Five years after the final submissions were made in a court action against the Government of Guyana by the Indigenous peoples of the Upper Mazaruni, who are seeking legal recognition of their rights to traditional and ancestral lands, community leaders are still awaiting a ruling.

For 24 years, communities that fall under the Upper Mazaruni District Council (UMDC) have been engaged in a legal battle to reccognise their land rights and now hold the view that the lengthy delay in bringing the matter to a conclusion amounts to a denial of justice.

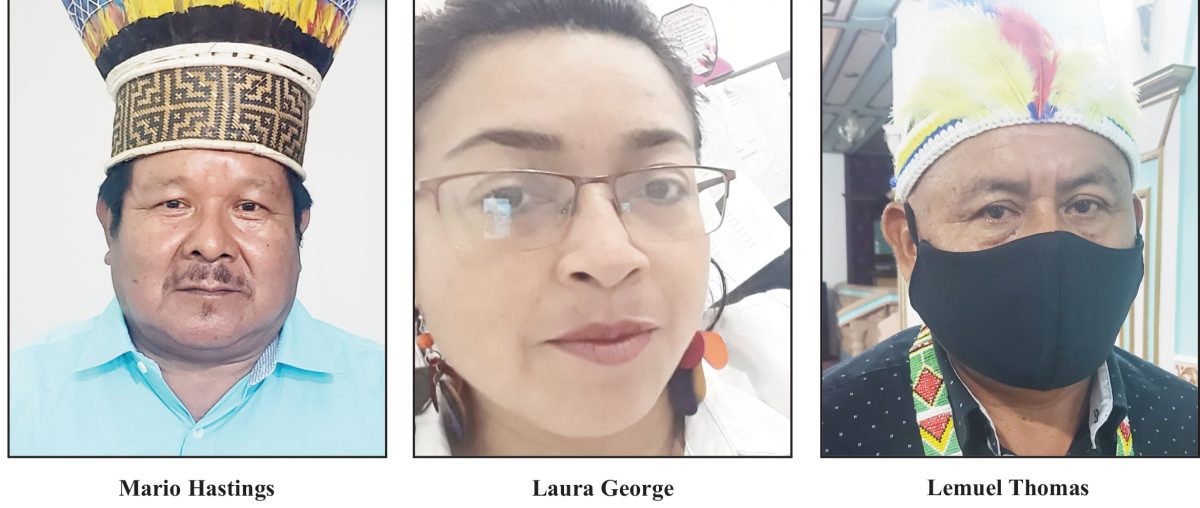

Chairman of the UMDC and Toshao of Kato Mario Hastings told Sunday Stabroek that since the filing of the final arguments in 2017, no substantial reason has been given for the delay in the ruling. They were told that the delay is due to a backlog of cases in the court.

Indigenous People’s activist and native of Phillipai Village Laura George added that the lack of response to the case and the judiciary’s failure to act on speed up the time in which matters are heard, appears to be discriminatory.

“You have court cases where there’s a decision being made quicker that our 24-year issue. Now, if the last submissions were made in 2017, what is it that is keeping the judiciary from making a decision? Why such a long delay for the Akawaio’s and Arekuna?” George questioned.

George reiterated that their fight for recognition is based on the fact that they want it to be determined that they are the real owners of lands, for which mining permits are being given.

“Our rights as indigenous peoples have been violated in so many ways under so many phases of so many mechanisms. Our rights to give our consent to what happens on our lands have been violated over and over by systemic discriminatory practices, and decisions of political administrations. And now this is looking, we’re looking to the judiciary to affect our rights, and it’s not happening yet,” George said, while adding that they are hoping that the court makes their ownership of the land clear.

Deputy Chairman of the UMDC and Toshao of Kamarang Lemuel Thomas added that the land rights is one of the burning issues they were tasked with resolving and a result their villagers are pressing for results.

Thomas said that in the past 24 years many of the original plaintiffs and witnesses have died although many of their family members are still keen to see an outcome.

“This is a struggle of our people and it is sad situation because many pass away never seeing the outcome of these things,” he said.

“Their families who are alive are pressing us and saying they need to see this through…this is a continuous struggle for us and as elected leaders we were given the mandate to fix this,” he added.

Hastings pointed out that past and present governments have given their commitment to resolving indigenous people’s land rights issues but to date that is still to become a reality.

He pointed out that successful governments have fooled them and many are of the view that they should not participate in future elections. Governments’ failure to address these critical issues, he said, have created a lot of doubt and mistrust among their people.

“Governments come and government go and they make commitment to the people but we have been fooled many times… We may have to let our people know it is not worth taking part in elections if this is how past, current or future [governments] are going to treat us,” Hasting underscored.

More harm

The community leaders said that the delay in a ruling on this specific matter should not only be a concern for them but for every Guyanese. They posited that if the judiciary fails one group it fails all and they must stand united to ensure their rights are always respected.

The leaders believe that after the two decades and a half that have elapsed the matter should have already been put to bed rather than being dragged out.

An emotional George said this matter was initiated when she was just a young girl in her village council and recalled being at the meeting where they were informed that taking the decision to go forward might be a lengthy process.

“We didn’t expect it would have taken this long,” she said.

At a press conference last year, Hastings reminded that the decision to go to court was a continuation of the struggle of their foreparents to secure control over the territory for the benefit of future generations. “Archaeological evidence shows that our people have occupied the Mazaruni River basin for over two thousand years. Our homes, cultures and livelihoods depend on our territory. When Guyana gained its independence more than half a century ago and constituted the Amerindian Land Commission to document indigenous lands in the country, our leaders requested to the commission that the six villages in the Upper Mazaruni be granted joint and collective title to our territory. The request was ignored and continues to be so to this day,” he lamented.

With the delays by the judiciary, the UMDC leaders said more harm is being inflicted on their communities through both renewals and issuance of new mining concession permits.

Within the last 24 years, Thomas said, they have witnessed phenomenal environmental changes in their territory and wildlife habitats.

He explained that the Mazaruni River, which many indigenous communities depend on for their source of fresh water has become polluted and creeks and lakes have dried up or in some cases been blocked off by dredges due to mining activities.

According to him, when permits are granted there is no prior consultation with the communities but rather after and in all cases, the operators go to the community asking for community “buy-in.”

“They do not understand that these lands are ours. They see where we live and dwell as what we own but our lands go beyond that… these are our ancestral lands that we survive on by farming and hunting. We are the protectors of these lands… we are better guardians than the LCDS [Low carbon Development Strategy] programme,” he said.

According to Thomas, when operators move into their villages they wipe out anything that is in their way. Expanding on this, the Toshao said many farmers have been forced to relocate and in some cases have not been able to find suitable lands to farm and have to travel further in the jungles to hunt for their food.

He stated that they have seen the fish population declining in the rivers and creeks, the size of the fishes smaller than what he grew up knowing and they a different taste, which he believes is as a result of mining activities in the river.

“The time you spent to catch ten fish few years ago verses now is longer, the fish tastes more like mud now and are smaller… even the colour of the fish is different. So, yeah, we have seen the impacts and it’s all because we haven’t been able to have a say on what goes on, on our lands,” Thomas added.

He added because they have no say on what goes on their lands, they have retreated from fighting for their lands.

“The miners will come and say I have a permit you have to move. There is no say by the indigenous person they have to move out… this is the struggle we continue to face,” he lamented.

On this front, Hastings pointed out that there are signs in the environment to suggest it is not healthy and many of their people have been suffering from skin conditions — mainly rashes – suspected to be caused by the water that they are ingesting and bathing in.

He also stated that there is evidence of deforestation from mining activities.

Thomas further pointed out that in the government’s LCDS there is a proposal for areas to be designated as protected areas, but while this is welcomed, he said it upsets him to know that such proclamation will negatively impact their traditions and livelihoods.

“That will really interrupt our fishing and hunting grounds. We will have to look at new lands but if they give us the power to protect the lands we will be able to take care of it. We have been doing so for generations. We have a better plan than what the LCDs offers because we have been passing down the knowledge of how to care for the environment from generation to generation,” he emphasised.

Hastings added as indigenous leaders it is their wish to see a government that is prepared to stand by them and protect their rights. But he said there appears to be an absence of political will. “The problems are still there and we really feel that a ruling on this matter is very, very important. So that we would know how to move from there onwards,” Hasting stated.

Hasting had said in the Upper Mazaruni they received separate land titles in 1991 but the lands that were given have little to no cultural meaning and large swathes of their traditional land were kept as state property. According to Hastings, this was what led people living in the area to take the case to court seeking a judicial declaration confirming their rights to the land. He noted that although international human rights bodies, such as the United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, have called upon Guyana to legally recognise the lands, territories and resources that indigenous peoples have traditionally owned or occupied, this was not done. He pointed out that the decades-long denial of their land rights violates their constitutional rights as per the constitution of Guyana.

In addition, he said, the delay in a decision blatantly denies their right to access justice, which according to the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights, requires a case to be determined within a reasonable time.