil Now, ExxonMobil has said it has a robust Oil Spill Response Plan to cover any eventuality; including shore-based incidents and offshore operations. The size of Exxon Mobil funding for spills is reported to be US$ 2 billion.

3. Readers may recall Guyana has produced a National Oil Spill Plan August 2021. This is subject to annual review. The Civil Defence Commission is the coordinating body responsible for emergency response preparedness, clean up and damage control.. It coordinates with the IMO mentioned at 1 above

4. The fourth caveat is the notion of moral hazard. That is the perverse incentivizing effect towards more risky behaviour that insurance can promote.

While the caveats are noted they cannot secure against the theoretical possibility of an existential environmental catastrophe.

Modelled cost shares

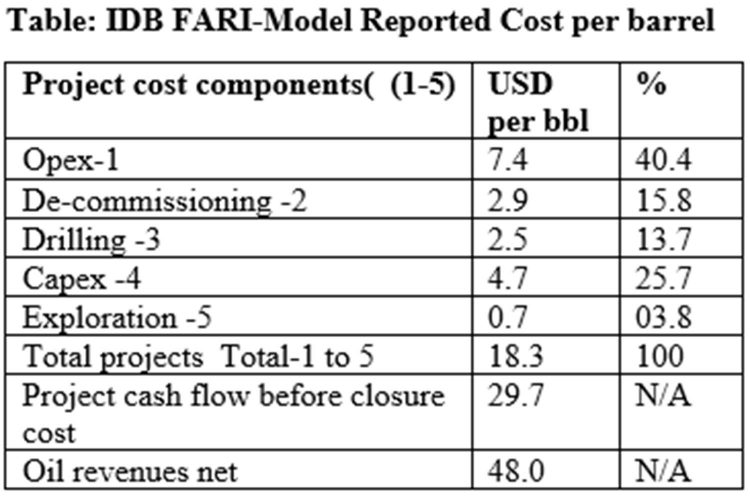

The second indicator of the condition of Guyana’s petroleum sector is the revealed cost shares for the on-schedule five projects to2023/6; Liza 1, Liza 2, Payara, and Projects 4 and 5 to follow. Several estimations have been attempted ranging from stock analyst and energy intelligence firms publishing in Raising Alpha to major firms publishing on their own behalf like Wood Mackenzie and Rystad Energy. Below I highlight the IDBs contribution. The Table below shows is their projected data on 1) the five projects cash flow before the closure or de-commissioning fund 2) net oil revenues from the five projects and 3) their overall and individual items per barrel cost of production.

The data reveal that operational expenses [Opex] is the largest item for the cost of producing a barrel of crude oil. Opex refers to day-to-day operational expenses [wages and salaries, rent, utilities, legal and accounting, general and administration, overheads, R&D, and so on]. These ongoing expenses account for US$7.4 per barrel of crude oil or 40.4 percent of the estimated US$18.3 required to produce that barrel in the model.

Capital expenditures [Capex] at US$4.7 per barrel is the second largest item, accounting for 25.7 percent of the per barrel cost. While Opex is the ongoing short-term expenses, Capex represents longer term significant expenditures directed at improving future performance beyond the current fiscal year [typically. long- term expenses like property, plant, equipment, and other fixed assets]. Together, the model reveals that Opex and Capex combined account for about two-thirds of the cost of producing a barrel of crude oil.

It is of note that, nearly one-sixth of the cost for producing a barrel of crude is devoted to a de-commissioning fund. This belies the noise and nonsense disinformation narrative concerning Guyana’s intended abandonment of its oil producing structures when the reservoirs are depleted. Similarly, the narrative of the endless burden of gargantuan exploration debt comes up against the reality that, exploration debt is projected to account for only 70 cents or 3.8 percent of the per barrel cost on the Stabroek block.

Conclusion

Next week I turn to the next sample indicator of the state of Guyana’s oil and gas sector.