Red Thread’s members are primarily grassroots women, who live daily with various forms of economic and social insecurity. Despite this, over three decades, we have built an organisation that advocates and organises with women, beginning with grassroots women, to cross divides and transform our conditions. Red Thread runs the Cora Belle and Clotil Walcott Self-Help Drop In Centre, which provides support for and advocates with survivors of domestic violence as well as low wage workers (https://redthreadguyana.org/)

Red Thread’s members are primarily grassroots women, who live daily with various forms of economic and social insecurity. Despite this, over three decades, we have built an organisation that advocates and organises with women, beginning with grassroots women, to cross divides and transform our conditions. Red Thread runs the Cora Belle and Clotil Walcott Self-Help Drop In Centre, which provides support for and advocates with survivors of domestic violence as well as low wage workers (https://redthreadguyana.org/)

Starting a few months ago, a group of Indigenous, African and Indian Guyanese women from Regions 3, 4, 5, 7 and 8 have been meeting to talk about oil. We have been learning some basic facts, including: What is a fossil fuel and how is this different from the oil that we extract from vegetables (coconut, corn etc.); why are fossil fuels non-renewable and what does that mean; where and how is the oil stored – under the ground, under the ocean – and how do you get it out; what are the environmental risks?

As always, we ground these teachings in our own experiences. This is why we started our conversations by talking about where we are seeing the effects of the oil economy directly, and that is in the increased cost of living and what it is doing to our household budgets.

Two weeks ago we read an article about Exxon in Guyana that came out on May 12 in a British newspaper, The Guardian. We spent time discussing the words of two fishermen who were interviewed for the article and who spoke about what they believe to be the effects of Exxon drilling on fish catches. The title of the newspaper article, ‘You can’t eat a new road,’ came from a fisherman, Steve Outar, who said he doesn’t want to lay off his 28 crewmen because they have families to feed, but that some of his boats are now spending close to three weeks at sea and still not catching enough.

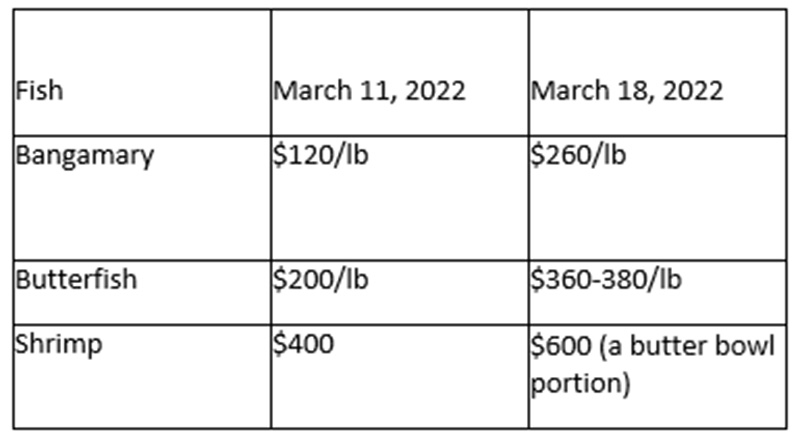

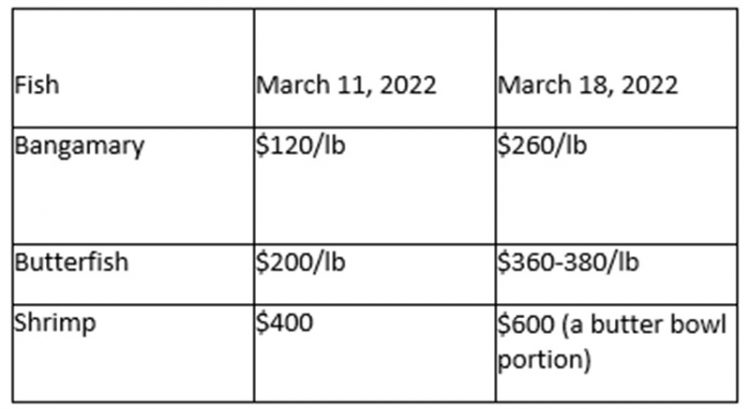

We already know some of this from the weekly household budgets we have been doing, because most of us no longer buy fish, which is now scarce and expensive. Back in March we wrote an article where we showed the changing prices in Vreed-en-Hoop between March 11 and March 18.

After reading that newspaper article, where the most important voices were the voices of the fishermen, we agreed that we would go back home and ask fisherfolk about their own experiences. Last week when we came together, we found similar stories across our communities, from Mahdia and Bartica to West Bank Demerara, from Georgetown to East Coast Demerara to Mahaica-Berbice. Here are some of them.

In Georgetown, the husband of one of the women works part-time at a fish shop where he scrapes and fillets fish. His normal working hours are three days a week. These days, he regularly gets told not to come in because there is not enough fish being supplied to the shop. Up to about three months ago, he and his father would also buy fish on the wharf and go around with a bicycle selling it to households, but they have stopped doing this as supplies are low. In one West Bank Demerara community, the local vendor no longer sells fish because he says it is too expensive for people to buy and he cannot afford to stock it and for it to spoil on him. A woman from another village said the man who would come with a horse cart no longer brings fish since supplies are low, and if she has extra money to buy fish she has to go to Leonora, Parika or Zeeburg (even the vendor who sells at Vreed-en-Hoop and who she would buy from had no fish when she went last week). Women spoke of how scarce shrimp and prawns are, and said the big March tides this year saw no real crab season either.

In Mahdia, we learned that some men who used to work on the coast on deep sea fishing vessels have returned to the area to cut logs as they can no longer find work at sea: ‘fish not running no more, and that’s why they had to come and go at the backdam.’ Saltwater fish is very scarce, for example for two weeks there was little to no supply and when bangamary was available it was selling for $800.00 a pound. Compare this with the price at Meadowbank in Georgetown when bangamary is available, which is $260 a pound. In Bartica the price last week was $500/lb for uncleaned bangamary, and $1000 for four uncleaned fish. In West Coast Berbice, three small bangamary sold for $500, or $1000 for three big and one small fish, while in Stabroek Market four medium sized bangamary sold for $1000.

The Guardian newspaper article had a picture of fishing boats at Liliendaal, and said that fishers are saying that fish and shrimp are being driven away by the vibrations from oil exploration. One of us who lives in Industry went to Liliendaal, and was told that the regular fisherfolk are not really working there anymore because they are not finding fish so they are going elsewhere. In Region Five, we learned that some fisherfolk who would normally go out at Belladrum cannot go there now as a set of mud has come in. They go to other areas, like No. 28 village, but they reported that they have to go out further to sea and even then, they are catching far less fish than before. Women in West Bank Demerara (Region 3) spoke with fishermen as well. One said that he used to spend six days at sea, but is now spending as much as 18 days to a month at sea, and is travelling as much as 20 miles further out to sea. Even with the longer time and distances, he is still not catching enough fish.

We also noted that one of the things we are seeing is increasing numbers of people with lines trying to catch fish in trenches and canals – on Mandela Avenue, Princes Street, Industry, Plaisance, in the rice field canals on the West Bank. We think this is because there is less fish available to buy and it is very expensive, so people are trying to catch their own or do without. We know this firsthand, as we had decided among ourselves to track the price of bangamary because that is the only fish we can afford to buy. The truth is that none of us is able to purchase or eat fish regularly or anymore.

Last week Friday, Demerara Waves carried a story in which Minister of Agriculture Zulfikar Mustapha claimed that it is climate change and not the oil and gas industry that is leading to the decreased supply of fish, and the Minister said that a study by the Food and Agriculture Organisation supported this finding.

This is very different from what we are hearing in our communities, and from what people are saying. In the Guardian newspaper article, a fisherman who was interviewed named George Jagmohan used to have seven fishing boats but is selling them off “one by one since the oil drilling began.” He said that “since the drilling started, the fish have gone. It’s the blasting and vibrations…In another couple of years it will be finished. It never used to happen. People aren’t stupid. I’ve been fishing for 40 years and it’s not been like this before.” Another fisherman, Steve Outar, whose catch is down by as much as 80%, believes that the vibrations caused by oil drilling “are driving the fish and shrimp away.” We do not believe that it is just a coincidence that the fishing industry has gone into the dumps since Exxon Mobil started drilling offshore in Guyana’s waters.

The Guardian journalist spoke with fishermen. As grassroots women, we looked at our budgets, at what we are seeing in our communities, and we also visited fishing areas (some of us actually live there) and spoke with fishermen. Some of us live with people who depend on the sea for their livelihood. These are the people who are making the connections between oil drilling and our environment. So here are our questions to the Honorable Minister of Agriculture Zulfikar Mustapha and to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO):

Can the FAO publicly confirm the Minister’s statement that based on their study, it is climate change and not the oil and gas industry that has caused the current decline in fish catches in Guyana? The FAO has not said anything so far. Does that mean that this is in fact the conclusion of their study?

Is the oil and gas industry not one of the major contributors to climate change anyway?

When was the FAO study done?

Who exactly did the FAO speak to in order to come up with this study that the Government of Guyana is drawing on and which lets the oil and gas industry off the hook? All of the fisherfolk we spoke to are saying differently. How was their knowledge counted? Did the FAO researchers speak to fisherfolk and their families, and if so, how many, over what time period and across which communities in Guyana?

Was the FAO study based on information from the fishing industry that was collected before and after oil production started, so that there is a starting point that allows you to measure changes and decide what has caused the change? And exactly what kinds of information did they collect that would allow them to come to a conclusion where the Minister of Agriculture could confidently say that the oil and gas industry has nothing to do with what we are seeing across Guyana – lower catches, higher prices, people being put out of work in the fishing industry and so much more?

Who feels it knows it. As grassroots women, what we feel and what we know is that communities are making a connection between Exxon drilling and what is happening with our fish. We call on the FAO to release this study so that the public can see for themselves. This is information on a matter that concerns Guyanese people and should be widely and easily available to all of us.